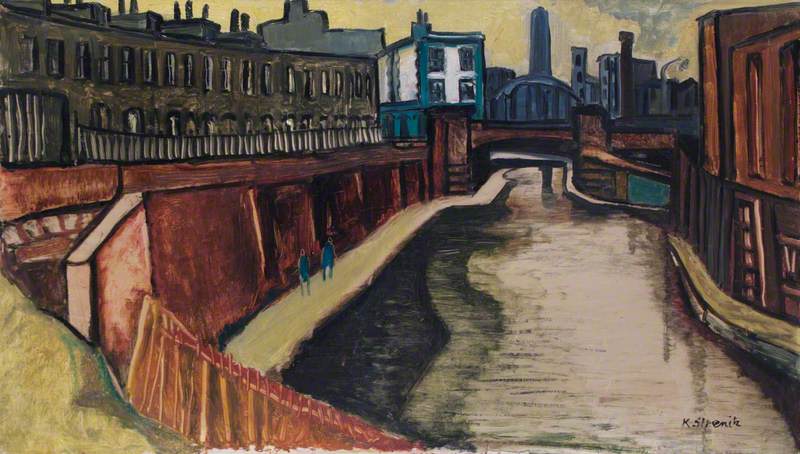

Nocturne, Grey and Silver: The Thames, Nocturne: Blue and Gold – Old Battersea Bridge... such evocative titles betray the moody atmosphere and pared-down aesthetic of Whistler's nocturnal images of the nineteenth-century city and have earned him lasting fame as an innovative, modernising artist.

As Whistler himself put it in his celebrated 'Ten O'Clock Lecture' (1885): 'The evening mist clothes the riverside with poetry, as with a veil, and the poor buildings lose themselves in the dim sky, and the tall chimneys become campanili, and the warehouses are palaces in the night, and the whole city hangs in the heavens, and fairy-land is before us.'

Nocturne: Blue and Gold - Old Battersea Bridge

c.1872–5

James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903)

What is, perhaps, less known is the well-spring for this vision – Whistler's deep-rooted family connections with early nineteenth-century industry and his early training as a young cadet officer at the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York.

Born in Lowell, Massachusetts, James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) came from a family of soldiers and engineers who were connected with many important technological projects of the day. Whistler's father, Major George Washington Whistler (1800–1849), a former topographical surveyor and engineer in the US military, met the Stephenson brothers during a trip to England in the 1820s, and later supervised the building of the St Petersburg to Moscow railway. Whistler's elder brother George William also worked as a railway engineer in America and Russia.

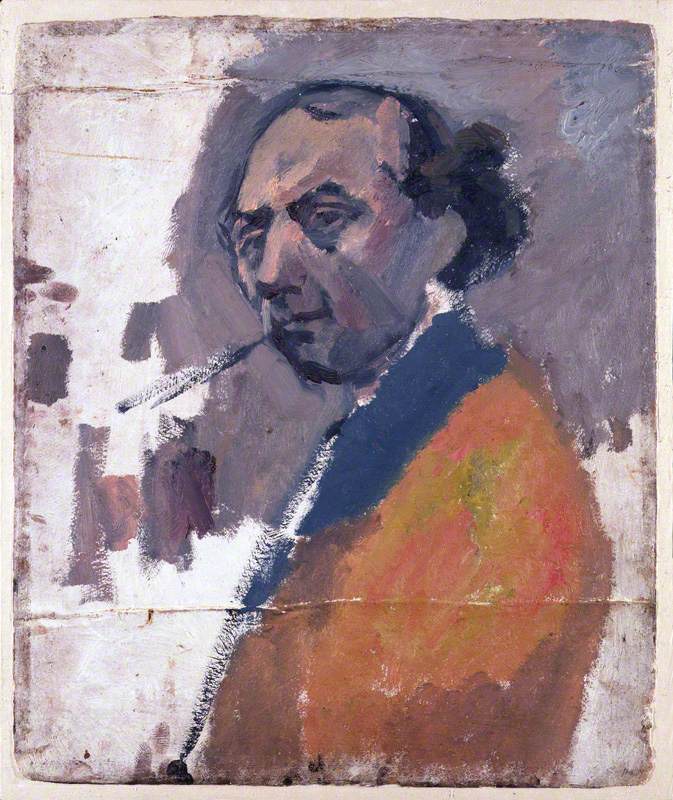

George Washington Whistler (1800–1849)

(father of James McNeill Whistler)

Chester Harding (1792–1866)

The family circle included innovators such as the Winans family, who ran a locomotive works in Baltimore, Maryland. In the late 1850s, the firm designed a revolutionary new ship, nicknamed the cigar boat, with a spindle-shaped hull driven by two steam engines. The artist's younger brother, Dr William Whistler, also made his scientific mark, becoming a leading throat specialist and a founder of the London Throat Hospital in 1887.

Drawing and map-making were important components of Whistler's military training at West Point where, from 1851 to 1854, he attempted to fulfil his father's wish that he should make engineering or architecture his profession. Later on, ejected for misdemeanours that included a deficiency in chemistry, he became an apprentice in the Drawing Department of the US Coast and Geodetic Survey, where he learnt to etch.

By 1855, however, aged 21, he had left for Paris to study art, fired up by the romantic bohemian characters portrayed by Henri Murger in his publication Scènes de la vie de bohème (1851) which was set in the Latin Quarter. During his time there, Whistler continued to benefit from his family's connections – Thomas de Kay Winans (1820–1878), whose sister Julia married Whistler's half-brother George, became his earliest patron, helping to finance his artistic studies.

