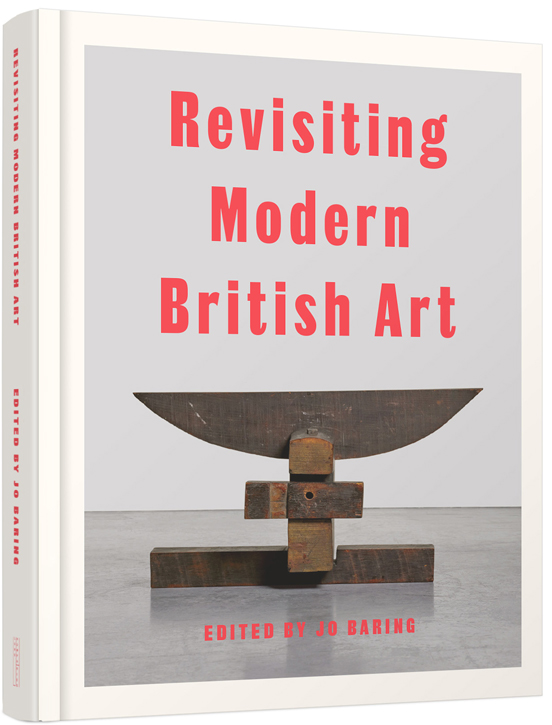

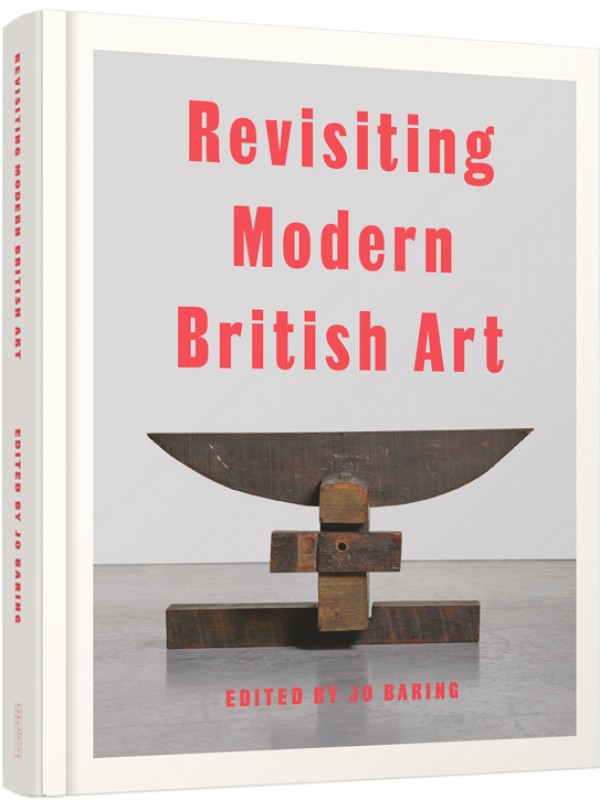

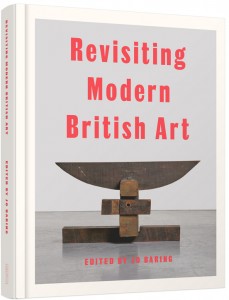

Reading back my article on expanding British art for the book Revisiting Modern British Art, originally conceived and written last year, is an excellent exercise and proof of concept regarding the acceleration and high-speed expansion of history. So much has happened since and so much more is yet to unfold.

The essay itself, as is true with much of my work – by way of curating, public speaking and writing – was a very personal call to arms, particularly arresting and emotionally charged as it came at a tipping point of cultural history as discussions of race, class, the systematic erasure of histories and the deep-rooted hierarchical backbone of history bubbled to the surface.

Since then we have faced many tipping points – I write this revisiting of my initial revisiting of modern British art at a time when my attachment to Britishness is further being negotiated: the recent passing of Her Majesty the Queen has jostled nationalistic admiration but also allowed us to reflect on how fixed the nation's ties are to symbols of empire. It has shown how, despite fast-forwarding discussions regarding racial inequality and socio-economic injustices, Britishness nostalgia, in a Union Jack-Victoria Sponge-Paddington Bear sort of way, is comforting and luxurious.

