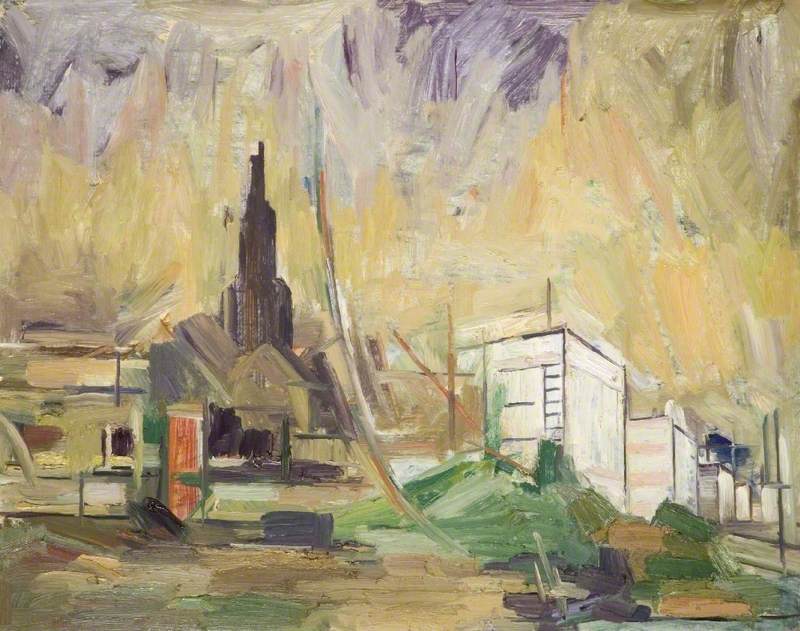

The towers in Heath Town, Wolverhampton are gone now, replaced by half-sized neon structures ten stories high instead of thirty. But when they were still standing, the grey Brutalist structures played host to the impromptu art gallery, Stairway to Fame. The Stairway to Fame swirled around the walls of the previously jaundiced stairwells of the tower blocks, every available inch of wall space a canvas for graffiti art. The space allowed for the expression of what was, and still largely is, an illegal activity.

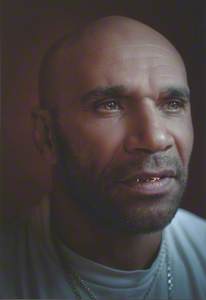

In the underground art world, it made this small, economically deprived area of a neglected post-industrial city something of a tourist destination. Front and centre of this movement was a man who would go from a Black Country council estate to the global fame of chart-topping records and James Bond movies – born Clifford Price, he would become better known by Goldie.

Goldie

Today, graffiti can be seen in every urban area up and down the UK, but that was obviously not always the case. It wasn't until the early 1980s that graffiti was imported from America and started to be seen more regularly on British streets. Its popularisation kick-started the eternal debate: is graffiti street art or antisocial behaviour? While graffiti is most often made illegally, street artist Banksy is today one of the most recognisable names in all of the art world, their pieces selling for millions of pounds at a time.

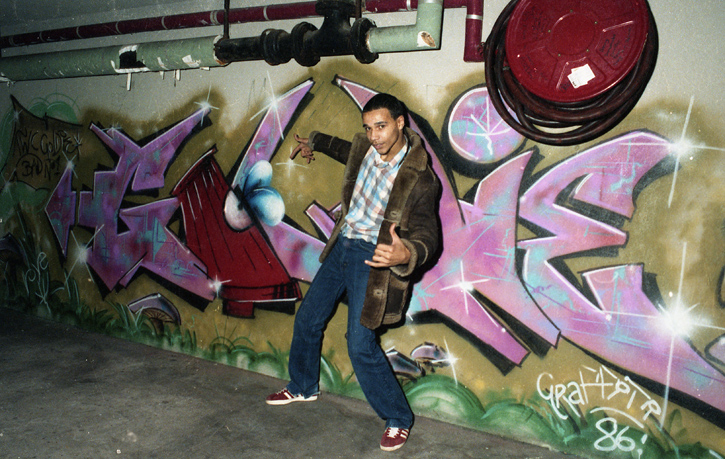

Because of its dubious legal status – and the relentless gentrification that has prompted high rises and urban spaces to mutate into austere and clinical places – much of the pioneering street art done by Goldie now only exists by way of photographs. Snapshots of his work, and the art of other early graffiti artists such as Chrome Angelz, Inkie and Robert Del Naja, offer an insight into the art and the artists behind them. The images depict young men and women expressing themselves outside of the mainstream that had rejected them, remarkably skilled with a stencil and a spray can.

Goldie did not have a steady upbringing. His youth was spent in a series of foster homes, and he was subject to horrifying physical, mental and racial abuse, and struggled in school. Yet an art teacher spotted his talent for drawing and inspired him to get into art. This led him to graffiti which eventually led him to conquer the world. But neither his art, nor hyperactive personality, betray the dark experiences he was exposed to.

