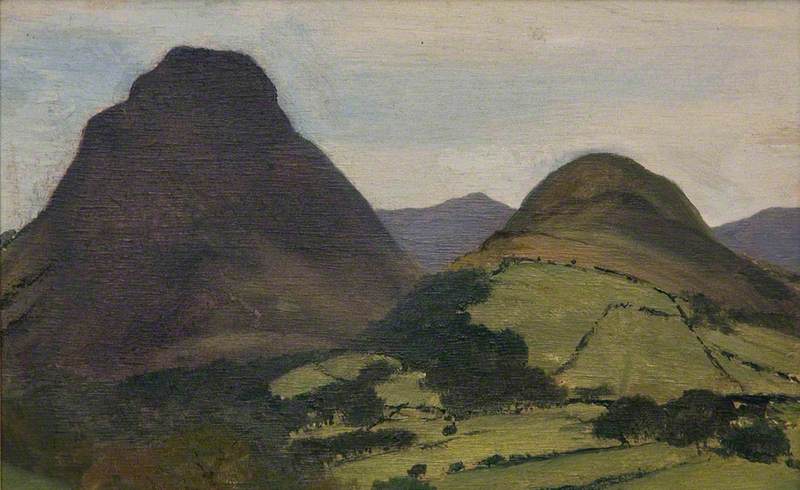

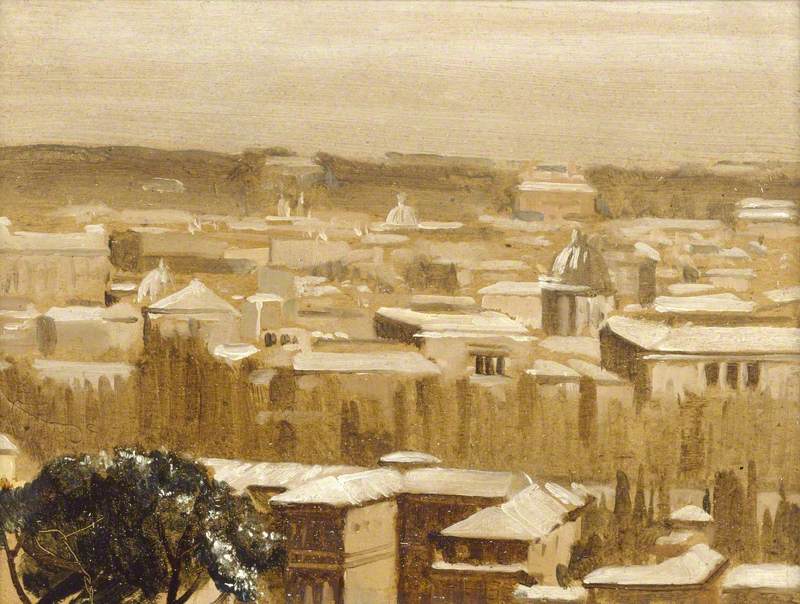

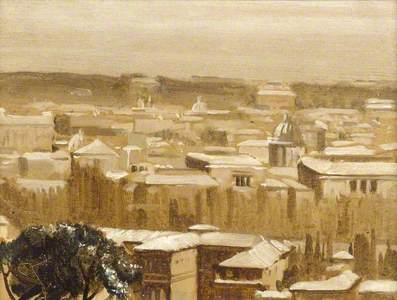

Derek Hill first visited Donegal at the invitation of connoisseur and collector Henry McIlhenny of Glenveagh Castle. The two men had met in Italy where Derek spent a great deal of time during the decade following the Second World War. These years were fruitful for him. In 1951, he was appointed to the board of governors of the British Institute in Florence, and he was assigned the role of art director at the British School in Rome between 1953 and 1955, and subsequently from 1957 to 1959.

