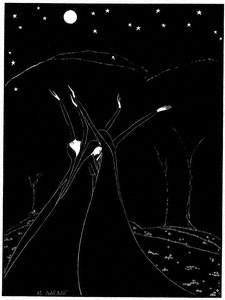

Al Aaraaf was the pen name chosen by artist, sculptor and poet Hannah Frank (1908–2008), borrowed from a poem by Edgar Allen Poe. Two years before her death she told me: 'Al Aaraaf was a star that appeared in the heavens. In a few nights it grew brighter than Jupiter and Venus, then it disappeared and was never seen again.'

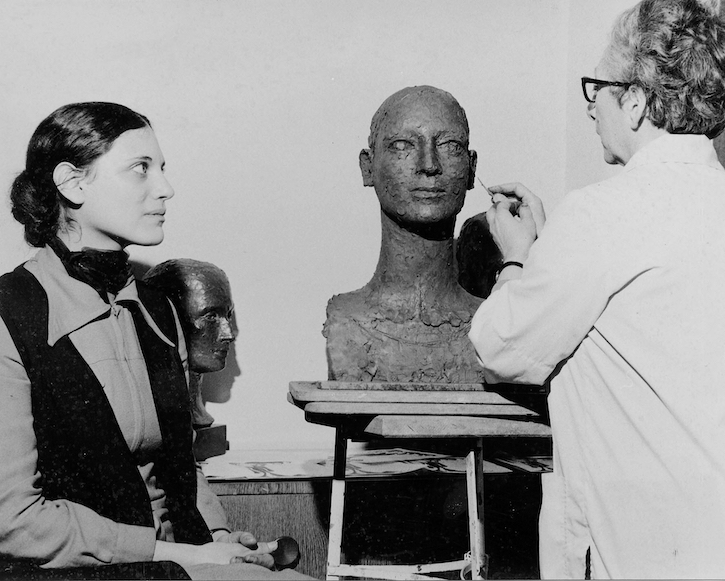

Hannah Frank making 'Woman and Trees'

photograph

Thanks to the tireless work of her niece Fiona Frank, the reality of Hannah's legacy is quite different. Her distinctive Art Nouveau-style monochrome drawings and bronze sculptures have been celebrated at the Scottish Parliament, featured on Woman's Hour, and exhibited at the National Galleries of Scotland and more.

With another International Women's Day recently passed, it has struck me anew how remarkable is the story of Hannah's work becoming known and cherished, when it might have languished in attics and cupboards. And most of all, 15 years on, I am reminded how fortunate I was to meet this quietly rambunctious character and to have the privilege of filming her before her death in 2008, aged 100.

In the run-up to Hannah's milestone year, Fiona committed to a five-year plan – a personal mission to save her aunt from obscurity, on a shoestring budget. A chance encounter with Fiona led to me making a film to accompany her centenary exhibition. The exhibition toured various venues in the UK and USA before opening at Glasgow University Chapel on the centenary, where Hannah Frank: The Spark Divine was premiered.

