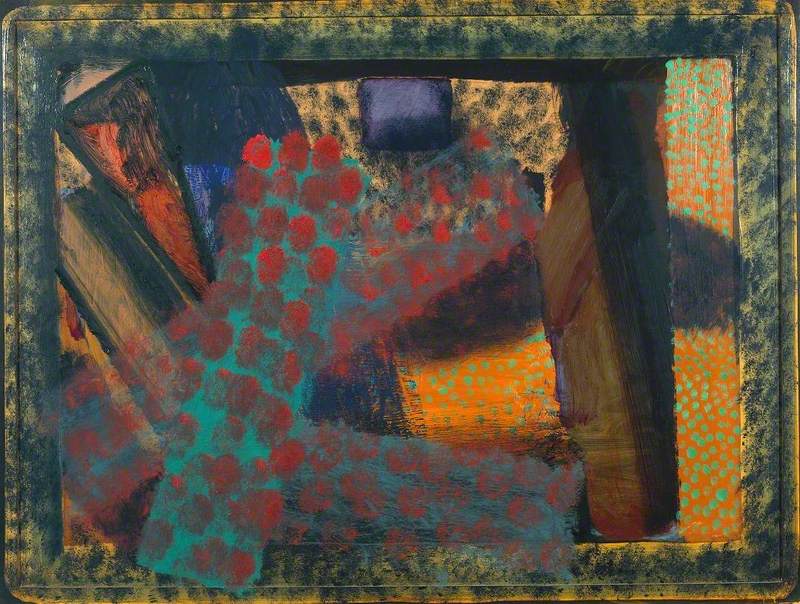

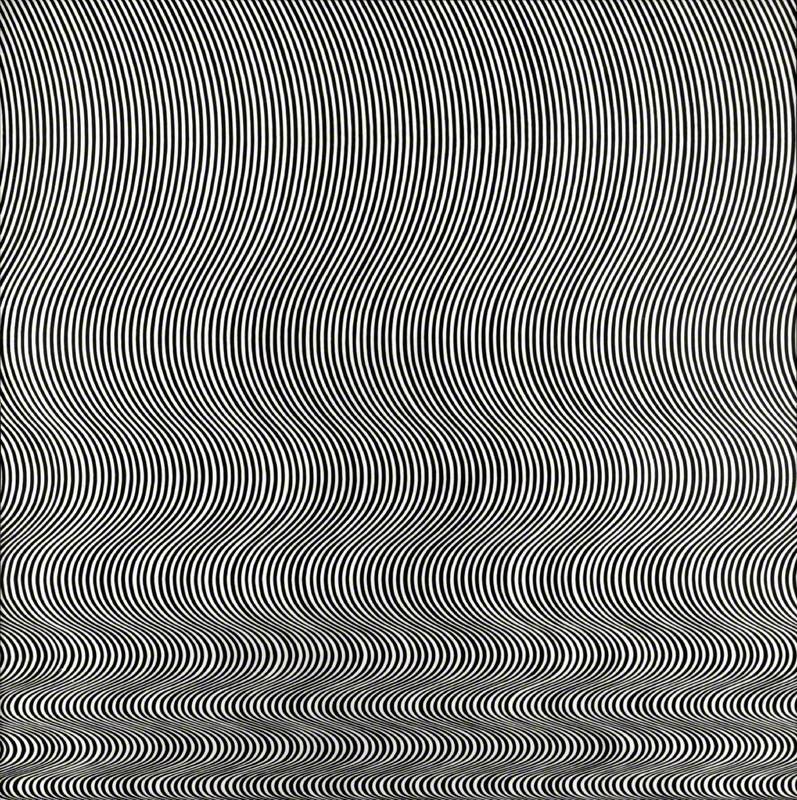

This is one of Howard Hodgkin’s largest paintings, measuring 164 x 179.5 cm, but you wouldn’t necessarily guess in reproduction.

The blocks of colour, the heavy dark stripe and the characteristic ‘frame’ of blue, seem to be constituted of single brush strokes. The effect of the larger paintings, as the critic Andrew Graham-Dixon has noted, is of being dwarfed by a miniature; there is something ineluctably immersive about the abstracted forms. Because of this abstraction and the scale, (unusual for Hodgkin: most of his paintings are smaller, more intimate, ‘mantelpiece’-scale) this and others of his large works seem to have an affinity to 1950s and 1960s Abstract Expressionism: the immersive colour-field paintings of Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, or the painterly simplifications of Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline.

