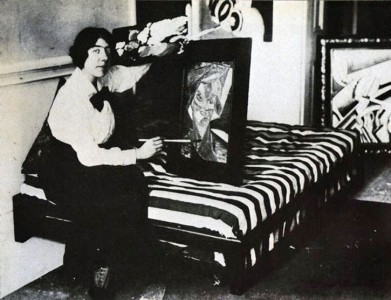

Barbara Hepworth is one of the most significant sculptors of the twentieth century, with a career that spanned decades of tumultuous political and social change. She is best known as a carver and this is how she would often describe herself, although her artistic output also incorporated painting, drawing, fabric design, printmaking, and making work in metal through various techniques.

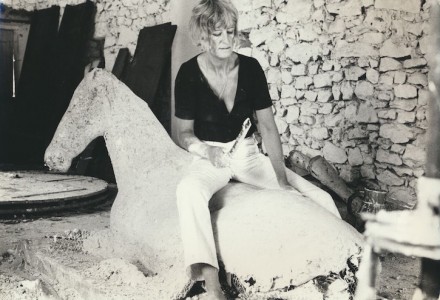

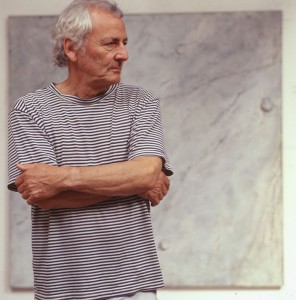

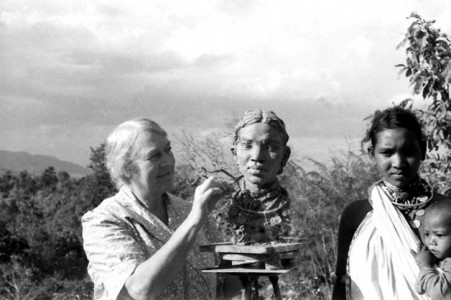

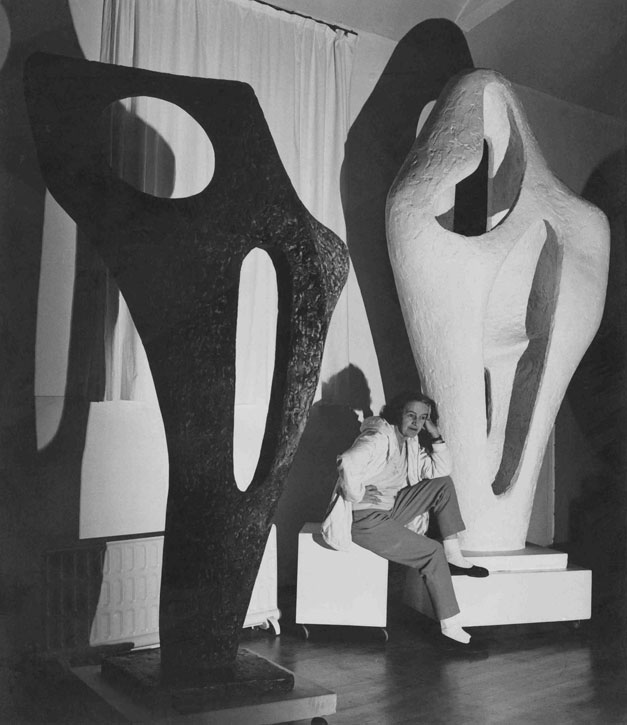

Barbara Hepworth with the plaster of 'Figure for Landscape' and bronze cast of 'Figure (Archaean)'