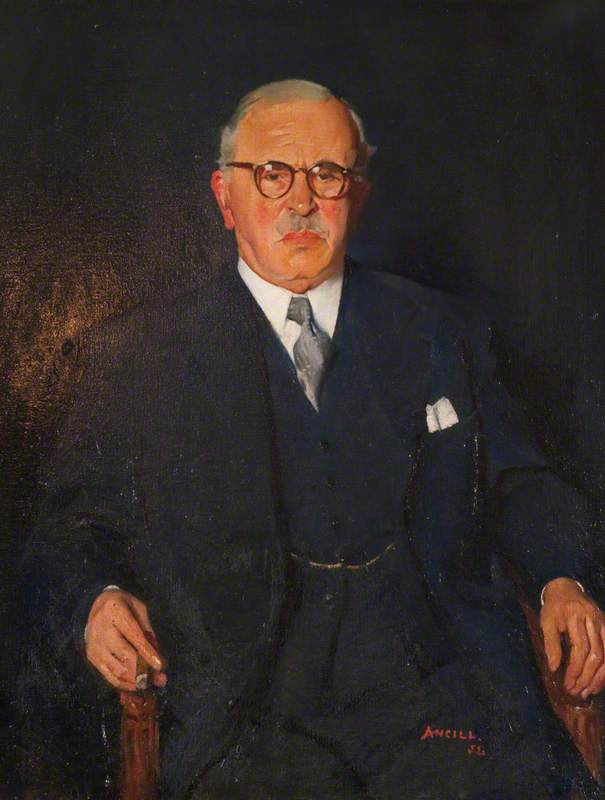

Hannah was born to Charles Frank and Miriam Lipetz, both immigrants who had landed in Glasgow. Charles had fled persecution in Russia and settled in the Laurieston district of the Gorbals. The year before Hannah was born, he opened a shop at 67 Saltmarket, and subsequently a Queen Street premises in the city centre for the design, sale and repair of photographic and scientific instruments.

Young Hannah with her mother, Miriam Lipetz

photograph by unknown

As Hannah grew up, both shops regularly exhibited her drawings and sculptures. Charles Frank Ltd was reputed as one of the best photographic centres in the city, and Hannah's work became part of the Glasgow subconscious, imaginatively associated in people's memories with telescopes and optical equipment.

'If they would leave the choice to me, I think I know what I would be:

To be an artist my desire. I'd paint weird gnomes and ne'er would tire.'

This poem by a very young Hannah shows her vocation was always clear, and she pursued this dream with conviction. Much fed into her artistic practice, inspiring, informing and cultivating it. She began creating her monochrome drawings in 1925 at the age of 17. From 1927 to 1930 she studied Latin and moral philosophy at the University of Glasgow whilst attending evening classes at the Glasgow School of Art.

Succeeding in these enrolments was no mean feat as a Jewish woman, there being very few women at the university, and the art school not accepting her of her own merit. Instead, her mother had to request a personal recommendation from a neighbour, Baillie Drummond – a civic officer in the local government of Scotland.

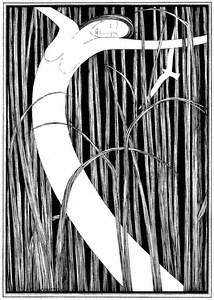

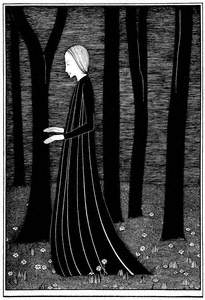

Between 1927 and 1932, Hannah contributed drawings to almost every edition of the Glasgow University Magazine under her pen name of Al Aaraaf, which provided a regular audience and opportunity to develop her style. An earlier illustrative style evolved into the intricate flowing lines and mastery of light and dark of her monochrome drawings, which have drawn comparisons with the work of Aubrey Beardsley and Jessie King.

She also had a brief spell of printmaking and wood engraving. From 1930 to 1950 her drawings were exhibited regularly at the Royal Glasgow Institute of the Fine Arts. In the early 1950s, she developed a passion for bronze sculpture, training under Benno Schotz. She took it up entirely to improve the anatomy in her drawings, but soon fell under the spell of this art form, never returning to drawing.