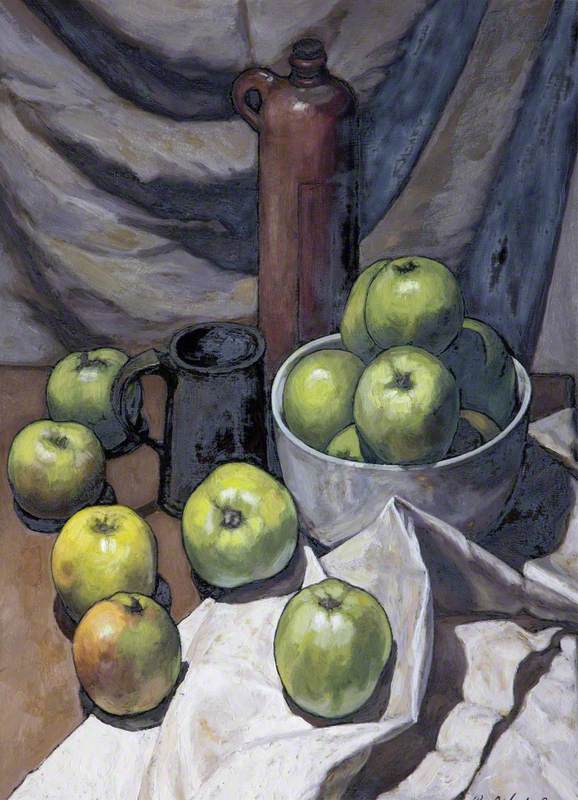

Arguably as significant for Derek as his academic achievements during this time was the fact that a burgeoning passion for landscape painting found fuller expression in Italy. This was not least due to the mentoring of the art historian Bernard Berenson, who lent him a small house on the grounds of his great villa, I Tatti, in the Tuscan hills near Florence.

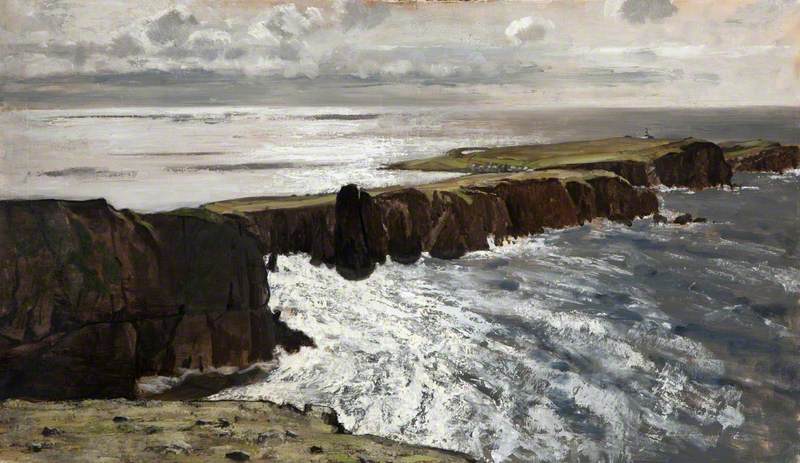

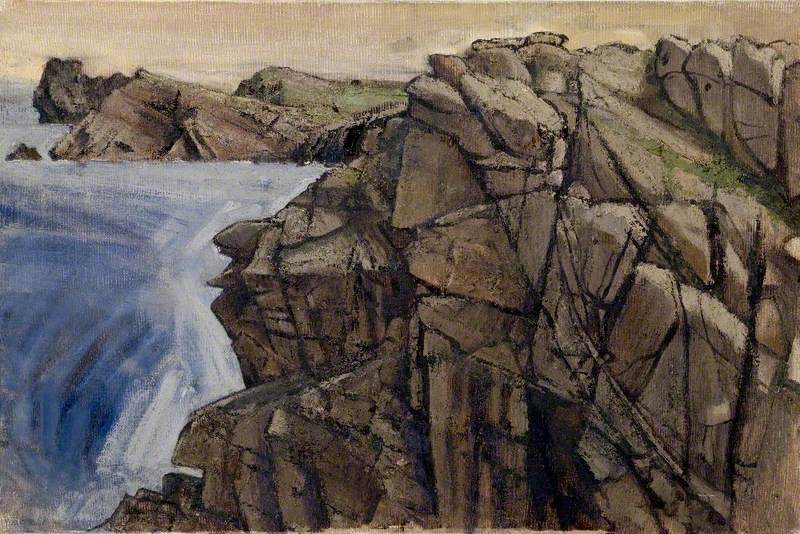

Having left Marlborough College at the age of 16, Derek's artistic career began when he went to Munich to study set design, encouraged by his brother John, who was a successful interior decorator. Here the influence of the Bauhaus seems to have instilled in him a strong sense of geometry, which is often apparent in the linear constructions within paintings such as Cliff Face, Tory Island of 1958. In conversation with Lord Gowrie, the artist said, 'In Munich I did endless geometric exercises and my best landscapes have a completely abstract geometrical drawing underneath them'.