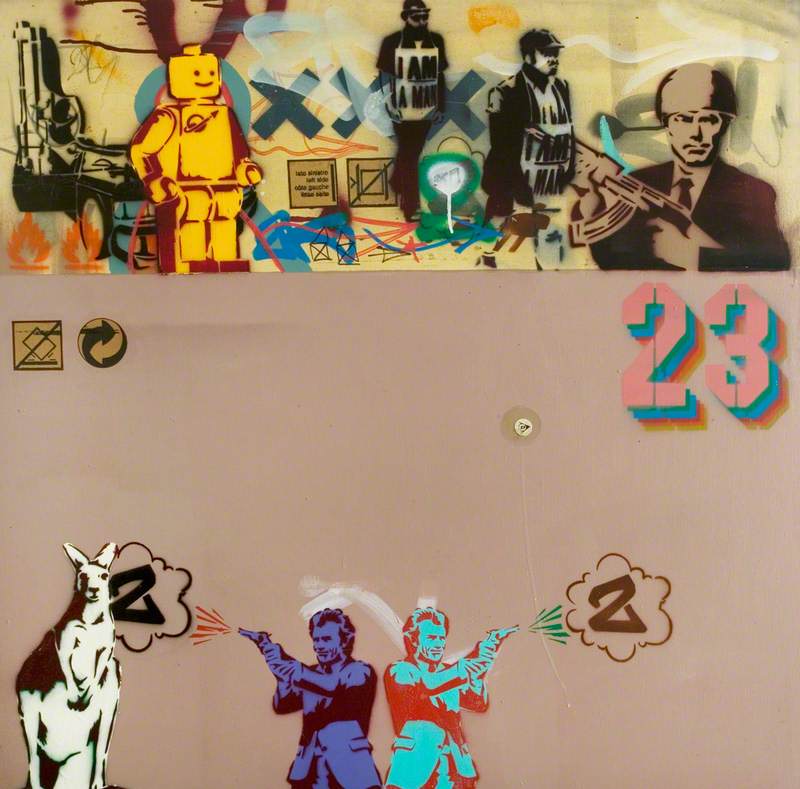

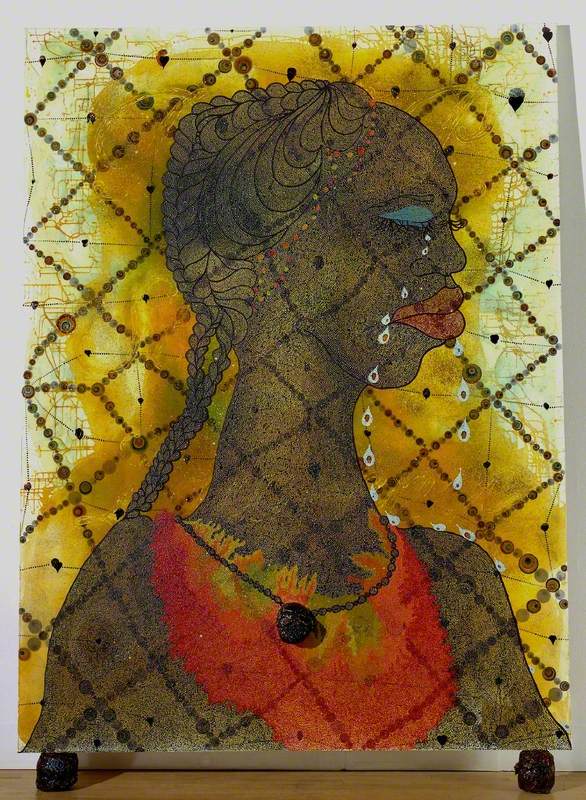

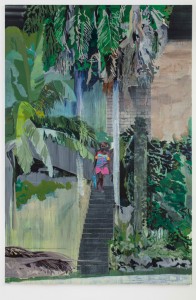

Cry From The Ghetto

wall art by Goldie (b.1965)

His graffiti is colourful and bombastic with wry humour – it's impossible not to look at something like the self-portrait of Cry from the Ghetto and see how Jamie Hewlett found inspiration for Gorillaz. Goldie's art quite literally brightened up the stairwells of Hawthorne House and the other high rises in the mid-1980s, with unemployment and hostile policing staples of living in Heath Town. The art pieces embody a wildly imaginative mind.

Tomorrow's World

wall art by Goldie (b.1965)

Tomorrow's World is a sci-fi utopia sprayed onto a stairwell. It illuminates silvers, blues and purples and appears inspired by Star Wars or Blade Runner with its sinister-looking robots and futuristic skyscrapers. It's notable that the futuristic skyscape could not look more different to the surroundings in which it was created. Hope and expression rose out of the grimy concrete.