At its roots, the essay in the book examines a few simple questions: Where are you from and how does that impact you? How do you represent where you are from? And why is that question more nuanced than it might initially seem?

I describe nationalist sentimentalities because I feel as though the categorisation of a nation is inherently complicated, has always been and is increasingly so – but also they strike at the deep, historic inequalities that narrow stereotypes have brought out. In making something the exemplar of Britishness and having such tightly woven shackles of our own making, British art history has overlooked many important art movements that have forged important histories of creativity, resilience and community.

The frequently told story, from many communities of colour that have made other places their home, details questioning of 'where are you really from?' Whilst we agree and understand this problematic line of enquiry, that at its core destabilises the construction of one's identity, this is easily transplanted when looking at art. We still have a problem with perception. And this comes because Britain has an enduring reluctance to look at and confront the past.

When did expanding national identity become taboo? Britain is a nation of unanswered questions, avoided subjects, and contradictions – and seeing that explored in art, finally on home turf and elsewhere is exciting.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York recently unveiled the third instalment of its annual façade commission by Guyanese-British artist Hew Locke. The work, Gilt – an apt pun on the word 'guilt' – is a suite of sculptures that, in impressive theatrical fashion, reference the complex history of the museum collection – interrogating the history of the objects from various cultures, how they came to be there, and what it means now they are there.

Speaking to the relationship between guilt and gold across 3,000 years of art history, "Gilt" explores global histories of conquest, migration, and exchange.

— The Metropolitan Museum of Art (@metmuseum) September 15, 2022

Photos courtesy of Hew Locke; Hales Gallery, London; and PPOW, New York. pic.twitter.com/OyBc8xYjIL

At the core, the work serves as an emblem for the colonial entanglements of the museum, and the imprint of colonialism which will stay with the many objects globally even after restitution – but it is also a deconstruction of the Eurocentric narrative, and its associated iconographies, that come to symbolise British history and Britishness. Perhaps colonialism is as British as corgis?

Inherently, it is difficult to categorise British art. British art, often considered English art internationally, has been criticised for its provincialism. Can there really be a common theme to art made in one place – in its most literal sense, British art is art made on these isles, but in this, how do we collect the art of Black British, Asian, and female perspectives, amongst the horses and aristocratic portraits in gilded frames and tie it up neatly in a Union Jack printed bow? What connects us?

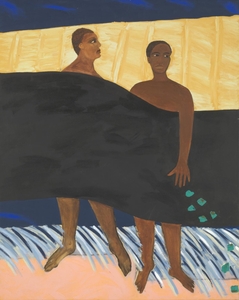

Black British History is British History

2020

Greg Bunbury

This problem extends beyond Britain also. 'American art', as a catch-all phrase, works best to describe certain moments (Whistler, early 1940s Abstract Expressionism, 1950s Neo-Dada, Pop Art, 1960s Realism, and the ongoing Post-Modernism experiment – recently including Harlem Renaissance). European art extends to typify almost all of art history.

African art suffers, not least because it scrambles to tie a thread between a continent, but also because the displacement of the cultural histories of many African nations lies at the hands of those who seek to categorise it in one grand swathe. It is a colonial act – and an ongoing one – to displace cultural history and conveniently rename it.