Next to art, travel was Derek's greatest passion. By the time he was 21, he had already traversed the Soviet Union, going on to Japan and China via Siberia, and subsequently to Bali, where he lived for about six weeks in the mountains with a local family. During his youth, Derek developed a keen interest in Islamic culture and architecture which led to the publication of several scholarly books on the subject during the 1960s and 1970s.

Mount Athos, Waiting for the Early Boat

1980

Derek Hill (1916–2000)

John De Vere Loder, 2nd Baron Wakehurst (1895–1970), Governor of Northern Ireland

1959

Derek Hill (1916–2000)

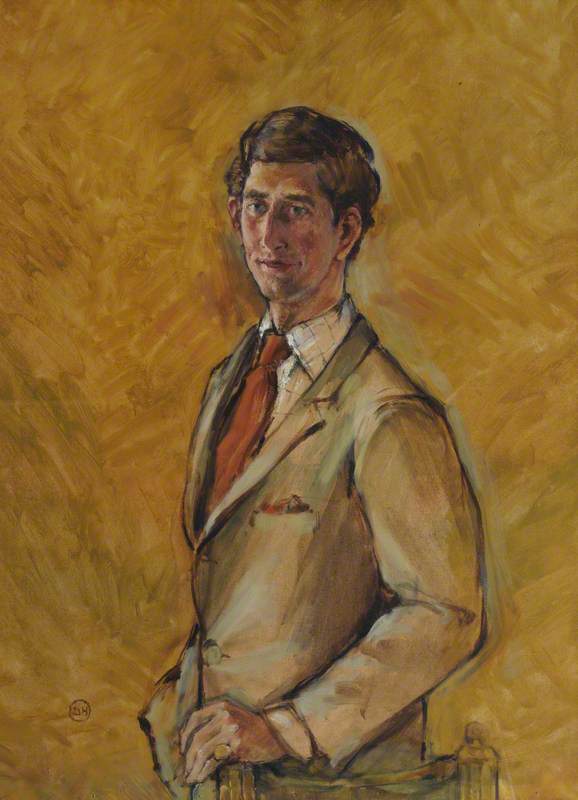

Charles III (b.1948), when Prince of Wales, Honorary Fellow

1971

Derek Hill (1916–2000)

Given these diverse cultural interests and his intrepid nature, it doesn't seem unusual that a painter of private means, primarily known for his society portraits, should be inclined to put down roots in the farthest reaches of the Irish western seaboard. In 1953, McIlhenny drew Derek's attention to the vacant St Columb's Rectory (now Glebe House) overlooking Loch Gartan near the small village of Churchill, County Donegal. Derek immediately fell in love with the place. It would become his main home for the remainder of his life, although he continued to travel widely.

Midnight at Tory Island (Toraigh), County Donegal, Ireland

1980

Derek Hill (1916–2000)

Tory Island (Toraigh), County Donegal, Ireland, Evening

(from Derek Hill's hut) 1980

Derek Hill (1916–2000)