Hannah Frank sculpting a likeness of Jan Bruml

photograph by unknown

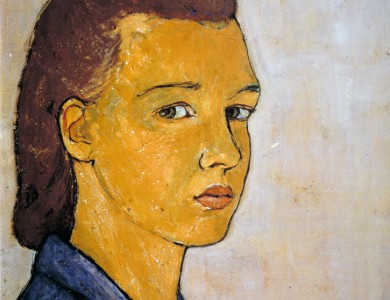

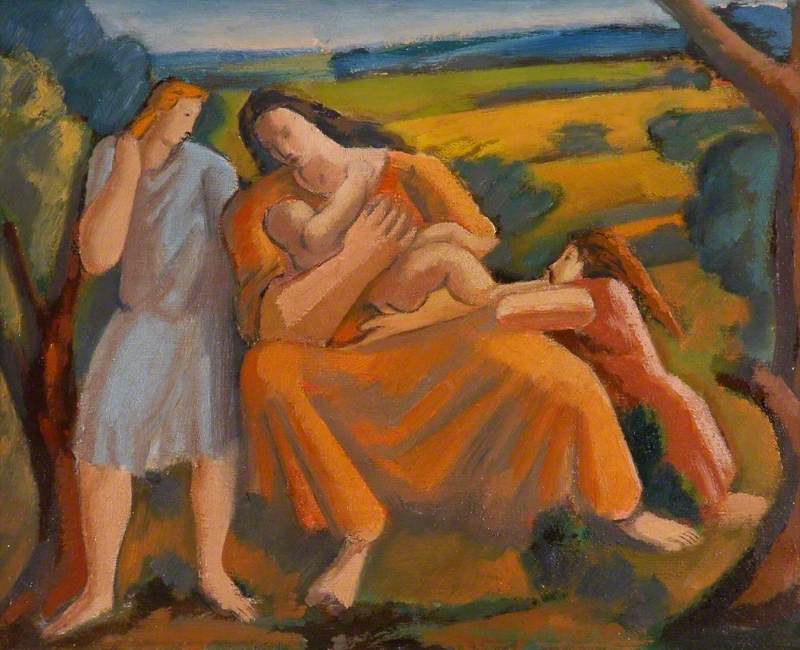

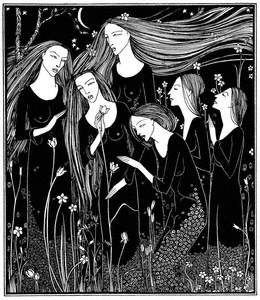

Alongside this formal study, stoking her creativity was the rich seam of interwar Glasgow Jewish life. She was particularly inspired by the women she lived with and amongst, often drawing sketches or spending hours on detailed portraits of her peers. Women feature heavily in her monochrome drawings and sculptures – joyous, pensive, intimate.

She said: 'I was much better at drawing women than men, and men didn't interest me particularly ... I didn't have any ideas about men's anatomy ... Women I quite liked, I was a woman, and it wasn't a mystery to me. Women are much more inviting to draw and to sculpt.'

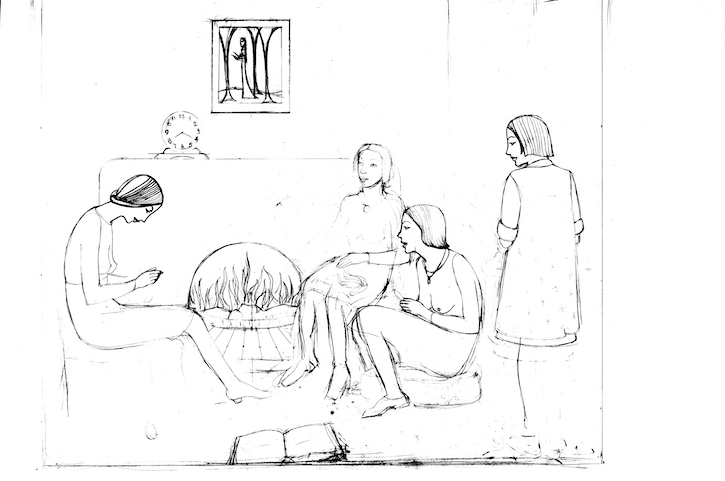

The Fireside

1939, unfinished sketch by Hannah Frank (1908–2008)

Hannah moved between the social and the solitary. One of her most beautiful and intimate drawings playfully encapsulates these two states, featuring a visual cameo. In The Fireside (1939), a gaggle of girlfriends chat beside the fire beneath a reproduction of Hannah's own 1931 pen and ink drawing Woman and Trees, which hangs above the mantlepiece.

