'I was trying to open up a territory for desire, how to depict desire and physical sensation and pleasure. And given that one's experience of that is through the body, it seemed that the body was central to the project,' explained the artist Helen Chadwick (1953–1996) in an interview. Her words speak to the core concerns of her artistic practice, which embraced the corporeal.

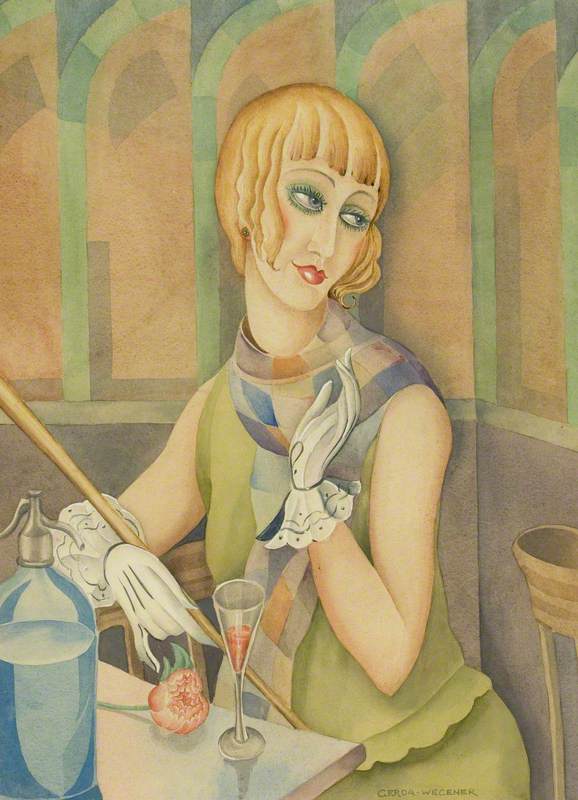

Portrait of Helen Chadwick

Unafraid of strong odours and sludge, Chadwick is known for employing a vast range of materials in surprising ways, incorporating bodily fluids, meat, flowers, chocolate, and compost into her works. Through her unconventional approach to artmaking, Chadwick quickly established herself as a leading figure amongst Britain's post-war avant-garde, becoming one of the first women artists to be nominated for the Turner Prize.

Although she was widely exhibited during her lifetime, attention to her work has declined following her unexpected death at the age of 42. A multidisciplinary artist who embraced risk and experimentation, Chadwick left behind a rich body of work that is ripe for rediscovery by new generations of art enthusiasts.

Born in Croydon to a Greek mother and British father, Chadwick expressed profound curiosity in the world around her from a young age, and she would allegedly spend childhood afternoons peering into the lens of her microscope. Though she initially planned to study archaeology and anthropology, Chadwick applied to art school at the last minute, a decision that sealed her fate. While her love of artmaking ultimately prevailed, her preoccupation with materiality and human culture persisted, materialising in the diverse works she produced.

Early projects from her time as a student express a feminist perspective steeped in criticality and humour. Her mixed-media work Menstrual Piece (1976) and performance Domestic Sanitation (1976) consider how gender roles are reinforced – and contested – through architectural space and clothing, respectively.

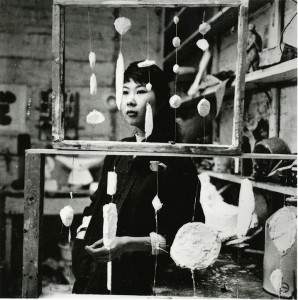

In the Kitchen (fridge)

1977, installation by Helen Chadwick (1953–1996)

For her MA graduation project, In the Kitchen (1977), Chadwick created wearable sculptures representing household appliances, which she fabricated from metal frames and soft PVC 'skins'. These objects doubled as costumes that Chadwick and her classmates wore during performances for live audiences and the camera.

By merging women's bodies with kitchen equipment, Chadwick's work satirises the domestic roles women were expected to 'naturally' inhabit. Constricted by the metal structures, the women's bodies become machinic, while the objects in turn become bodily, with the stovetop mirroring breasts and the door of the washer-spin dryer recalling a pregnant belly. This attention to intersections between the physical, social, and representational would go on to define her practice.

Following graduation, Chadwick began teaching at art schools across London, including Goldsmiths, where she worked alongside fellow instructors Mark Wallinger, Michael Craig-Martin, and Judith Cowan. While there, she mentored a younger generation of artists, including members of the Young British Artists. Among her students, she was known for her sharp intellect and sleek haircuts. Her influence can be felt in Sarah Lucas' use of meat and intestinal forms and Anya Gallaccio's work with chocolate and flowers.