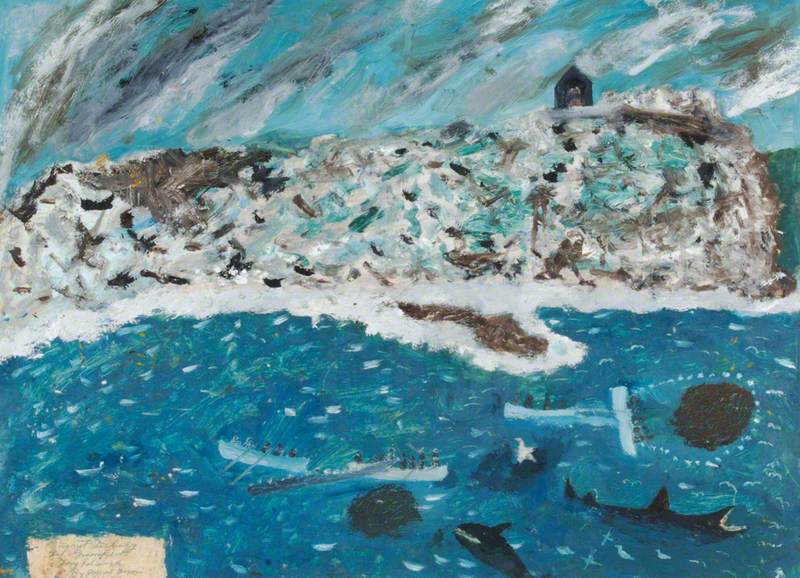

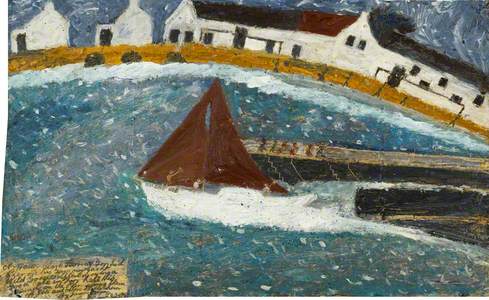

In 1958, Derek made his first visit to Tory Island, an unforgiving expanse of rock and cliff, less than a mile wide and about three miles long, off the northwest coast of County Donegal. Tory, or Toraigh in Irish, means 'Rock of the King', and to this day the islanders maintain the tradition of electing a king for their community of around 200 inhabitants. One can only imagine the intrigue with which this small secluded population must have viewed the arrival of an English artist, who set up his painting studio in a tiny hut, without running water or sanitation.

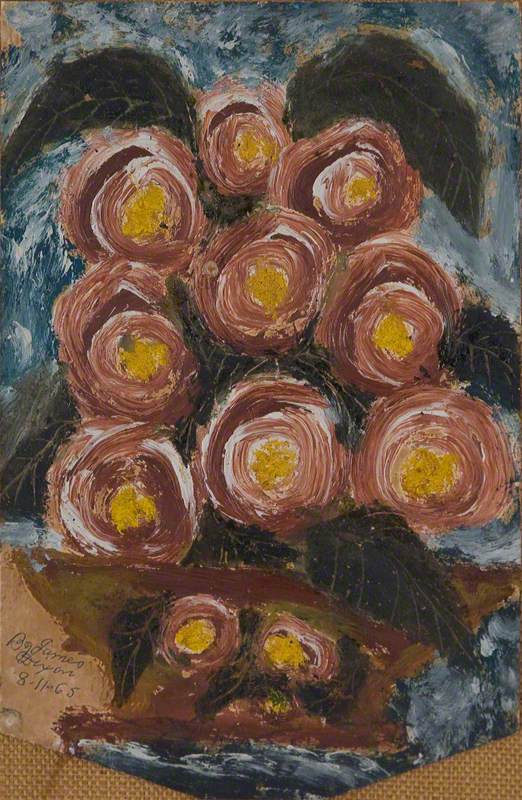

The popular story goes that a group of islanders came across Derek Hill painting en plein air one morning when coming from mass. One amongst them, James Dixon, enquired as to what the gentleman was doing and, when Hill replied that he was painting, Dixon inspected the canvas and responded that he could do better himself. Derek good-humouredly accepted this challenge and agreed to provide Dixon with paper and painting materials for his efforts. From this meeting, a unique and somewhat eccentric friendship evolved between two artists who would each become significant figures in the history of twentieth-century British and Irish art.

There has been an assumption that their meeting was the catalyst that initiated James Dixon's artistic life, which is not, in fact, true. During the preceding years, Dixon gifted a number of his paintings to the yachtsman Wallace Clark, proving that he had established his painting practice before the friendship with Derek began.

What is certain is that the men encouraged each other. Each benefitted from a mutual cultural exchange, and Dixon, not least from the supply of better quality materials, although he refused to give up the use of a donkey-hair paintbrush. Undoubtedly, it is at Tory that the landscape painting that progressed during Derek's Italian years reached maturity.

