Repeat the space where the swallows try their turns

Reveal the place where the ants begin to crawl,

Remove the time when the rain begins to drip,

Re-seal it all.

– Emmy Bridgwater 'Closing Time', quoted in British Surrealism, exhibition catalogue edited by David Boyd Hancock, Dulwich Picture Gallery, 2020

'Surrealism for me draws its inspiration from Nature... You see the shape of a tree, the way a pebble falls or is framed, and you are astounded to discover that dumb nature makes an effort to speak to you, to give you a sign, to warn you, to symbolise your innermost thoughts.'

– Eileen Agar, A Look at My Life, Methuen, 1988

I was invited to contribute a chapter to Revisiting Modern British Art, edited by Jo Baring, just days before I was due to begin a period of jury service at The Old Bailey, London. Jo asked me to write about British surrealism and the natural world, a task that I was delighted to take on having just curated the exhibition 'Eileen Agar: Angel of Anarchy' at Whitechapel Gallery and with, what I thought would be, two weeks in court ahead.

I decided to write about the dual influences of nature and landscape, and magic and mysticism on the development and evolution of British surrealism. Focusing on the way that the British landscape is embedded with myriad histories – geological, mythological and magical – I sought to examine the various ways that the British surrealist artists harnessed these narratives – from depictions of sacred landscapes and ancient stone structures to the use of found organic objects as talismans or totems within assemblages, collages and photography. My aim was not to make the claim that all surrealist art created in Britain is – or was – about the magic of nature, but rather to chart this seam as a strong and foundational theme within the movement.

Surrealism, as history delineates, originated with French poet Guillaume Apollinaire in 1917 and blossomed as a literary, philosophical and artistic movement across the 1920s and 1930s. Defined though a championing of the irrational and the unconscious, a revelry in dreams, use of surprising juxtapositions, and revolutionary activity, the movement's aspirations towards liberating the mind also related to political freedom as surrealism's protagonists across the world were deeply anti-war and held political affinities with the radical left.

As surrealism's origins were literary it makes sense that its first moments in the UK came through publications and journals, before then flourishing into the presentation of exhibitions of the work of both European and burgeoning British surrealist artists.

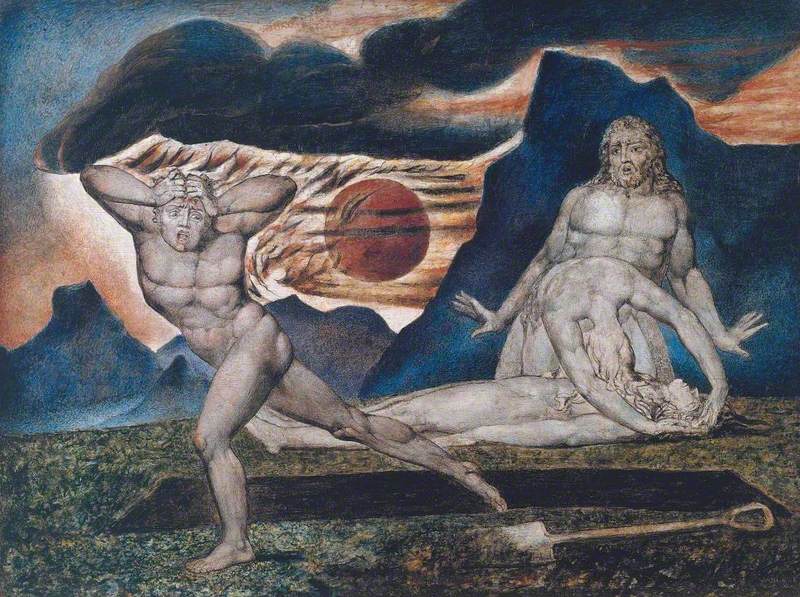

Several of these British artists – including Paul Nash and Eileen Agar – cited British Romantics such as William Blake, Jonathan Swift, Samuel Palmer and Lewis Carroll, who had roots in traditions of landscape and mythology, as precursors to the development of their surrealism. Agar even described Carroll in her autobiography A Look at My Life as 'a prophet of surrealism.'