It’s a comparison frequently noted by critics, and not without evidence. Hodgkin made a trip to New York in 1948, the year before he began studying at Camberwell School of Art, during the first flush of Abstract Expressionism. He also saw the famous travelling Museum of Modern Art exhibitions Abstract Expressionism and New American Painting in London in 1956 and 1959, and has described them as a ‘tidal wave’, struck by the scale of the works he saw: ‘they taught us that more is more,’ he told Alan Woods in 1988.

'More is more'; it’s a simple phrase, but the mores that characterise Abstract Expressionism and Hodgkin’s work are different, even if their modes of abstraction, technique and even concern with colour might seem ostensibly similar.

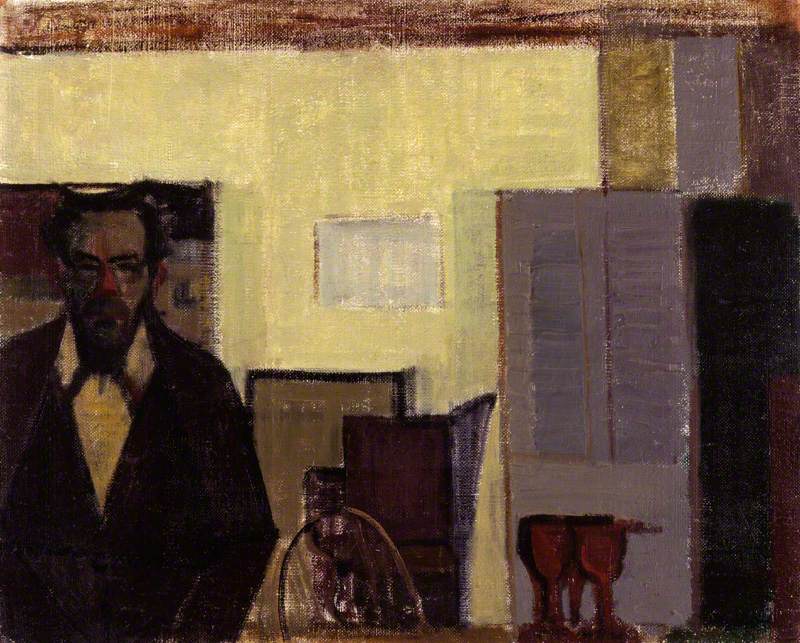

More is more. When we imagine the Abstract Expressionists, we imagine men standing alert, brush in hand, in front of enormous canvases, absorbed in their work; men (and it was mainly men) devoted in an almost religious way to the canvas, to paint. The use of words like ‘myth’ and ‘mysticism’ by both artists and critics to describe the group gives us some idea of the quasi-divine aura that the works produced. The critic Harold Rosenberg – who preferred the term ‘action-painting’ to ‘Abstract Expressionism’, because of its association with the pure, intensely personal and reclusive image of the painter dedicated not to representation, but to the simple act of painting – saw this period as a complete break from tradition, a kind of rupture without precedent; visionary and transformative.

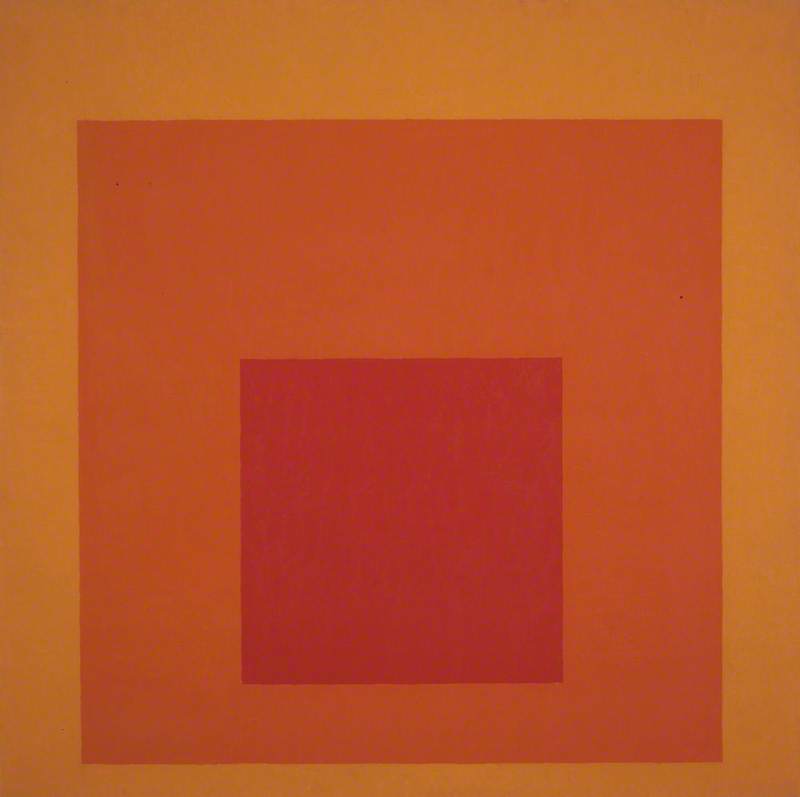

Rosenberg’s contemporary and bitter rival, critic Clement Greenberg, saw Abstract Expressionism in different terms; as the next stage in the historical progression away from other arts such as sculpture, a means by which the painting isolated what made painting unique – paint and canvas. Sculpture is entirely form, so painting had discarded any concern with representing form.