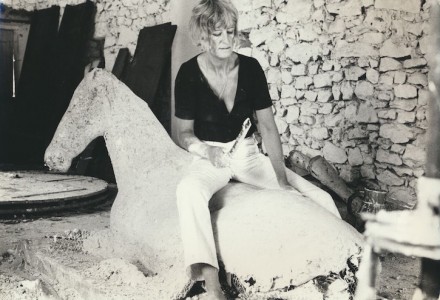

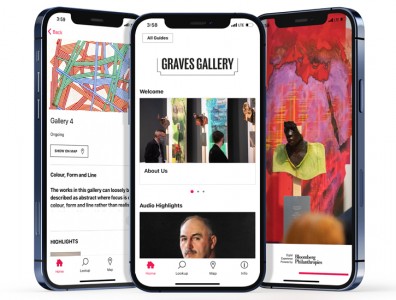

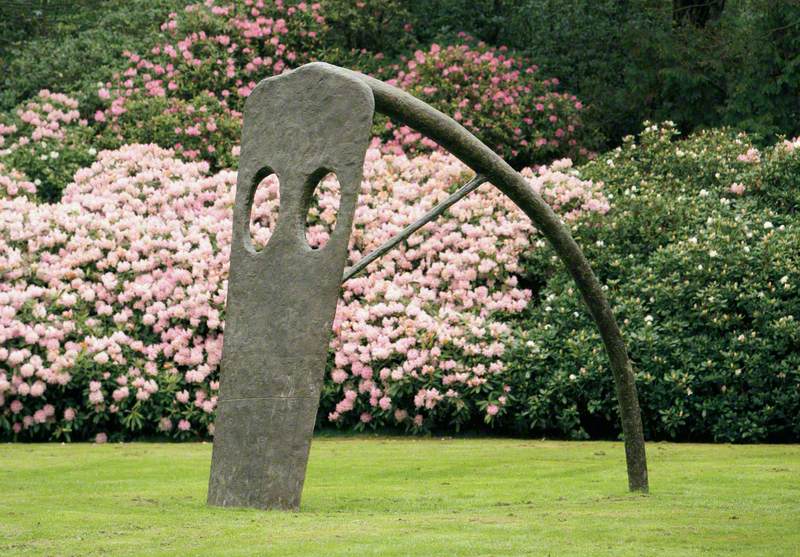

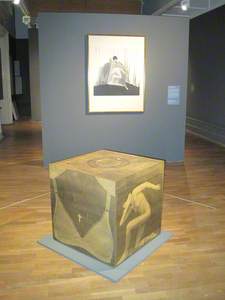

After a self-described 'sociological phase' in her practice, Chadwick felt the urge to begin a more autobiographical project recentring her own body and experiences. In Ego Geometria Sum (1982–1983), Chadwick constructed a series of ten wooden sculptures each portraying a different stage of life, represented by geometric forms printed with photographic images. Ego Geometria Sum IV: Boat, Age 2 Years is a triangular boat, age nine is a piano, age eleven a horse, and high school a cube.

Ego Geometria Sum VIII: The Horse Age 11

1982–1983

Helen Chadwick

Created when she was 30, the series of sculptures traces key milestones in the artist's development during her three decades of life. According to Chadwick, the works 'offer evidence of the passage of time, the effects and constraining influence of socialisation.'

At times, Chadwick's work inspired controversy due to her non-traditional choice of materials and subject matter. Even certain feminists were uneasy with Chadwick's celebratory representations of her nude body, and suggested they reproduced sexist stereotypes. These criticisms rankled Chadwick, as she was keenly aware of the politics of the 'male gaze' and felt her work presented women as subjects, rather than objects of desire.

Ego Geometria Sum IV: Boat, Age 2 Years

1983

Helen Chadwick

However, untroubled by her detractors, she continued to make work exploring her own body, never compromising her singular artistic vision. Her efforts were rewarded in 1986, when the Institute of Contemporary Arts hosted her first major solo exhibition 'Of Mutability'. Her impressive installations featuring a pool-like collage of blue photocopies, gold spherical sculptures, and a tower of rotting vegetables garnered Chadwick considerable attention. The following year she was recognised with a nomination for the Turner Prize.

