The photo of an antefix (half and half)

Art Matters is the podcast that brings together popular culture and art history, hosted by Ferren Gipson.

Download and subscribe on iTunes, Stitcher or TuneIn

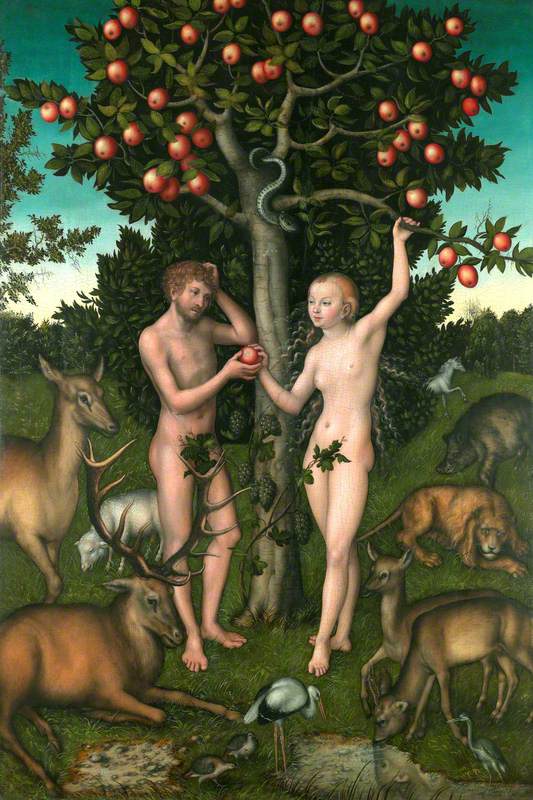

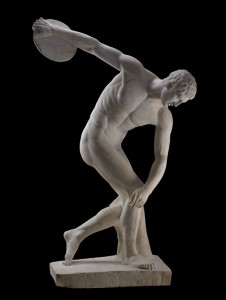

If you're not familiar with polychromy, seeing classical sculptures painted in colour may feel like walking into the scene from The Wizard of Oz when Dorothy steps into the Technicolour dreamworld of Munchkinland. Polychromy is the art of using multiple colours to paint architecture and sculpture.

A painted copy of Caligula

Most likely, if you walk the halls of a museum with classical sculpture, you'll see white marble works dating from the classical period through to today. In reality, these ancient Greek and Roman sculptures were originally painted in bright colours and, while many people aren't aware of this, this knowledge isn't new.

Large polychrome tauroctony relief, from the mithraeum of S. Stefano Rotondo

'Already with the first excavations of sites such as Pompeii, scholars were aware that these artefacts were originally painted,' says Cecilie Brøns, Senior Researcher at the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen. Early excavations in Sicily and the Athenian Acropolis have shed light on polychromy, but somehow it's still not widely reflected in the sculptures we see in museums. It could be that over time we've become so accustomed to seeing white marble sculptures that it's now our aesthetic preference. Even if you look at a film set in ancient Greece, one would expect to see pure white buildings and sculptures.

Historically, sculptures may have been cleaned before being sold or as they entered collections, though this doesn't account for every case of sculptures losing pigmentation. 'The primary reason why these sculptures are white today is the nature of ancient paint,' says Cecilie. Ancient paints were comprised of pigment and a binding medium. While the pigment – which gives a paint its colour – may be inorganic and able to hold up over long periods without decay, the binding agents that helped ancient paints stick were often degradable.

'They were made from egg – maybe egg yolks, for example, or egg whites – milk, or a plant oil, or animal glue,' says Cecilie. 'All of these components are organic, so when they're in the ground for several hundred or even thousands of years, these binding media have dissolved, so the paint has dissolved and disappeared.'

We can determine how some classical sculptures lost their pigment, but at some point it seems to have fallen out of fashion to paint sculptures altogether. More modern marble sculptures, for example, were never painted, even when inspired by Greek and Roman themes and aesthetics. Popular sculptors from the Neoclassical period like Antonio Canova preferred to leave his sculptures unpainted.