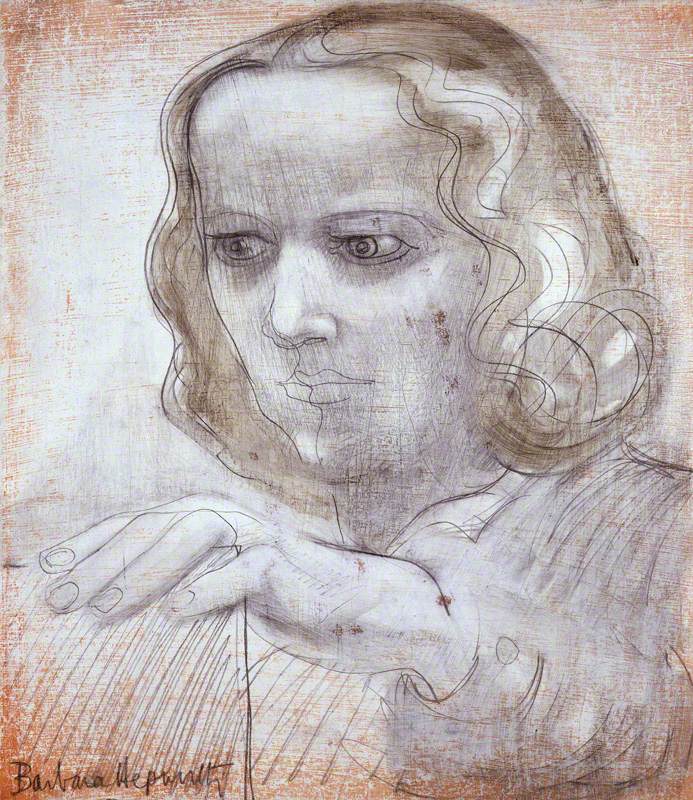

She was also a beautiful writer, producing eloquent statements on her art and philosophy throughout her life. Several of these texts reflect upon her personal life – her children in particular – and her broader cultural interests, from architecture, music and poetry to political activism, science and technological developments.

'Barbara Hepworth: Art & Life', currently on display at The Hepworth Wakefield, attempts to show the range of Hepworth's work, and how these interdisciplinary interests and lived experience infused her expansive practice.

Installation image of 'Barbara Hepworth: Art & Life'