James McNeill Whistler, Sketches on the Coast Survey Plate.https://t.co/BBpmevRB7n pic.twitter.com/sX3iwXWDzL

— NGA DC Art Bot (@ngadcartbot) November 28, 2020

In 1859, Whistler settled in London, the home of his half-sister Deborah and her husband Francis Seymour Haden, a prominent physician and amateur etcher who became another important early supporter of his work, encouraging him to work from nature and helping him to market his etchings.

La vielle aux loques (Old Woman Sorting Rags)

1858

James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903)

Influenced by Rembrandt, whose etched work he greatly admired, Whistler's early etched views of London and the Rhineland are notable for their focus on line and topographical accuracy. This can be seen in The 'Adam and Eve', Old Chelsea, a view made from Old Battersea Bridge near Whistler's home on Cheyne Walk (the pub was later demolished to make way for the Chelsea Embankment).

Yet also present is a desire for radical visual reinvention. An enthusiasm for Japanese block prints during the 1860s influenced Whistler's attitude to perspective and spatial relations between objects. This led him, in later nocturnes, to edit out details of the external world before him to its barest bones. His interest lay in its structural elements (in an echo of his family's engineering background) and in arriving at a balance of colour relations within the composition.

In his reimagining of the emergence of the first artist in history, Whistler pictured him as 'this designer of quaint patterns, this deviser of the beautiful who perceived in Nature about him curious curvings as faces are seen in the tire' ('Ten O'Clock Lecture').

Shibaura Seiran|江戸近郊八景之内 芝浦晴嵐|Clearing Weather at Shibaura by Utagawa Hiroshige https://t.co/gsOoSzLLg5 #utagawahiroshige #themet pic.twitter.com/WYVSuRMH5P

— The Met: Asian Art (@met_asianart) September 24, 2017

In a reflection in his 'Ten O'Clock Lecture' of his reported attitude towards J. M. W. Turner and Claude Lorrain, Whistler wrote: 'how dutifully the casual in Nature is accepted as sublime, may be gathered from the unlimited admiration daily produced by a very foolish sunset'.

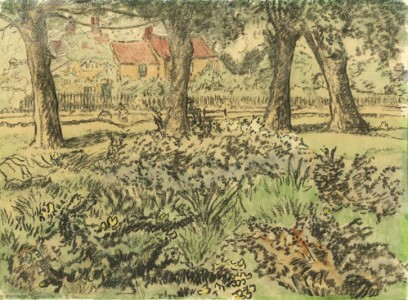

Despite his self-proclaimed ambivalence towards nature, close observation of nature and its moods underpins his reductive vision of nineteenth-century life. His images seek out gradations between the natural and human-made worlds – rivers and wharves, gardens and courtyards, between the naturalistic and the productive landscape.

They portray the timeless effects of weather and pollution, of sparks and smoke shooting across the night sky, as in his Nocturne: Black and Gold – The Fire Wheel, an image of a pyrotechnic display at the Cremorne pleasure gardens, a short walk from his home.

His vision is underpinned by family kinships that included makers of railroads, bridges and ships, cornerstones of Victorian urban life and trade.

Green and Silver: The Great Sea

1899

James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903)

At the same time, Whistler's colourful public personality as dandy, wit and pugilist (sparring partners included Oscar Wilde and John Ruskin) often overshadows the behind-the-scenes industry that took place in his studio. He often worked on paintings over a series of years, revising the composition many times or even obliterating the original entirely.

Similarly, in his etching practice, he would develop the composition over different states, employing different techniques to achieve varying textures and effects. For example, during printings of his Venice etchings, Whistler often left a thin coating of ink on the surface of the copper plate to create suggestive visual and compositional effects, in a process known as plate tone.

James Abbot McNeill Whistler, Nocturne: Palaces, 1879-1880 https://t.co/QQUmB7dxdu #printsanddrawings #minneapolisinstituteofart pic.twitter.com/ncNwSSMS3x

— MIA: Prints and Drawings (Bot) (@mia_drawings) April 28, 2021

Whistler's early reputation as an artist was earned through his etched work, leading him to employ marketing practices then considered innovative. For example, he assembled four groups of etchings and drypoints (the latter technique a close relative) which he marketed as published sets that became known as the 'French Set', 'Thames Set', 'First Venice Set' and 'Second Venice Set'. These sets were usually mounted and sometimes sold in albums.

Whistler also worked on several groups of related prints that were not, in the end, published, including the 'Brussels Set', 'Jubilee Set' and 'Amsterdam Set'.

During the 1880s and 1890s, Whistler executed a series of charming small oil panels on coastal subjects that he had framed in deeply recessed, reeded frames of his own trademark design and which draw the eye of the viewer towards the subject. The product of his many sketching trips along the coasts of England, France and the Netherlands, these works include Green and Silver: The Great Sea, painted at the seaside resort of Pourville-sur-Mer, near Dieppe during the early autumn of 1899, in which Whistler portrays the light and colour effects of the stormy green-grey sea breaking over the beach.

He wrote to an artist friend at the time: 'September & October are clearly the months for the sea – I am just beginning to understand the principle of these things – You know how I always reduce things to principles!'

This sense of always looking forward and of building upon past traditions is a core element of our current exhibition, 'Whistler: Art and Legacy' at The Hunterian, University of Glasgow (9th July to 31st October 2021), which explores the story of Whistler's art, while also telling the story of a collection and its legacy to the present day.

Patricia de Montfort, University of Glasgow