These ideas filled my thoughts as I began my first day in court, expecting a two-week jury service or perhaps even to be sent home. What I embarked upon however was a three-month trial that was complicated, revelatory, deeply sad and highly traumatic. Days in court are long and laboured but contrary to popular belief, while not in court, jurors are permitted to use computers and phones when waiting the long stretches for 'legal work' to be completed.

And so, the following three months became a surreal mix of serious crime and welcome hours of research escaping into the imagined and fantastical landscapes of the British surrealists.

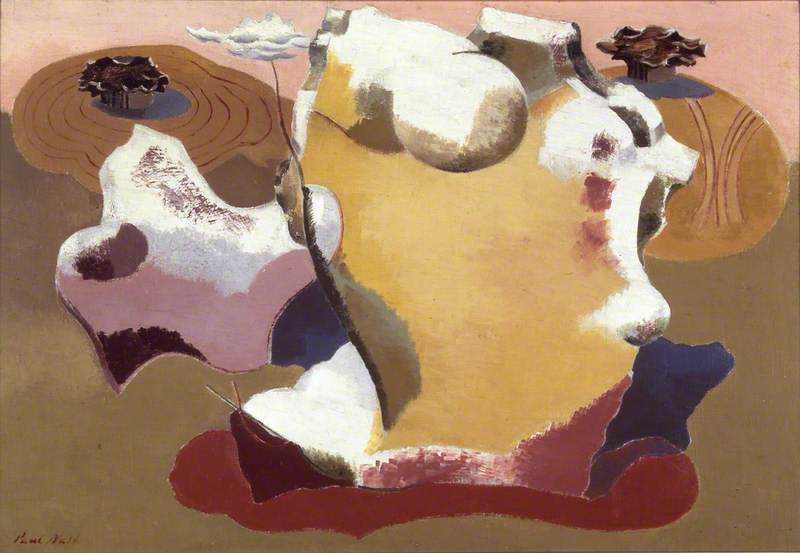

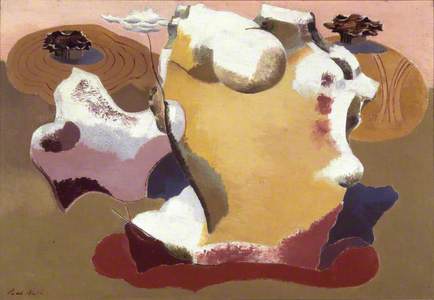

Paul Nash (1889–1946) is probably the most well-known of the British surrealists and he certainly saw himself in the tradition of Blake and Palmer. For Nash, the British countryside was an endless source of inspiration and he persistently sought ways to reimagine it toward the ideal of building a new world. Landscape of the Megaliths (1934) reveals Nash's enduring interest in places of collective remembrance and ancient history.

It presents a pre-industrial, uninhabited aerial view of Avebury Stone Circle – pink, sunset-tinged and devoid of any unnecessary adornment. The work is not a description of a physical landscape but rather it presents its atmosphere – what Nash called the genius loci – by allowing its histories, mythologies and natural features to coalesce in one image.

