The Scottish artist Beatrice M. L. Huntington (1889–1988) enjoyed a long and varied career as a painter and is best known for her insightful portraits, characterised by a strong sense of design and an intuitive use of colour.

Image credit: William Syson Foundation

Beatrice Huntington painting

c.1920, unknown photographer

Her approach to painting was ever-evolving: throughout her long and fascinating life, which spanned a century and bore witness to the advent of the modern era, she remained indefatigably committed to her development as an artist and to 'containing and realising the big-ness of it all', as she herself described it in a letter to a friend in 1977, when at the age of 88 she was still refining her approach to form and colour.

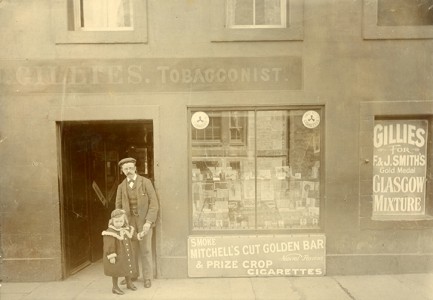

The daughter of an eminent St Andrews doctor, Beatrice grew up in affluent surroundings – an imposing townhouse on St Andrews South Street both her father's surgery and the family home. A precocious talent for both music and art led her, perhaps unusually for a girl at that time, to pursue her studies abroad. In 1906, the year she turned 17, she went to Paris to study drawing and painting and in 1911, after an evidently successful formative period in Paris, she continued her studies in Munich, attending a private art school where she apparently flourished.