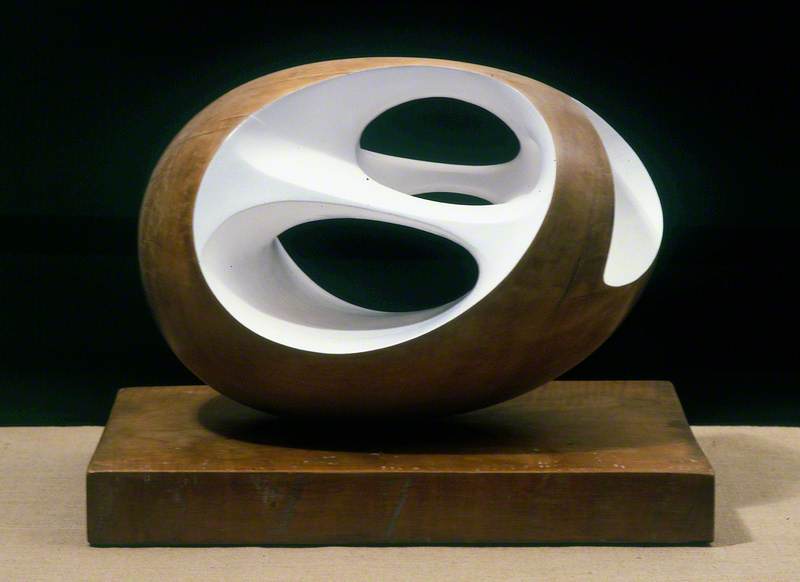

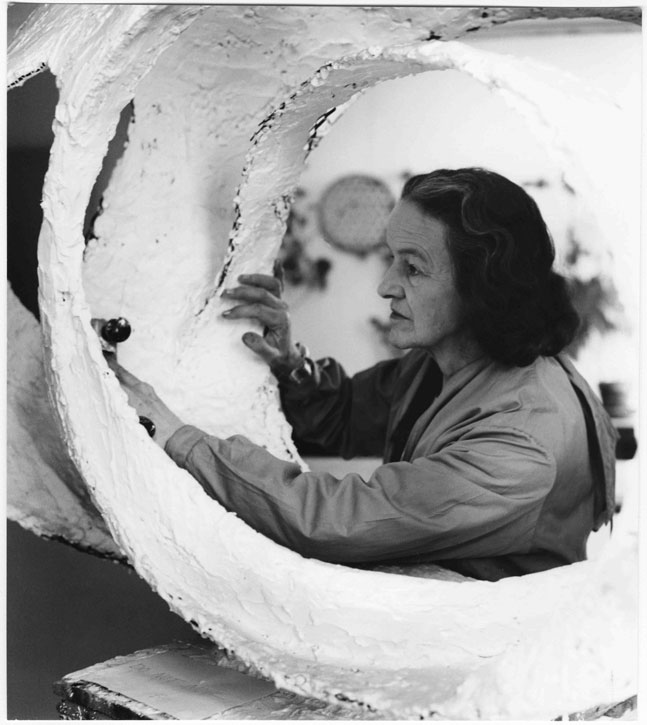

As one of the key figures of modern art, Hepworth's formal language is well established, and in 1941 she described in a letter to critic E. H. Ramsden how her sculptures carved in wood and stone shifted from figurative to abstract forms over the 1920s and 1930s. 'The Torso or figure became the Single Form, The Mother & Child or 'group' became a Two Form'. Hepworth continued to explain that the Head evolved into a spherical form, or 'Pierced Hemisphere'.

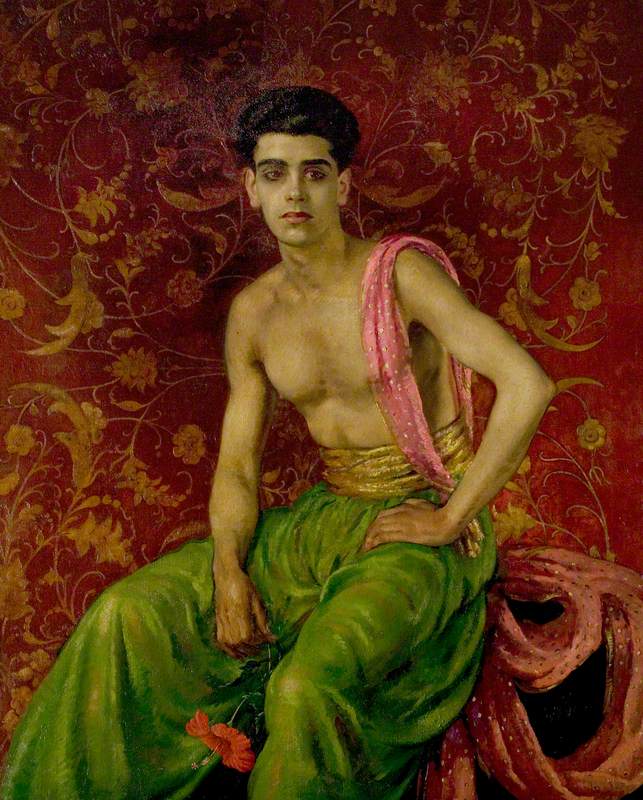

Hepworth later identified these three forms as those she was continually drawn to throughout her life, connecting the abstract shapes with particular ideas. The standing form, she wrote, 'is the translation of my feeling towards the human being standing in landscape', the two forms 'the tender relationship of one living thing beside another', and the oval or closed form expressing the 'feeling of the embrace of living things'.

Such tangible, physical realities – a figure standing at the top of a hill, a mother holding a child – are also ephemeral, emotional experiences, and much of Hepworth's work synthesises and somehow unifies seemingly contrasting concepts: matter and idea, the personal and the universal, the ancient and contemporary.