As different as Rosenberg’s and Greenberg’s accounts are – and they are, of course, only sketchily described here – they still both support this image of the artist as absorbed in his materials, striving for a ‘pure’ art. Hodgkin’s work, and his personality, seems very different. For a start, whilst artists like Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock quickly abandoned naming their paintings and gave them numbers or no name at all (or, at least, simply named the colours used in them), Hodgkin’s works’ names testify to personal experience, to a life outside the studio, the paint, the action. Many of them describe particular situations (like Dinner at Smith Square), places (In a Hotel Garden) or people (Memories of Max). They also generally take many years to paint and yet show few signs of revision or mistakes, as though Hodgkin has given them an enormous amount time and space; it’s like he’s painted a few strokes, gone for a walk outside, moved onto another work for a while, lived a life beyond them. This is a far cry from the trance-like intensity we often imagine, and are encouraged to imagine, how abstract painters work.

More is more. The concept of a sort of divinity or mythology can also be seen in the works themselves. A good example might be the art of Mark Rothko, whose paintings might be said to resemble Hodgkin’s, in their shared use of bands of colour, and their frequent use of borders and squarer shapes that draw our attention to the shape of the canvas or wooden board on which the work is painted. They are also quite similar in just how startling the colours they use are: Hodgkin’s brave juxtaposition of bands of light and dark, and Rothko’s luminescent pastel shades or brooding dark tones.

Art historian Robert Rosenblum places Rothko in a tradition that goes back to the likes of Turner, many of whose landscapes become masses of cloud, sea and land; churning colours showing an image of nature’s sublime, and indicating a god-like presence. The awesome power of Turner’s landscapes is certainly present in Rothko’s work; he was, for instance, commissioned to design murals for an interdenominational chapel in Houston, Texas in 1964. Rothko’s compositions are, therefore, not simply an expression of his own psyche, but also a product of a tradition of Western art which deals with secular divinity, which references the power of the altarpiece.

Hodgkin could definitely be considered part of this tradition, an heir to Turner’s powerful visions of landscape. The feeling of suspension, of the tense relationship between dark and light, that we get from Rothko’s canvases we definitely also get in Rain. In the presence of the dark, heavy band at the top that seems to represent a raincloud, but the absence of any other indication of rain, like we’re suspended forever in the moments just before a storm, in the vertical stripes of orange and pink which challenge the heaviness of the cloud and frame.

The difference is that, whilst the tension in Rothko’s paintings come from the relationships of colours alone, much of the tension we experience in Rain is from the fact that we can say that represents a raincloud/a hill/grass. We’re caught somewhere between abstraction and representation, in a way much closer to Turner (though his colours may be more muted, his subject more readily identifiable) than Rothko. It’s also a matter of scale: Rothko’s huge paintings easily envelope us, whereas even a larger Hodgkin painting like this still seems to reference smaller forms: we’re still in a realm closer to mantelpiece than altarpiece.

And yet, for all the Abstract Expressionists’ concerns with the universal, with psychological, religious or mystical experience, Hodgkin’s paintings have a profound effect on their audience. Only a cursory internet search will reveal an enormous body of reverential writing on Hodgkin, on how deeply his paintings chime with viewers’ experiences. When Rain appeared in the 2002 exhibition Howard Hodgkin: Large Paintings 1984–2002 at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Hodgkin decided that walls be painted a dark blue, and one can imagine the paintings shining like portals against the background. Compare this to how the Abstract Expressionists responded to the stark, white austerity of Modernist architecture; it’s not so much that Hodgkin’s work is more domestic, but rather that, acting like windows into a bright, idiosyncratic world, they inspire us to think about Hodgkin’s experiences, invite us to search for how they express our own experiences of life. The mores which govern his work are emotional and personal as well as artistic. That, in many ways, is the triumph of Hodgkin’s abstraction: they are as much a mirror of our lives as a product of his.

Benedict Hawkins, Cambridge University graduate