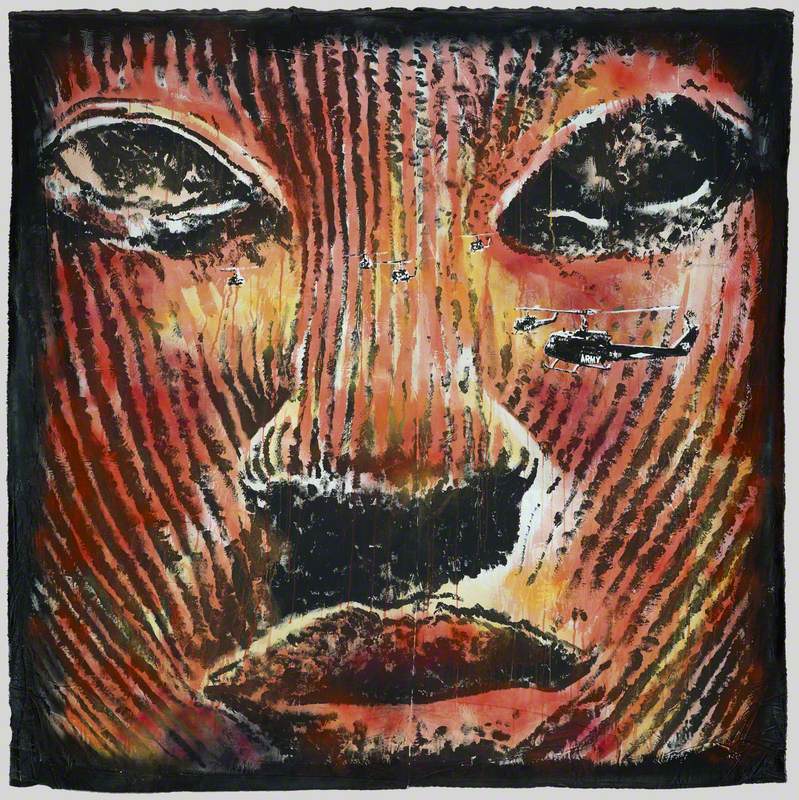

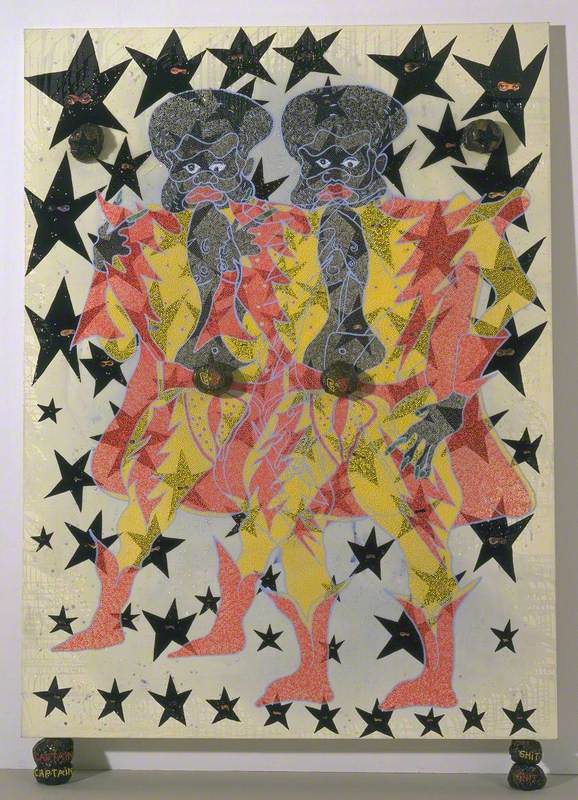

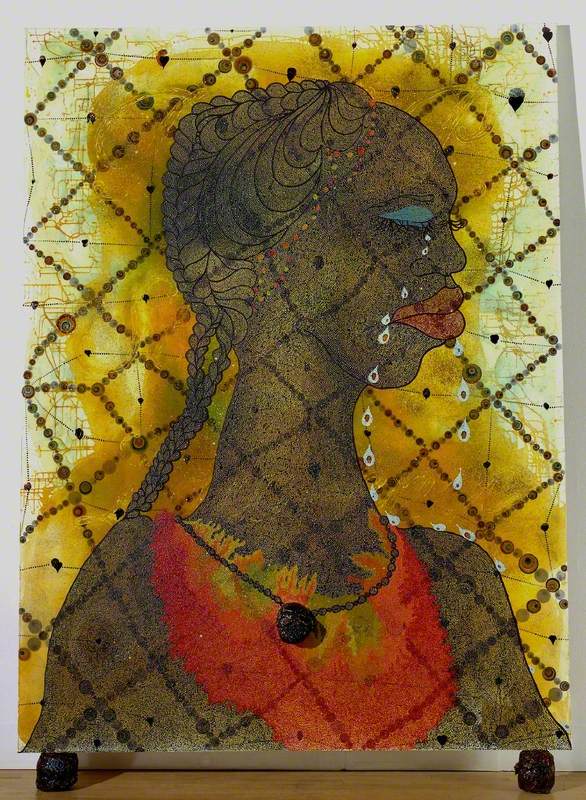