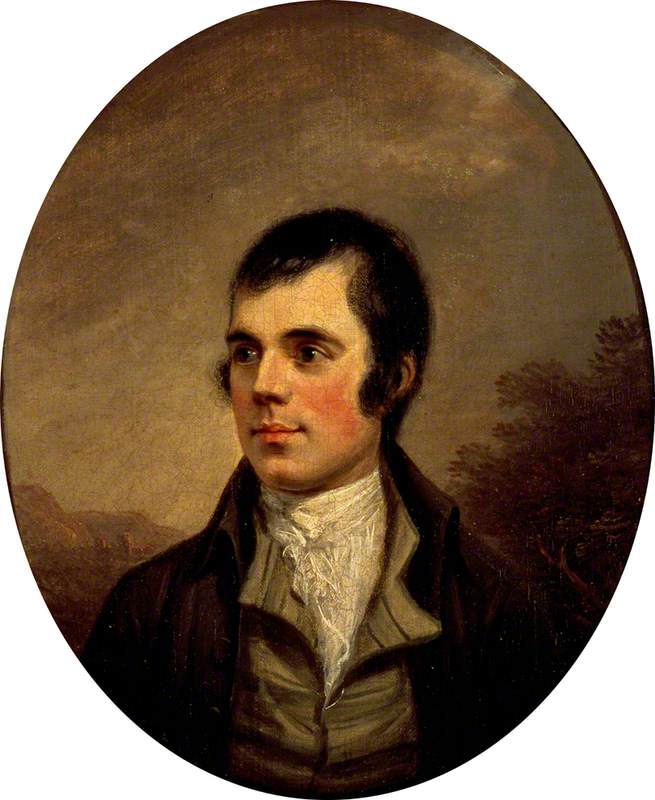

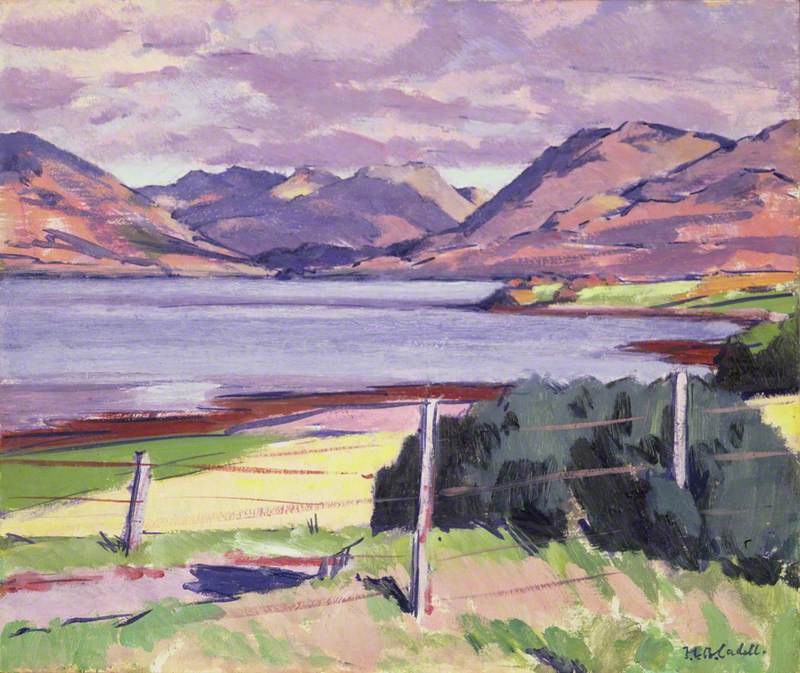

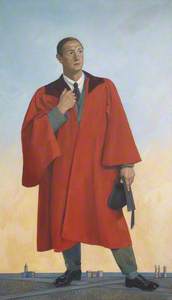

By the 1920s, Beatrice's own identity and path as an artist were clearly defined. Her marriage to the painter William Macdonald in 1925 created a unique artistic partnership and cemented her place within the Scottish art scene of the 1920s and 1930s, particularly in Edinburgh where Macdonald was already well established and a close friend of Scottish Colourists F. C. B. Cadell and Samuel Peploe. This is illustrated by surviving correspondence and in particular by a characterful portrait of a debonair William Macdonald by Cadell, dating from the mid-1920s.

Image credit: William Syson Foundation

William Macdonald

oil on canvas by Francis Campbell Boileau Cadell (1883–1937)