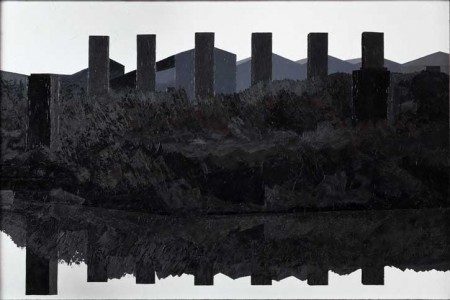

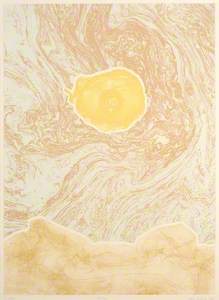

Anatoli

(King's Fund Prints; edition 69/250) 1989

Helen Chadwick

As her work began to receive greater acclaim, Chadwick also took on commissions. She made the print Anatoli (1989) for the King's Fund Hospital Project. Named after a town in her mother's native Greece, Anatoli appears to depict a sun over a jagged mountaintop, but also visually recalls her Polaroid photograph Meat Abstract No. 1 (1989), part of a larger series depicting animal meats with everyday items such as lightbulbs and textiles. She aimed to create complexity through juxtaposition of objects not normally pictured together, which inspired unexpected responses in her viewers and disrupted obvious readings of her work.

Meat Abstract No. 1 (Variation)

1989, polarioid by Helen Chadwick (1953–1996)

Many of Chadwick's works from this time explore the tension between theoretical ideas and fleshy physicality, as exemplified by the wall sculpture The Philosopher's Fear of Flesh (1989), which features a hairy naval enclosed in an eight-shaped frame reminiscent of the infinity symbol.

The Philosopher's Fear of Flesh No. 1

1989

Helen Chadwick (1953–1996)

However, by the end of the 1980s, Chadwick began to shift away from focusing on the exterior of the body to reflecting on its interior through engagement with materials like embryos and cellular tissue.

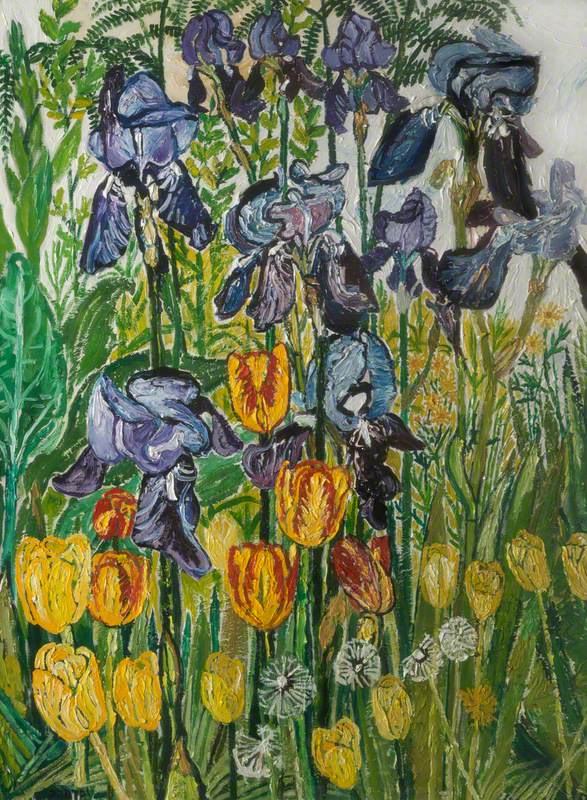

Other works, such the wall installation Eat Me (1991), examine the blurry boundary between the real and artificial. Here, a row of eye-shaped light boxes illuminate photos of bluebells clustered around a circular pool of dark liquid. Directly above them, another light box resembling a lemon depicts a collection of yellow flowers topped with an oyster. Together, these compositions reference both the edible and sexual, while also drawing attention to photography's ability to manipulate perception.

Continuing her investigation into connections between plant life and human bodies, Chadwick created her iconic work Piss Flowers (1991–1992/2016) by urinating in the snow with her partner David Notarius, then casting the depressions made by the hot liquid in plaster, and later in bronze.

When inverted through the casting process, Chadwick's long stream of urine produced a phallic rod resembling a stamen, while Notarius's lighter sprinkling created small bumps reminiscent of labial petals. Though earlier in her career Chadwick had been criticised for how she represented women's bodies, with Piss Flowers she challenges the gender binary system itself.

A poem titled Piss Posy that she wrote in response to the work emphasises its whimsical irreverence: 'Linnaeus what would you say, how define such wanton play, vaginal towers, with male skirt, gender-bending water sport?'

Chadwick's illustrious career was unfortunately cut short a few years later by her premature death by a heart attack. A dedicated researcher, she left behind stacks of notebooks and a large collection of annotated books. She meticulously documented her artistic process, resulting in an extensive archive now housed at the Henry Moore Institute. With this trove of materials available to researchers and a renewed public interest in second-wave feminist art, Chadwick's work may finally receive the attention it deserves.

Lexington Davis, PhD candidate at the University of St Andrews