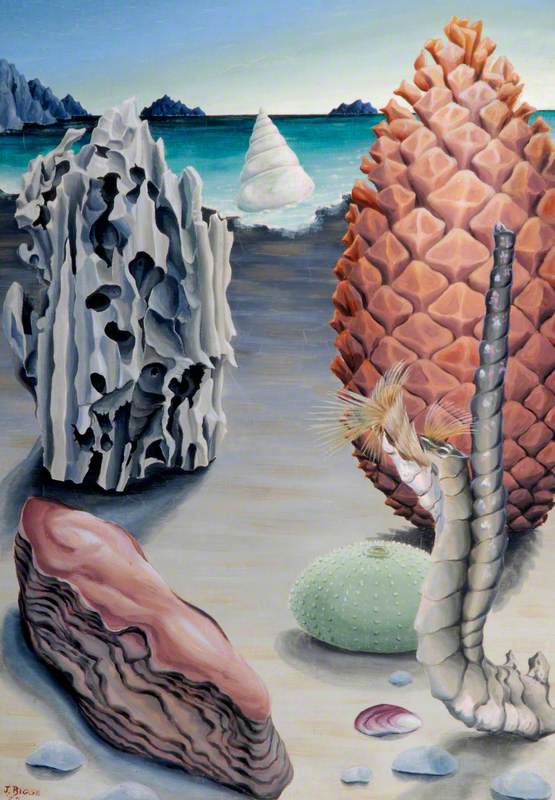

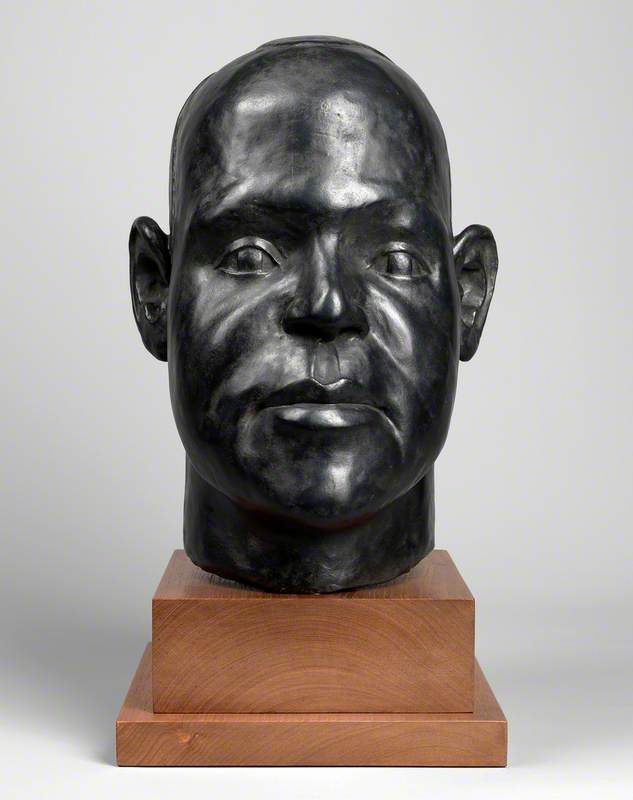

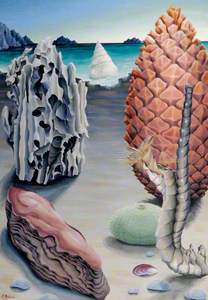

John Selby-Bigge (1892–1973) was a member of Unit One – a British grouping of modernist artists founded by Nash in 1933. Deeply interested in surrealism, his Composition (1939) deliberately morphs and enlarges three seaside items; a pinecone, a lump of bleached coral and a blush oyster shell, to resemble menhirs or a group of creatures in conversation.