In her solitary moments, she was a keen reader – too keen, according to her mother. She would sit in the attic of the family home and dive for hours into tomes such as the complete works of Shakespeare, or the Bible, whose poetry she found deeply moving.

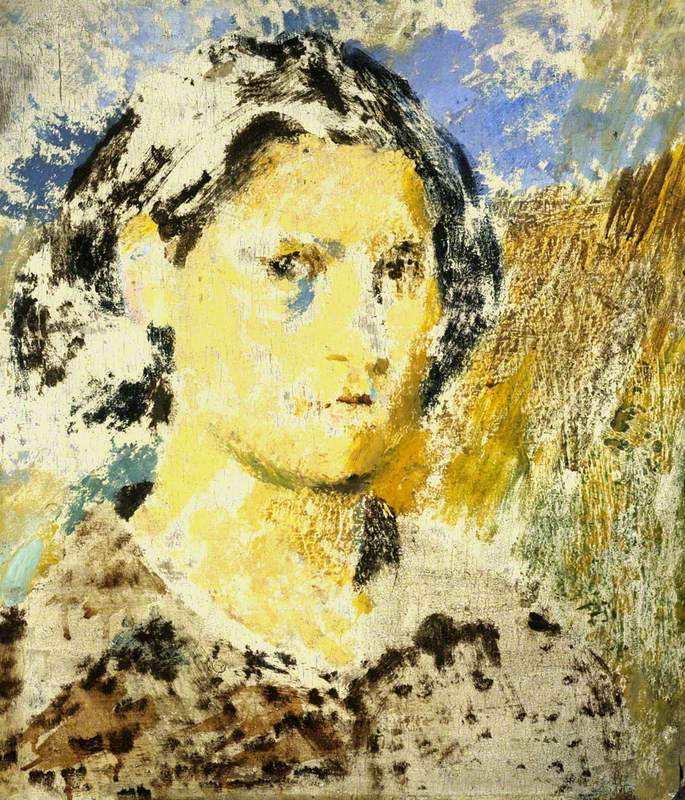

Untitled (the family home at Dixon Avenue)

1926, watercolour by Hannah Frank (1908–2008)

As a young woman, she was also fun-loving, gregarious and clearly enjoyed exploring her emotional landscape. She was in and out of friends' houses, always with her sketchbook, and attended summer camps with the Glasgow Jewish Students' Society.

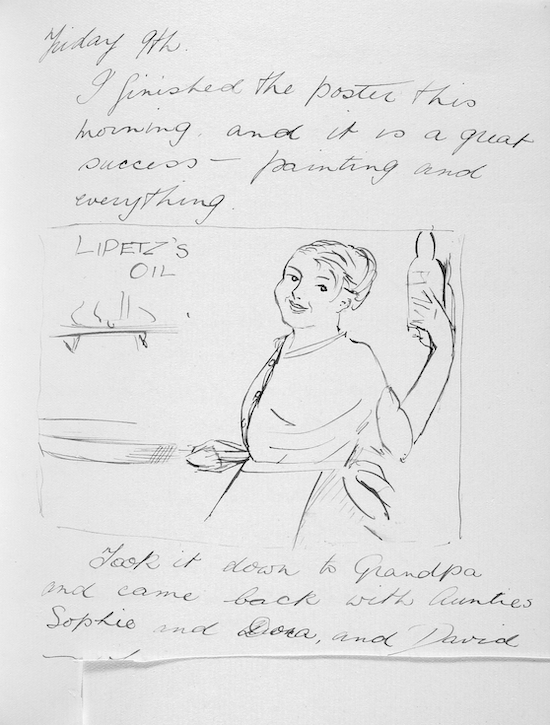

A page from Hannah Frank's diary

A lifelong diarist, some of her earlier volumes used various means – the Greek alphabet, removing words, or cutting out whole pages – to maintain the privacy of her heart. When we spoke to her for the film, she admitted to having had 'crushes' on men and women both, which had driven some of her choices in life.