Two Sailing Ships with a Lighthouse

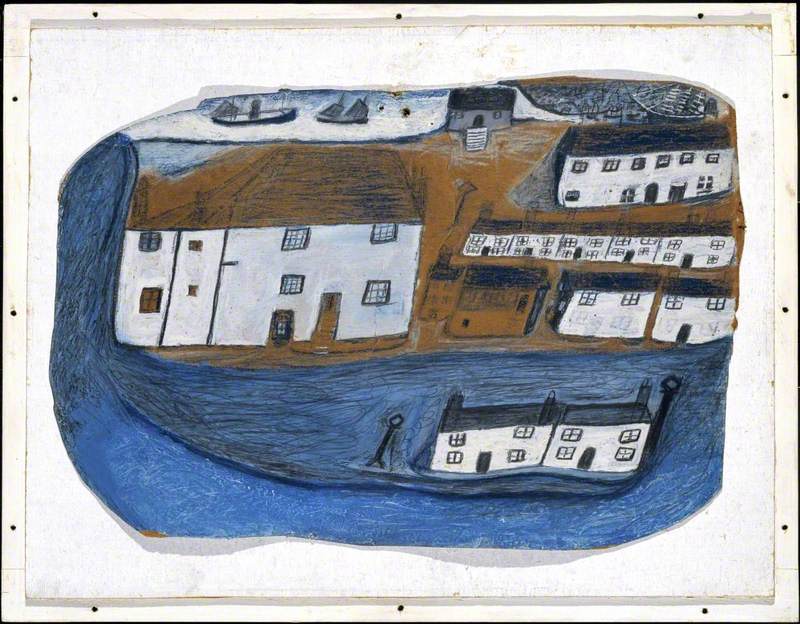

Alfred Wallis (1855–1942)

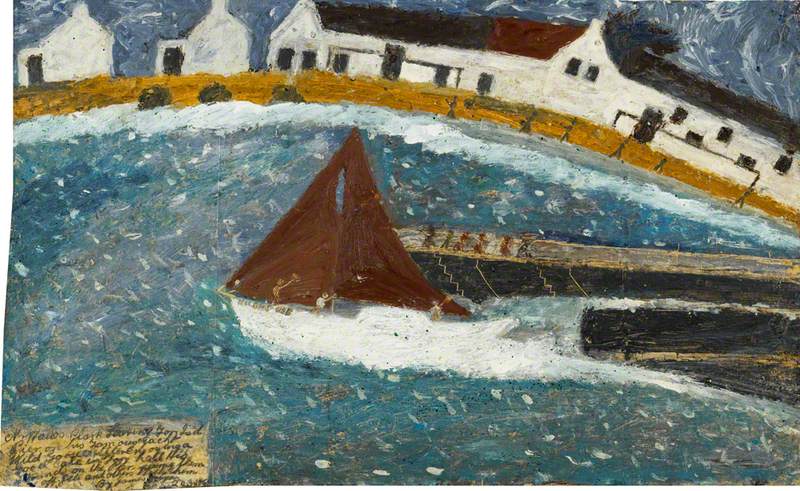

Dixon's naïve style may be compared to that of Alfred Wallis (1855–1942), the St Ives painter from a previous generation. It seems highly improbable that Dixon would have ever seen an example of Wallis's art, but nonetheless, they have much in common in stylistic terms. It may just be coincidence, but is interesting to consider that both men came to painting in later life, had no formal training (apart from social interaction with a small cohort of contemporary artists) and were part of a seafaring, coastal community, used to viewing the world from the ocean. This latter aspect, one might argue, is perhaps what has resulted in the sense of vastness in Dixon's painting. Invariably, his paintings successfully articulate the experience of living on a small island at the mercy of the natural world around it.

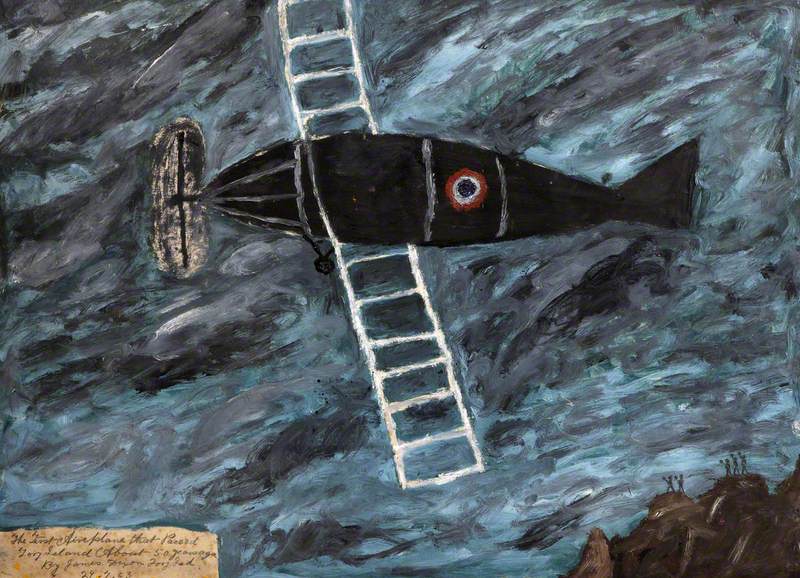

The First Airplane that Passed Tory Island

1963

James Dixon (1887–1970)