Lost in Space

wall art by Goldie (b.1965)

This theme of utopian futurism was evident in much of Goldie's early work: a piece entitled Lost in Space sprayed on the block of Heath Town shops depicted an astronaut with his eyes blacked out except for a shimmer in the right one. It's an eerie piece, virtuoso in technique and a haunting depiction of man's search into the darkness of the galaxy. These themes found a climax with one of Goldie's earliest legal, professional commissions, Future World Machines. Done on canvas for an exhibition at Wolverhampton Art Gallery, it was a display of vivid imagination, of prescience for the world that awaited us.

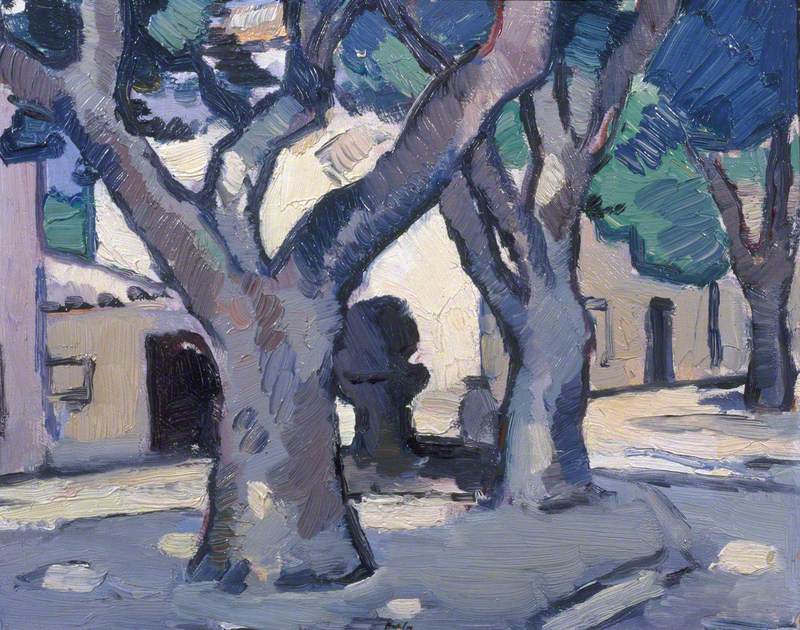

Future World Machines

wall art by Goldie (b.1965)

Painted in 1986, the blues and silvers of the piece present an autonomous society at the mercy of machine, not unlike the 2021 version of society with its development of artificial intelligence, facial recognition and corporations preferring robotics to humans in the manufacturing chain. In the centre of the piece is the word 'world' in a blur of pink, red and blue block capitals. The lettering is seemingly in a rush to be anywhere but where it actually is, a nod to the rapid technological advancements the human race experienced in the late twentieth century. Next to the word lies what could be a human being or an android (or a hybrid of both) strapped to a painful-looking steel chair, an image that would become famous at the end of the decade with the release of the Arnold Schwarzenegger classic movie Total Recall. But Goldie, with Future World Machines, captures the same unease around technology and a rapidly changing world. The Renaissance has the Mona Lisa, Romanticism has Liberty Leading the People and graffiti has Future World Machines.

Critics of graffiti malign it for lacking substance but the truth is the opposite. Regardless of the aesthetics and expression of the art, graffiti tagging is a fundamentally political act. It defies the law and property ownership and critiques the idea of public space. The work of Banksy is overtly political, Bristolian Robert Del Naja (who would later co-found the band Massive Attack) helped lead the march in Hyde Park against the war in Iraq, and there are often recurring themes to spot when visiting street art sites across the UK: you will almost always see a mural of Muhammad Ali, references to the pioneers of hip hop like Public Enemy and a celebration of everything outsider and underground. This politicisation descends directly from Goldie, who wasn't just spraying shapes and tagging his name around a council estate – he was painting what he thought of the world around him and, in doing so, defined graffiti art as limitless in its potential and capacity for ideas.

Goldie brought forth the graffiti revolution in the UK and, with that, eroded the class barriers and snobbery of the art world. All you needed was a spray can, a blank wall and a quick pair of legs in case the police came calling. With the rise of graffiti, art became increasingly democratised and more relatable – you have to go to the Tate or the V&A to see fine art but to see graffiti you just need to walk to school or catch the bus. The brilliance of graffiti is all you need to is open your eyes and see it – on skate parks, subways, shuttered high street shops. There was once a time where you could walk through the doors of Hawthorne House and see Goldie's name sprayed in bright pink across the lobby. It has been long scrubbed away but he and his impact on graffiti art and British culture won't be forgotten.

Sam Moore, freelance writer

More images of the UK in the 1980s can be seen on Martin Jones' UK Hip Hop Archives Project on Facebook