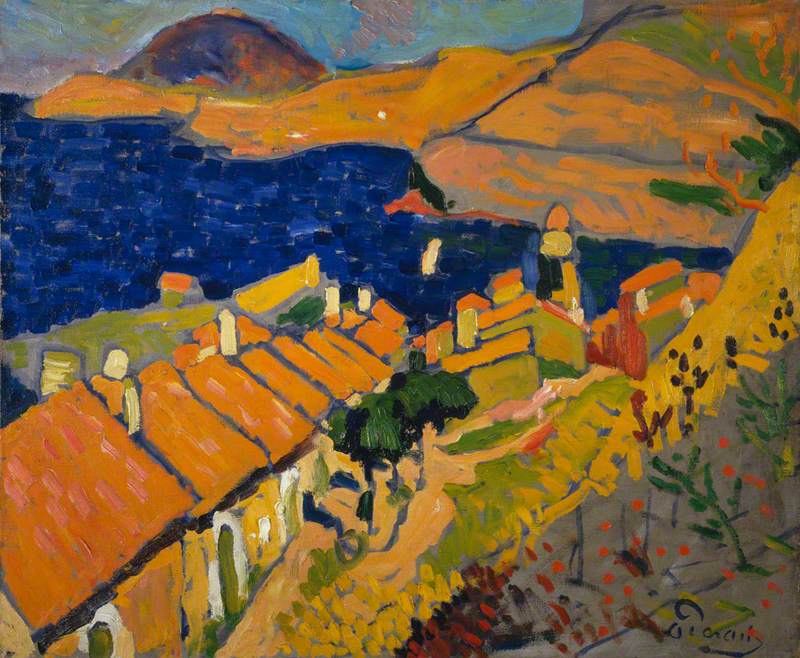

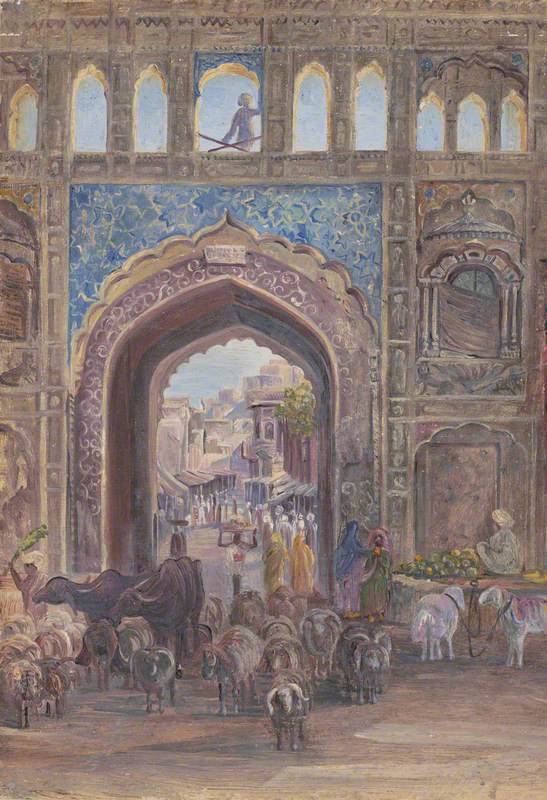

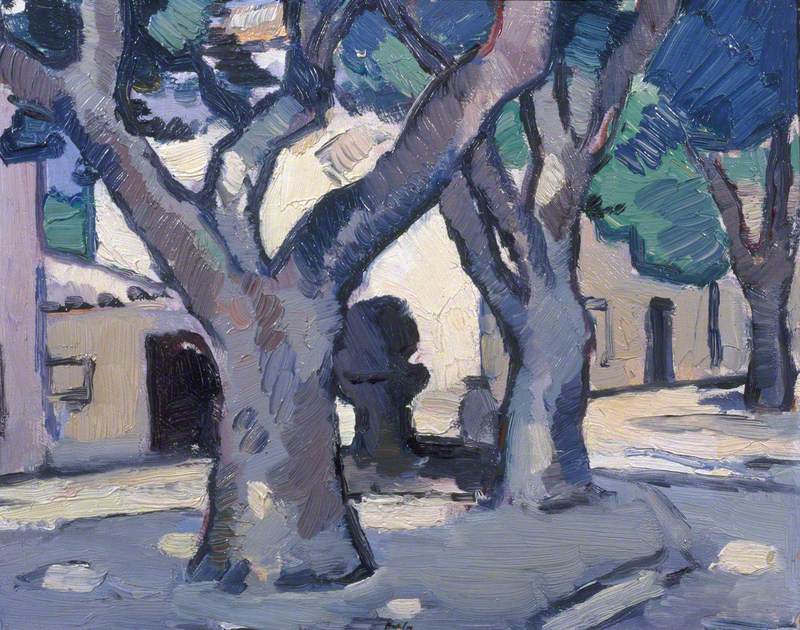

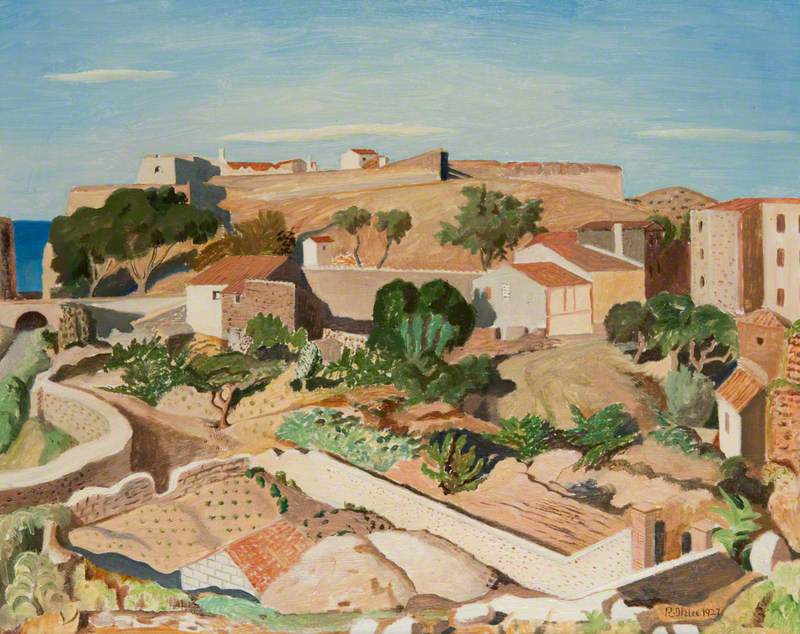

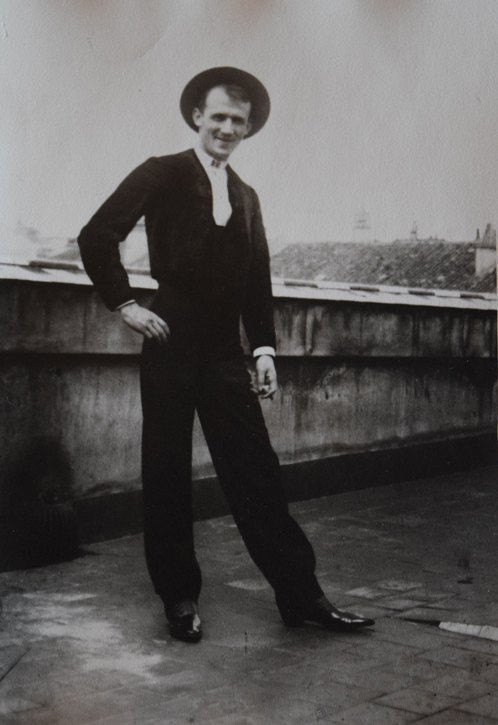

Macdonald's particular affinity for the arid landscapes of southern Spain had earned him the nickname William 'Spanish' Macdonald. Beatrice shared his love of travel and together they explored the Continent, returning frequently to the French Riviera and to southern Spain, taking as their base, for a time at least, the picturesque Mediterranean fishing village of Cassis in the South of France, a favoured haunt of the Colourists.