Peplos Kore as Athena and Artemis

Finding the colour

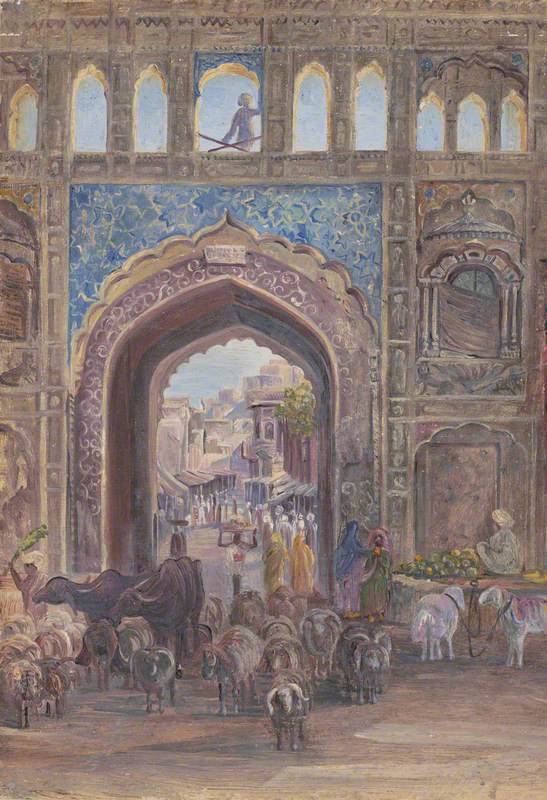

From the smallest of paint traces, researchers have been able to detect a wide range of colours, colour mixtures and even the use of shading. There aren't many examples of paintings or other materials that indicate how these sculptures would have looked in situ, but scholars have gleaned some information from the wall paintings in sites like Pompeii. 'We do see some renderings of very colourful architecture and a little bit of sculpture,' says Cecilie. 'We have to rely more on science and examinations of the sculptures themselves to be able to say something about their original polychromy.'

A visible-induced infrared luminescence (VIL) image showing the foot of an Amazon

The original and the painted copy of Caligula

There are careful, non-invasive ways to gather information from sculptures when their paints have been cleaned or decayed over time. The process begins with examination under a microscope, then may move onto methods like the photographic technique of visible-induced infrared luminescence (VIL), developed at the British Museum, to detect the pigment known as Egyptian blue. Researchers carry out a lengthy visual analysis and then consider how they may want to reconstruct a piece, including digital recreations and 3D reproductions in marble or plaster. 'When it comes to the original sculptures, we would never repaint them because our prime job at the museum, in my opinion, is to preserve these sculptures,' says Cecilie.

Thalia

2nd C BC, marble with traces of polychromy by Greek School

Gaining anthropological insight

In addition to getting a better understanding of how these objects originally appeared, we can extract other useful anthropological information from colour data. A couple of years ago, Cecilie and her team determined the original colouring of a sculpture of a man wearing a toga. They determined that the toga was orange, which indicates that the man was not an elite figure as originally thought – if he had been, he would likely have been depicted in a purple toga. With further research, they determined that the man was actually a freed slave. Studies like this provide a great opportunity to reframe the way we look at things and offer socio-cultural context in other areas, including fashion and class.

'What we see in museum collections are, in a way, skeletons – very beautiful skeletons,' says Cecilie. 'We can gain so much more knowledge on the interpretations of these artworks by adding colours.'

Has this changed the way you look at Greek and Roman sculptures? Did you already know about polychromy? Tweet us using #ArtMattersPodcast and let us know your thoughts. Also, be sure to listen to the full episode above to get fuller details on how researchers uncover the lost colour of classical sculpture.

Explore more

Art Matters podcast: artists' love for the colouriest colours

Listen to our other Art Matters podcast episodes