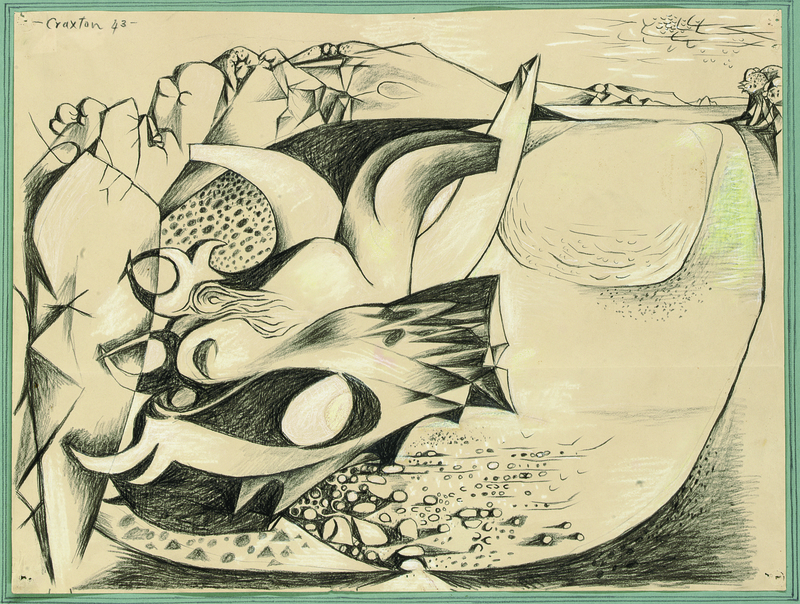

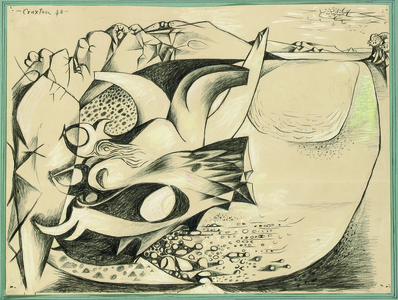

In contrast to this somewhat pastoral evocation, Graham Sutherland (1903–1980) and John Craxton (1922–2009) drew on the visionary romanticism of Palmer but twisted the influence in a more Pagan direction. Their ominous landscapes render the fields and coastlines of Britain strange, using colour and movement to distort the natural world in a way that filled it with the angst of the time. Created during the disasters of the Second World War, these works contain an atmosphere of confusion, mutation and uncertainty – on both a natural and societal level.

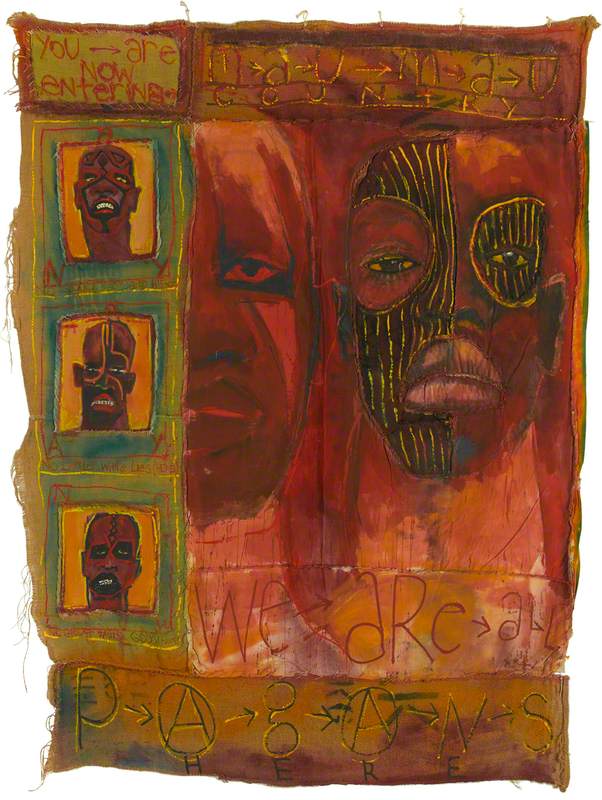

Similarly political, the women of surrealism engaged in a simultaneous pursuit to establish their identities as artists rather than muses, whilst also following their distinct creative aspirations. Frequently depicting themselves as pre-Christian female archetypes: goddess, alchemist, visionary, witch or Mother Earth, they took inspiration from well-known mythologies and Pagan themes.

Artists such as Emmy Bridgwater (1906–1999), Stella Snead (1910–2006) and Marion Adnams (1898–1995) created dreamlike paintings of mythical and magical universes in which women possessed supernatural powers that operated within and through the animal and natural worlds. Adnams' diminishing eyesight forced her to give up painting in 1968.