Image credit: William Syson Foundation

William Macdonald in Spanish dress

c.1920, unknown photographer

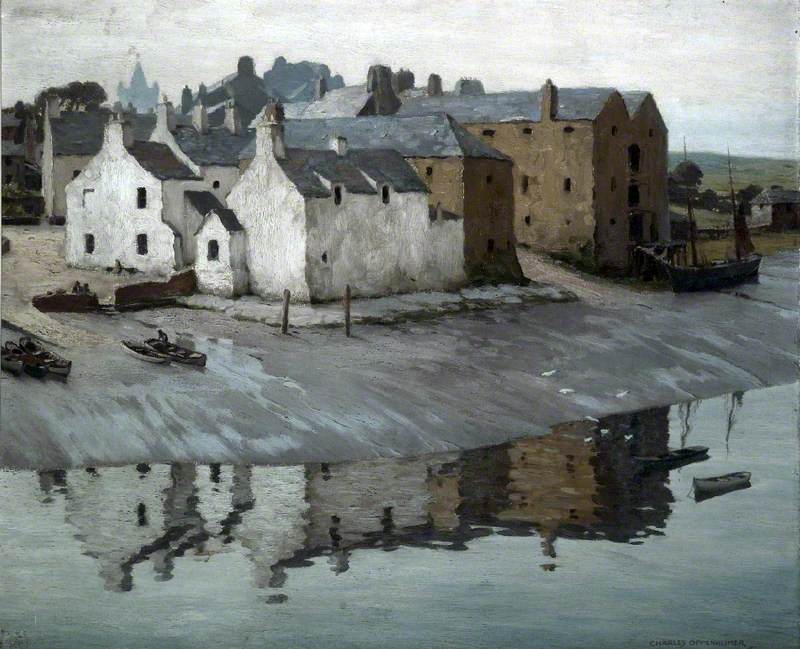

The couple moved in artistic milieux both at home and abroad, also spending time in Kirkcudbright in Galloway. Their time painting together in Spain culminated with a joint exhibition in 1928 at Messrs Watt and Sons, Dundee, entitled 'Pictures of Spain'.

Throughout her long career, Beatrice's style shows clear periods of evolution. Her early work is typified by the painting Nurse and Baby, with its soft, impressionistic brushwork and a carefully balanced composition.