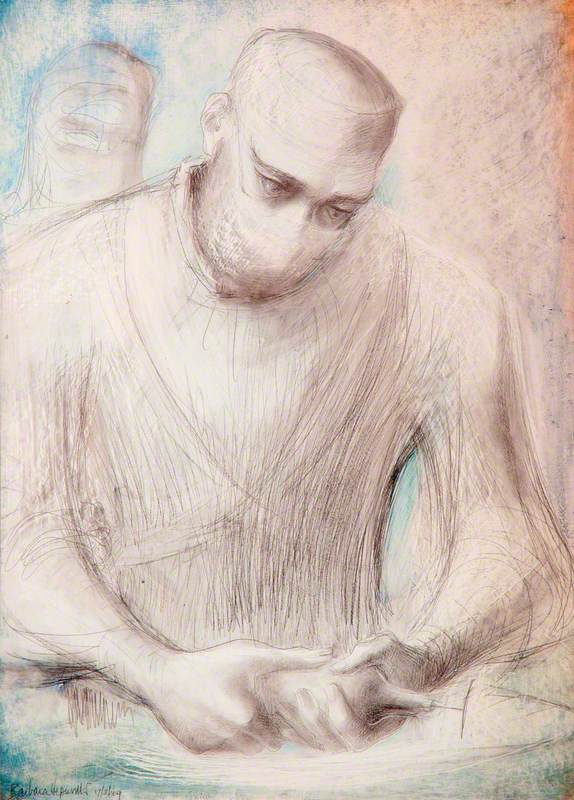

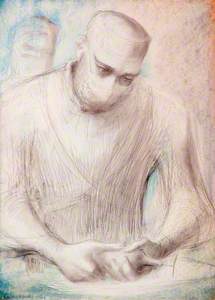

Hepworth returned to figurative work in the late 1940s, particularly in a series of paintings known collectively as the 'Hospital Drawings' that documented surgeons at work. She saw these different approaches – figurative and abstract – as being essentially connected, writing to critic Herbert Read, 'working realistically replenishes one's love for life, humanity and the earth. Working abstractly seems to release one's personality and sharpen the perceptions…The two ways of working flow into each without effort. It all feels the same – the same happiness and pain, the same joy in a line, a form, a colour...'

Two sculptures that were made for the Festival of Britain in 1951, brought together at The Hepworth Wakefield for the first time since, exemplify these diverse approaches. Contrapuntal Forms (1950–1951) comprises two monumental figures carved in blue limestone while Turning Forms (1950–1951) is an experimental, swirling abstract structure that rotated, made of cement constructed around a metal armature with a luminous white surface.

This foreshadows a process of working in metal that Hepworth developed in 1956. She began constructing metal armatures covered in plaster to cast in bronze, addressing the problem, as she posed: 'how to swing up and outwards when feeling cannot be contained by the [wood or stone] block?'

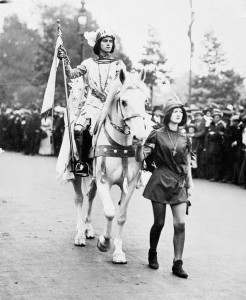

Just as Contrapuntal Forms refers to a musical term, several of these metal works refer to music in their titles, accompanying their freer, fluid forms. Curved Forms (Pavan) (1956) and Forms in Movement (Galliard) (1956) take their parenthesised titles from two Elizabethan court dances often paired together, the stately Pavan and lively Galliard.

Prototype for 'Curved Forms (Pavan)'

1956

Barbara Hepworth

Hepworth had won prizes for piano playing at school, and integrated her love of music into her working routine, as she wrote in 1952, 'my home and my children; listening to music, and thinking about its relation to the life of forms; the need for dancing as a recreation, and where dancing links with the actual physical rhythm of carving; the intense pleasure derived from tools and craftsmanship – all these things are daily expressions of the whole.'

Curved Forms (Pavan) is made of metallised plaster, plaster built up on an aluminium armature that was then sprayed with a coating of molton zinc, while Forms in Movement (Galliard) was made by bending copper sheets, a technique Hepworth also used in a series of sculptures titled Orpheus (1956).

In a notebook of 1961, Hepworth identified the disparate qualities she associated with 'metal and its properties': 'fire, running metal, molten – passionate, arrested movement – inducement of sound and resonance', distinguishing these from 'sheet under tension' which she linked to 'related rhythms of curves'.

Prototype for 'Winged Figure'

1961–1962

Barbara Hepworth

Hepworth's move to working in metal coincided with increasing opportunities to create public sculpture in the post-war period, for which bronze offered durability. A significant commission was Winged Figure (1963) for the John Lewis headquarters in Oxford Street, the full-size maquette of which is on permanent display at The Hepworth Wakefield. Hepworth wrote of this work, 'I think one of our universal dreams is to move in air and water without the resistance of our human legs. I wanted to evoke this sensation of freedom.'