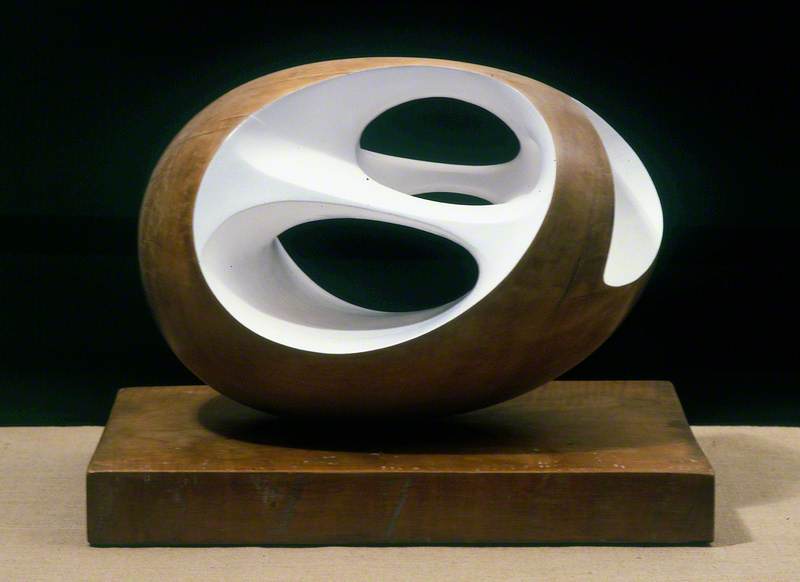

Her last work, Three Stones (1968), presents three irregularly shaped stones, icy-cream coloured with a bone-like texture; the centre of each stone is bored out with a circular hole resembling a mournful, singular eye. The work was shown in the 2018 exhibition 'Marion Adnams: A Singular Woman' at Derby Museum. Of making the work Adnams said: 'I had worked with one eye (and a poor one at that) putting down what I knew, rather than what I saw. Now I worked with a kind of passionate fury, defying the fates, feeling rather than seeing.'

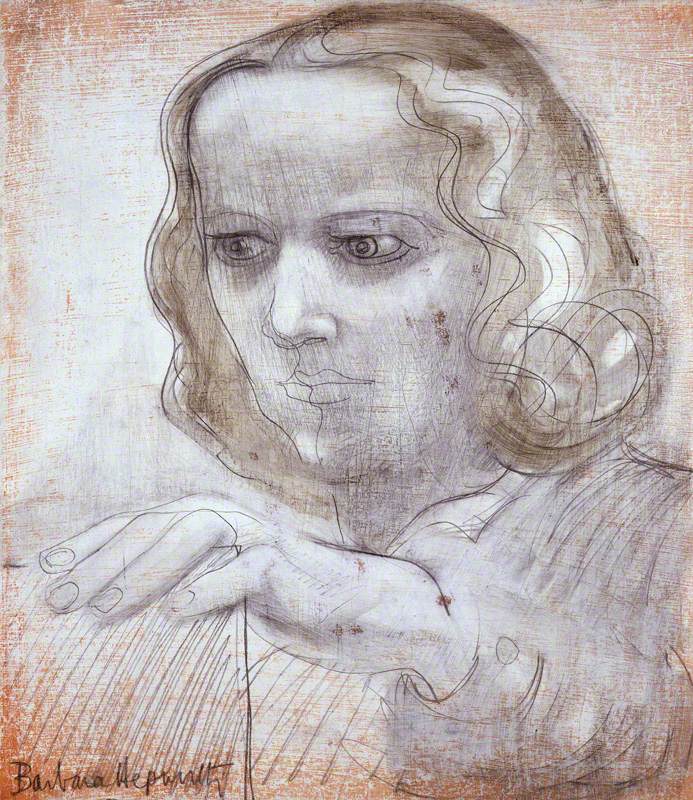

Perhaps the most familiar of the women surrealists in Britain, Eileen Agar (1899–1991) was deeply fascinated by nature and sought the surreal in the organic world rather than the manmade or the unconscious.