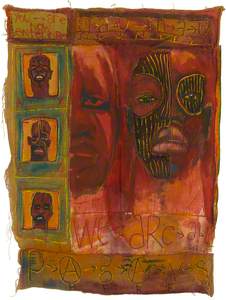

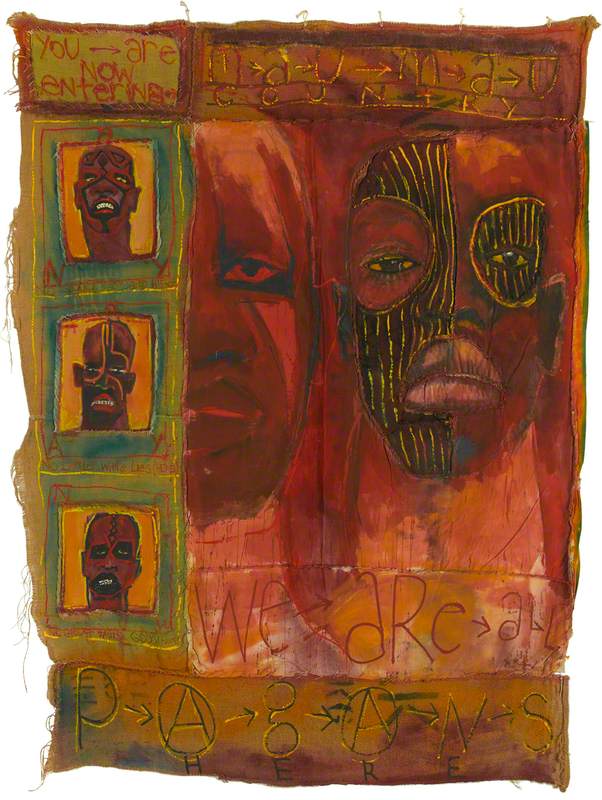

(You are now entering) Mau Mau Country

1983

Keith Piper (b.1960)