In it, a delicate use of warm tones in an otherwise restricted palette somehow emphasises the vulnerability of the sitters, concentrating our attention upon the intense gaze of the nurse and just-seen head of the baby she cradles. Against the monochrome treatment of her uniform, the baby's blanket and the surrounding room, their humanity is thrown into relief.

Nurse and Baby was a painting with which Beatrice achieved some critical acclaim. It was selected for inclusion in the Royal Scottish Academy Annual Exhibition of 1939, although preparatory drawings in a portfolio of much earlier sketches would seem to date this painting to around 1915, when she was living and working independently in London. Certainly, it is consistent with the impressionistic style with which she approached a portrait of her mother that year, exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1916. Common to both portraits is the empathy with which she approaches her subjects.

© William Syson Foundation. Image credit: William Syson Foundation

My Mother

oil on canvas by Beatrice M. L. Huntington (1889–1988)

In 1948, nearly a decade after it was shown at the RSA, Beatrice submitted Nurse and Baby to the Royal Academy Annual Exhibition in London. With the founding of the NHS that year, its subject matter was certainly topical and it is not impossible that such a seismic event might have prompted her to revisit the painting.

Sometime after the First World War, Beatrice returned to Scotland, taking a studio near her family home in St Andrews. She became an active member of the Dundee Art Society and in 1920, joined the Society of Scottish Artists. Whether influenced by her experience in Paris and perhaps her continued connections there, or through her association with Macdonald, Beatrice's style shifted significantly in the early 1920s to show a clear Modernist influence and her most intense period of experimentation. Moving away from her impressionistic approach of the previous decade, she explored a starker stylisation and an austerity of design which was apparently informed by her understanding of Cubism.

A Muleteer from Andalucia (c.1923) and The Cellist (c.1924) exemplify her brief but successful engagement with Modernist art.

A Muleteer from Andalucia about 1923

Beatrice M. L. Huntington

Shown as Study of a Spaniard at the Society of Scottish Artists exhibition in Edinburgh in 1923, her Muleteer was described in The Times as being 'prominent among the figure work.' The sitter's pose is simplified to create a triangular silhouette: a degree of distortion which flattens the depth of field. The features are rendered with clearly defined blocks of colour and invested with a stark intensity.

The Cellist is another example of this treatment.

The slope of the sitter's shoulders is exaggerated, accentuating the angular, elongated neck, the impact heightened with the juxtaposition of orange against blue. But this work also provides a direct link with Beatrice's own experience. As an accomplished cellist herself, she went to Leipzig in 1924 to study for a short time under the tutelage of celebrated cellist Julius Klengel, performing in St Andrews on her return.

Another work close to home is her iconic painting of John Craig, known as The Student, 1927, now owned by the University of St Andrews.

Underpinned by her flair for design, it depicts the young Craig in the red gown of an undergraduate. He stands at the meeting point of two streets, arranged to form a Saltire or St Andrews cross: a topographical rendering of the townscape, whose prominent buildings – St Salvator's Chapel, the West Port and the ruins of the Cathedral – are silhouetted along a low horizon.