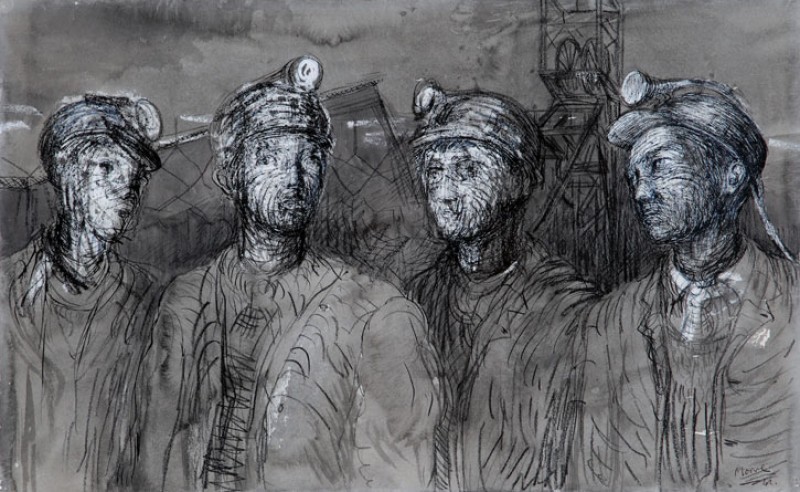

Presenting sculpture in public extended Hepworth's passionate belief in the artist's central role in society. Hepworth had always been politically engaged, participating in anti-fascist exhibitions in the 1930s, and writing in 1942 to writer and activist Margaret Gardener, 'we are v. much preoccupied (all of us) in thoroughly working out the living status of artist to Society and that will never be solved by a commission of fine arts but only by the artist being allowed to take his place along with other workers.'

In the post-war period, she became a campaigner for nuclear disarmament, writing 'to remain inert in this matter, or to argue over expediency, is to disbelieve in the power of good, and the moral courage generated by affirmative action.'

In 1956, Dag Hammarskjöld, Secretary-General of the United Nations, selected one of Hepworth's sculptures for his office, starting a correspondence that became a friendship due in part to their shared commitment to this cause. In September 1960 Hammarskjöld was killed in a plane crash, and Hepworth created several sculptures in his memory, culminating in the monumental Single Form (1964), permanently situated outside the UN headquarters in New York. Its shield-like form is comprised of many parts, and recalls neolithic standing stones, providing as Hepworth described, a 'symbol of both continuity and solidarity for the future.'

In a speech at its unveiling, Hepworth described Hammarskjöld as having, 'a pure and exact perception of aesthetic principles, as exact as it was over ethical and moral principles. I believe they were, to him, one and the same thing.' She could have been speaking of herself.

Hepworth lived in a time of astonishing technological advances and believed that these should inform the creative arts, noting at the end of the decade that the 'discovery of flight has radically altered the shape of our sculpture, just as it has altered our thinking'.

However, she embraced the impact of scientific advances with a sense of spirituality, writing in 1966: 'I regard the present era of flight and projection into space as a tremendous expansion of our sensibilities, and space sculpture and kinetic forms are an expression of it; but in order to appreciate this fully I think that we must affirm some ancient stability.'

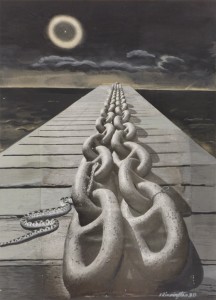

In later life, this dichotomy infused her practice, many works including 'moon' in their title – particularly around the time of the lunar landings in 1969 – while celestial bodies also appeared in works with religious references, like Genesis III (1966) or Construction (Crucifixion) (1966).

Construction (Crucifixion)

1966

Barbara Hepworth

To the end, Hepworth's work combined seemingly contrasting ideas. In 1965, the same year she lent her support to an appeal for peace in Vietnam, Hepworth wrote in the Christian Science Monitor that sculpture should be an 'act of praise, and enduring expression of the divine spirit'.

Barbara Hepworth at work on the plaster for 'Oval Form (Trezion)', 1963

Her gentle but determined approach in creating a conversation between opposites reflects an understanding and appreciation of the complex world we live in, and a belief in the power of people to shape it.

Eleanor Clayton, curator at The Hepworth Wakefield

'Barbara Hepworth: Art & Life' at The Hepworth Wakefield runs until 27th February 2022.