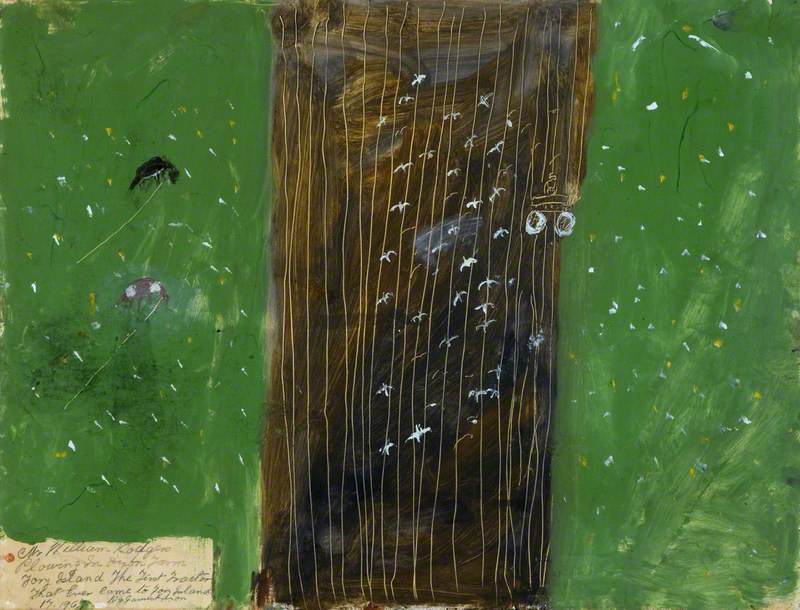

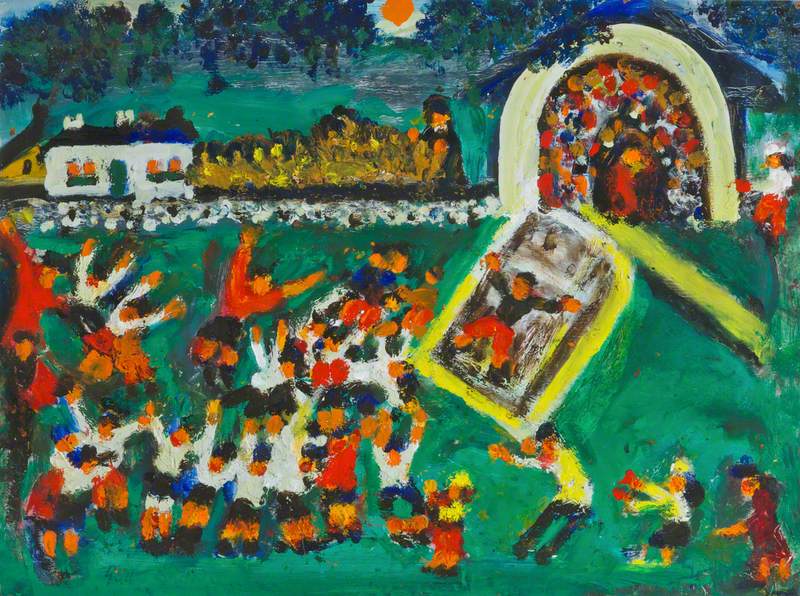

Like Wallis, Dixon's paintings often record momentous events in local history and the life of his community. In Mr William Rogers Ploughing in Dixon Farm, Tory Island: The First Tractor that Ever Came to Tory Island of 1967, the bird's-eye perspective places the artist in the position of an all-seeing eye, like a deity looking down over his kingdom and recording in detail the action at ground level. The tiny tractor seems to be almost engulfed by the surrounding landscape, and the birds and animals that share the pictorial plane command equal attention from the viewer. Indeed, the animals grazing to the left-hand side are as big, if not bigger than the tractor, and appear to be oblivious to it. One wonders if this is a subconscious trope, or whether the artist has intentionally created this non-hierarchal subject matter to suggest a coexistence between nature and machine.