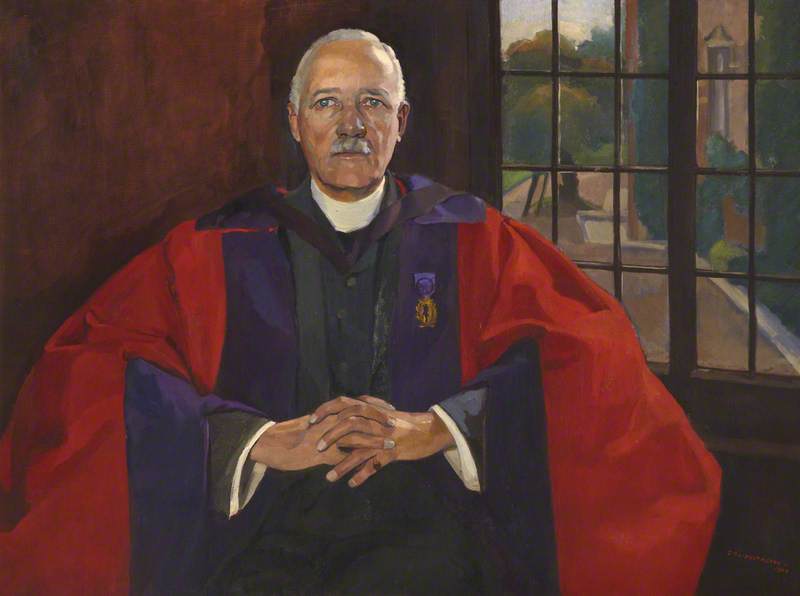

By the late 1920s Beatrice turned away from the suggestion of the avant-garde at which she hints in the Muleteer and The Cellist in favour of more traditional portraiture, evidently enjoying some commercial success, with commissions including Principal Galloway of St Mary's College, University of St Andrews.

The couple settled in Edinburgh in 1928, for the birth of their son Julius the following year. Although they continued to travel and were to spend much of the war living near Beatrice's sister in Canada, it was their gracious New Town flat in Edinburgh's Hanover Street that provided their permanent base. It remained Beatrice's home for the next sixty years and until recently housed a collection of paintings by both artists, alongside works by their friends and contemporaries.

Beatrice continued to exhibit widely into the 1950s and her work was well received. In 1931 the Society of Scottish Artists bought her painting Wilhelmina from their annual exhibition. The purchase was noted at the time in The Scotsman with the comment that 'it is still comparatively rare for a picture by a woman to gain special recognition.' In 1951 she was invited to join the Society of Scottish Women Artists.

William Macdonald suffered from ill health in his later years and Beatrice devoted herself to his care until his death in 1960. She returned to painting after a considerable break. Whilst her late style perhaps lacks the insightfulness or the strong design of her early work, it is characteristic of her unceasing appetite for reinvention that she returned to painting with a fresh approach. The features of the sitters are often strangely unfinished, the mouths and eyes unresolved as if the expression is so fleeting or changeable that it can't quite be pinned down.

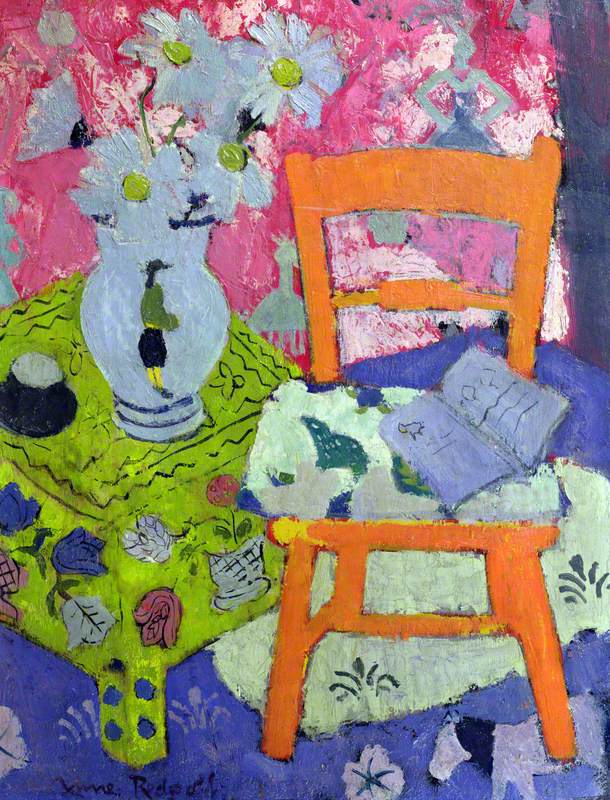

© William Syson Foundation. Image credit: William Syson Foundation

Violet Dreschfeld

oil on canvas by Beatrice M. L. Huntington (1889–1988)

A portrait of her lifelong friend, sculptor Violet Dreschfeld, as well as being an unflinching depiction of old age, gives the impression that to capture the expression would be to signify its end. This lack of resolution might therefore be an intentional avoidance of fixity; perhaps not a sign of failure but rather of optimism, as if at the end of her long life she reached the discovery that there must always be space for things to evolve.

Annabel Stansfeld, freelance writer