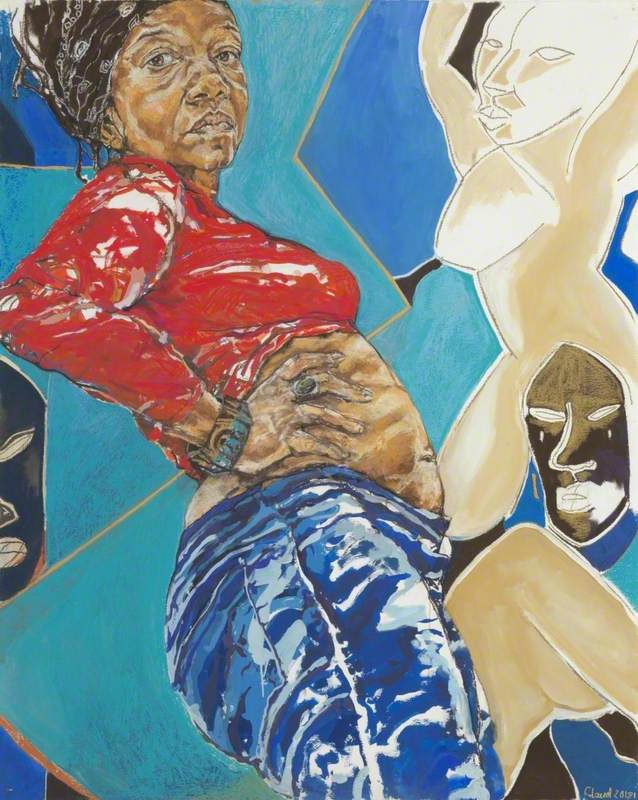

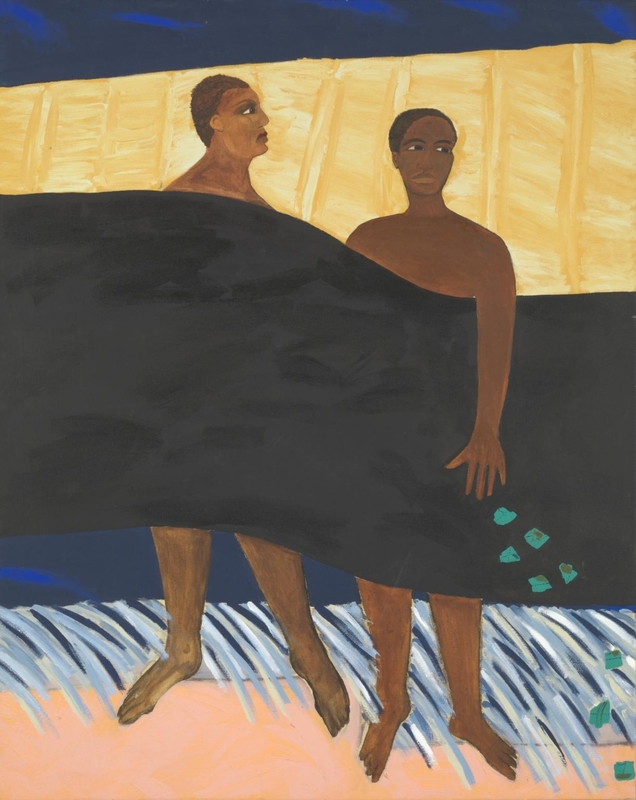

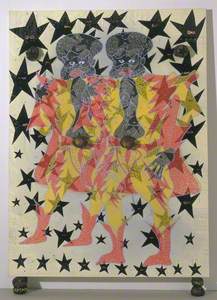

People often merit the Young British Artists (YBA) movement with revitalising a generally boring British cultural life. And there is truth to that because the art world had been entirely overlooking the BLK Movement which had been refashioning the way we see art – a few years before the 'Sensation' show and notably four decades before the artists involved would receive their long overdue recognition.

The BLK Art Group were a radical cohort of young artists whose work tackled shootings, racism and the uprising of the 1980s. It was a potent time – Margaret Thatcher became prime minister in May 1979, and Eddie Chambers made an artwork called Destruction of the National Front.

Then 19 years old, Chambers was studying in Wolverhampton – a central base for the BLK Group. The reconfigured Union Jack as a swastika, then further shattered and disjointed into fragments across four panels, stood as a rebuke of an encroaching far-right sensibility. It has come to represent the anger of Black Britons of the time, and an ongoing reminder of the far-right's particular deftness of reappearance.

In 1979, Chambers would found the BLK group, stylised as BLK, but pronounced 'Black', with the motivation of combating racism with work that approached the Black experience in Thatcher's Britain.

This group included Eddie Chambers, Dominic Dawes, Claudette Johnson, Wenda Leslie, Ian Palmer, Keith Piper, Donald Rodney and Marlene Smith and would influence artists such as Lubaina Himid, Sonia Boyce, Yinka Shonibare, Chris Ofili and Steve McQueen.

When I think of the landscape of British art today, this contemporary present could not have happened without these artists, laying the land and wrestling with a political landscape that has come to represent a pivotal time in British history.

Aindrea Emelife, curator and writer

Revisiting Modern British Art, edited by Jo Baring, is published by Lund Humphries on 10th October 2022