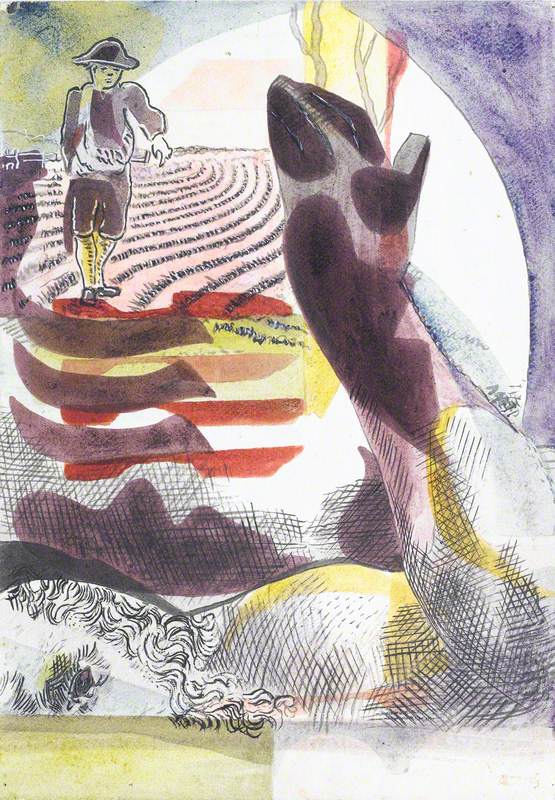

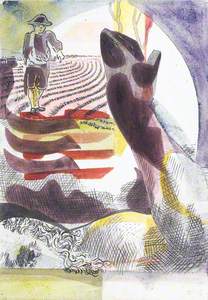

The Sower (1937) is one of several of Agar's works of the late 1930s that explore themes of life, death, the passing of time and the cycle of the seasons. In this dream-like image, a sower in a furrowed field appears as a metaphor for the beginning of life, sowing the seeds, which will bring forth crops. Along the bottom of the image lies a figure, which may be a Pagan Green Man, spirit of the harvest, who often has the body of a faun – his cross-hatched hoof reaches up to the landscape above, heralding the arrival and new life of spring.

Of all the British surrealists, perhaps the artist most invested in magic, the occult, and its intersection with nature, was Ithell Colquhoun (1906–1988). Colquhoun's surrealist works use natural forms to tell stories around sexuality, natural forms and energy flows.

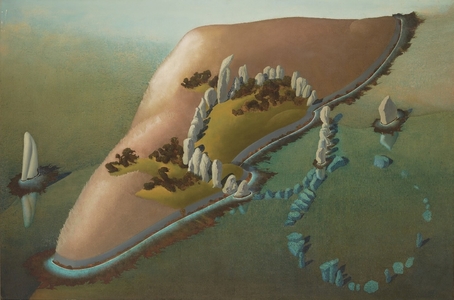

La Cathédrale Engloutie (c.1950) envisions two adjoining stone circles forming a figure of eight, atop a small island surrounded by ocean.

Inspired by the stone circles on the islet of Er-Lannic in France, Colquhoun's scene anthropomorphises the landscape in a way that makes the island feel almost human, a feeling that is enhanced through her use of pink to depict the land itself, so much so that it becomes a breast, breathing through the ocean. She highlights this mastery of nature over the manmade through the work's title which references Claude Debussy's musical description of a legendary Breton cathedral, sunk beneath the waves, that miraculously rises up from the sea on clear mornings when the water is transparent.

The British surrealists combined the influence of European modernism with an innate attitude to the natural world that found ready reception in the anxiety of the interwar period, and – personally for myself – the angst of an ongoing court case. Their output encapsulated both the romantic tradition and its recourse to native, often mythical and mystical landscapes with a modern visual vocabulary that was entirely new and fresh. By insisting on the vitality of the past and the effervescence of nature as an appeal for alternative ways of understanding the earth, these artists were suggesting alternative ways of living, alternative ways of collaborating with the world and, in many cases, even alternative worlds.

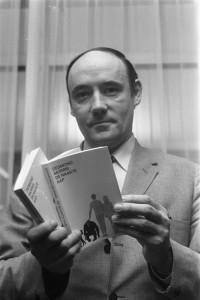

Laura Smith, Curator at Whitechapel Gallery

Revisiting Modern British Art, edited by Jo Baring, is published by Lund Humphries on 10th October 2022