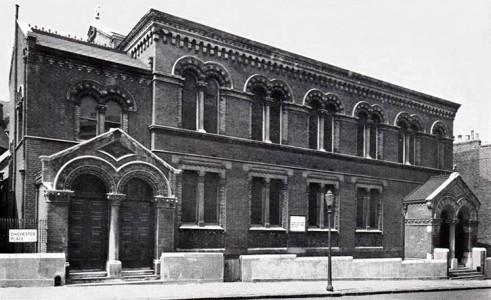

She eventually met Lionel Levy, who she loved and remained married to until he died. He supported her in keeping up her artistic practice as a married woman, which was not a given at the time. These diaries, along with letters and documents, are now housed at the Scottish Jewish Archives at Garnethill Synagogue, catalogued as the HFLLC – Hannah Frank and Lionel Levy collection. The entries are a rare and fascinating glimpse into Glasgow Jewish domestic life and the tracking of her career, and form the backbone of the film.

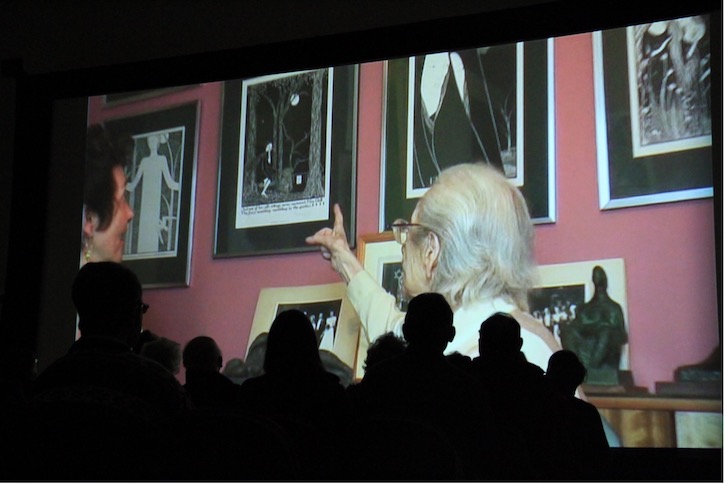

Film screening at Shetland Museum and Archives

Hannah lived out her later years in a Jewish care home in Newton Mearns, on the outskirts of Glasgow. I first met her there in 2006, on a recce for the film. Her work adorned the care home walls and her sculptures were displayed in niches in the atrium. As we entered her tiny room – all bed and framed Hannah Frank prints – a large bronze sculpture sat by her window, repurposed as a hat stand.

It was Chanukah, and Fiona was invited to light the menorah at the communal dinner. That day, in conversation with Fiona, Hannah was lively, reminiscent and opinionated, an artist proud of her life's work, which I knew at 98 was not to be taken for granted. I seized the moment, barely finding a corner in her cramped quarters to set up the tripod.

Though her short-term memory was suffering, she was lucid about the past and recited whole passages of poetry, given the first few words. We returned in 2007 on her 99th birthday to shoot an interview proper, but we found Hannah low in energy and far less lucid. I realised then that the recce footage would have to be our source material. One lookalike great-niece played the younger Hannah, while another, an actress, read the diary entries.

Hannah Frank with Fiona Frank at the centenary celebration in Glasgow

At the centenary exhibition and celebration at Glasgow University Chapel, she bounced back. Entering the room full of guests in a wheelchair, she was like a twilight Frida Kahlo: magnetic; the star burning brightly. Renowned sculptor Andy Scott was the special guest and proffered a personal gift – a print of one of his sculptures – which she unwrapped on the spot. 'Oh,' said Hannah with a glint in her eye. 'I thought it was a box of chocolates.' Andy said of Hannah that she was tiny but had the handshake of a stonemason.

Hannah's death in 2008 was announced on BBC Radio Scotland. In 2015–2016 her work was selected for the National Galleries of Scotland exhibition 'Modern Scottish Women: Painters and Sculptors 1885–1965'. The five-year plan not only worked, but has grown legs of its own.

Sarah Thomas, writer and filmmaker

This content was supported by Creative Scotland