British Minesweepers at Work between Tory Island and the Mainland is another painting that records the social history of Tory. Here Dixon depicts the naval minesweepers in black waters and treacherous weather conditions, performing their business in an ominous, uniform procession. The atmosphere of the painting is sombre in comparison to that of the previous work and one senses a dark veil cast by the impact of war on this community, despite its seclusion from the 'mainland' and Ireland's position as a neutral territory. Again, there is a successful tension between nature and the human element represented by the minesweepers.

British Minesweepers at Work between Tory Island and the Mainland

1965

James Dixon (1887–1970)

The text along the bottom of each of these paintings, often written on a small monochrome area almost like a plaque, is typical of the artist. Effectively it provides an explanation and reinforcement of the pictorial action, to leave the viewer in no doubt as to what is going on. It reminds us of how a child might add labels to their first drawings or paintings, as if uncertain about how their work might be perceived by the adult world.

Mr John Gallagher the Best Climber

1966

James Dixon (1887–1970)

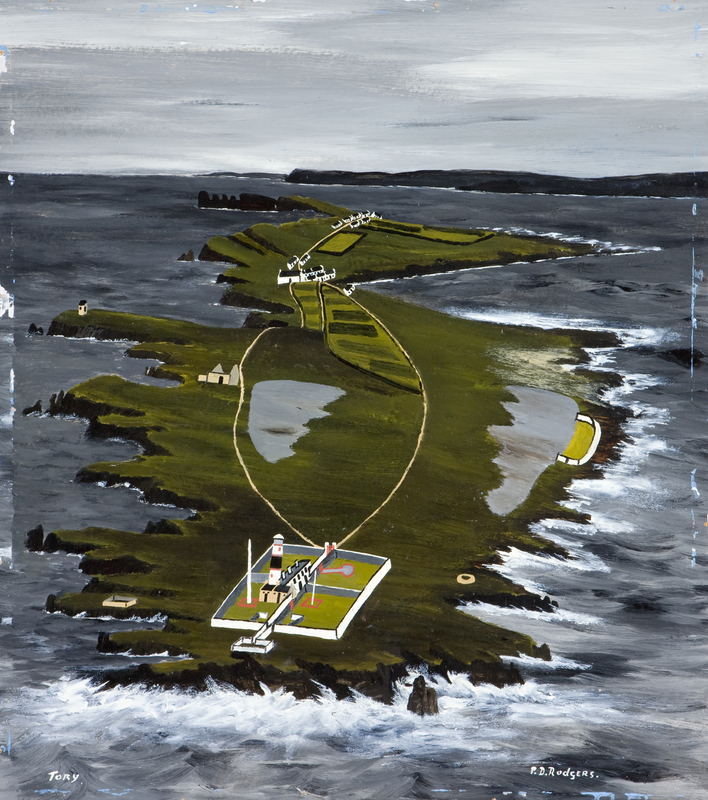

James Dixon was not the only Tory Islander encouraged to paint by Derek's presence. James' brother, John Dixon, is also known to have painted a small number of works, including Tory Island. There are similarities to James' approach to painting here, particularly in the way in which the boats and cliffs have been flattened, with no attempt made to depict their dimensionality. Arguably, however, this work seems to lack some of the confidence and assurance that comes through so strongly in James Dixon's art. One wonders whether this may be related to the fact that, unlike his brother, John had travelled extensively beyond the shores of Tory during his lifetime and, as an ironic consequence of this experience, falls just a little short of expressing himself in an authentically naïve manner.

In addition to James and John Dixon, a number of other islanders have become successful artists. Over the past sixty years, a school of painting has evolved as a fundamental part of the cultural fabric of Tory, of whom the former King of Tory, Patsy Dan Rodgers and his brother, Ruari Rodgers, are probably the best known.

Derek Hill donated Glebe House and much of his precious and varied art collection to the Irish State in 1981. As a result of this generosity, he was awarded honorary Irish citizenship in 1999. His adopted Donegal life constitutes, at least in part, a fascinating cultural exchange between fellow artists from starkly different backgrounds and with distinct artistic visions, but with a deep love of nature and a shared reverence for the austere, yet majestic landscape of Tory Island.

Jane Beattie, independent art market adviser and valuer

This story is supported by the Esme Mitchell Trust