Visual artist Anthony Schrag undertook a residency with Culture Perth and Kinross, working alongside collection staff. Here he writes for Art UK about the resulting exhibition at Perth Museum & Art Gallery, and the meaning of a public collection.

As an artist, the central focus of my work examines the role of art in participatory and public contexts. But while my practice stems come from a legacy of socially-engaged art – which would traditionally be focused towards 'the public' – my work usually begins inside cultural organisations.

I am keen to explore how infrastructures of management impact and affect cultural participation, and so need to understand the embedded power dynamics within an institution before I begin engaging with a 'community'.

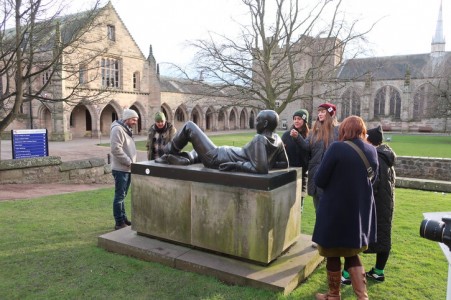

Anthony Schrag during his residency with Culture Perth and Kinross

The 'Kill Your Darlings' project is the culmination of a residency I undertook with Culture Perth and Kinross (CPK). CPK is the cultural trust that manages the Perth Museum & Art Gallery collection on behalf of the local authority – many of the paintings and sculptures can be explored on Art UK – and I undertook many months of working inside their offices, museum stores and alongside their staff.

This residency helped to frame the 'Kill Your Darlings' exhibition, but before I discuss this project, it is important to provide some context on some of the main themes in my work.

Anthony Schrag during his residency with Culture Perth and Kinross

The philosopher Emmanuel Levinas suggested that as social creatures, humans can only ever understand ourselves when we encounter 'the other' – something that is different from us. Indeed, he suggests that the more we are able to witness and experience something 'not us', the more we are able to learn about ourselves and the surrounding world. In other words, we understand ourselves in opposition, in the same way that light can only be understood through darkness; or joy only truly comprehended because of sadness.

It is difference that provides contrast, and in that contrast we see our edges more clearly. Levinas goes on to say that this engagement with something 'other' can be very difficult because it exposes us to the essentially socially plural nature of human culture: it shows that the world is made up of multiple, different – sometimes opposing – systems of value and otherness. So how do these notions of 'otherness' (and its associated difficulty) play out in a public collection such as the Perth Museum – or even on the Art UK website – and how can organisations navigate all the multiple values within a social sphere? This notion of 'multiple values' in a public domain became the central thrust of the 'Kill Your Darlings' project.

Art UK features many of the culturally diverse items that are held in the Perth and Kinross collection, including religious iconography such as Saint Bartholomew; poetic and allegorical imagery such as The Battle of the Amazons; or 'world culture' (to use a problematic term) items such as the Ngãti Porou House Panel. Just these three examples already unpick potential differences in politics, passions and preferences that might not sit comfortably together.

On one hand, you could suggest that a public art collection should be one in which everything is gathered, but this belies the reality that important stories are missing. Where are works by women? Where are the stories of people of colour? Where are the ephemeral and intangible cultural offers that do not easily fit into the classical 'art' paradigm?

As such, we have to make the conclusion that these public collections are a collection of some publics, which raises the question – how can we encounter other publics? And what does it mean to engage with such 'otherness' that is 'not us'?

Originally, my idea for the 'Kill Your Darlings' project was a provocation that we open the collection to the public and invite them to choose a single item that should be destroyed. How this single item would be chosen was up for negotiation, and how this item might be destroyed was similarly up for discussion, but I felt this provocation could begin to reflect the nuanced complexities of how – and if – an entire public could be represented by a museum collection.

When I proposed this project, one member of the collections staff at CPK turned to me and jokingly said: 'You're not getting your hands on any of my collection.' We laughed, but the comment stuck with me: the proposition was not about me getting my hands on the collection. Rather, I was looking for a way to allow the public to reflect on the collection and in doing so bring to the fore different opinions, values and insights.

Installation view of 'Kill Your Darlings' at Perth Museum & Art Gallery

Additionally, I reflected that the comment alluded to an interesting conundrum – the collection managers are experts, but also gatekeepers. The collection belongs to the citizens of Perth and Kinross, not any specific organisation.

The collection staff – who work in an underfunded, and often stressful, sector – obviously fully understand this distinction. But I think the comment does raise some questions: How do the people of Perth and Kinross have ownership of the collection? How do they understand it? What do they think of the collection? Indeed, how does this work in regards to all the works on Art UK? One might suggest that such accessibility of records online means that they are more public than those kept behind locked doors in temperature-controlled, protected environments. But is this true?

While COVID-19 has highlighted issues such as digital poverty, it has also highlighted the class-orientation of traditionally funded cultural activity: sure, anyone can access Art UK – or the Perth Museum stores – but do they?

There are many traditional barriers to accessing art, some of which are removed by digital access provided by Art UK, seen in the millions of users of the site each year, whereas others are more difficult to pinpoint.

As a provocation, consider that many works on the site are by middle-class, dead, white men – for example, J. D. Fergusson. If the collection mainly speaks of their history, how – and why – would someone who was outside of these groups engage with the collection? Where would they even start?

This underpins the central paradox of museum collections: what should a collection do? Can a collection ever speak to everyone? And if not, who is being excluded? Why are those voices silenced? What if those silenced voices have different values from those charged with protecting and caring for the collection? Is that OK? Or, does the idea of the general public having a direct say on what happens with priceless objects make us feel uncomfortable?

If those excluded voices have a say, does this problematise our supposed expertise? Our training? Our jobs? And yet, surely the role of a public collection is to be for the public? Fundamentally, how is the plurality of social values understood in the context of any collection? I have no answers for this, but I do think that there is space to reflect on how that collection speaks for, with, at or alongside the public, and want to encourage a deeper conversation with the 'true owners' of the collection, as well as those experts who care deeply for it.

Installation view of 'Kill Your Darlings' at Perth Museum & Art Gallery

Understandably, CPK felt my provocation for destruction too difficult. They were concerned that the public would see this as a tacit agreement of destruction, rather than an invitation to participate in democratic processes.

Although I was clear that I was not actually proposing to destroy anything and instead the piece was an exercise in what author Lewis Hyde would call 'disruptive imagination', it was felt by the organisation that such nuance could be lost, and the organisation would be exposed to a stormy onslaught of public opinion that would be difficult to weather.

I am also aware that cultural organisations lead precarious lives at best, and that such storms can potentially lead to a loss of funding. I understand this and so agreed to adapt the project to a 'safer' option. But I am also disappointed because I believe art is supposed to be risky. It is supposed to ask difficult questions. It is supposed to expose us to 'the other'.

Installation view of 'Kill Your Darlings', including 'Neoclassical Figure of an Unknown Woman'

As such, through fruitful conversations and extensive support from the collection managers, the project has resulted in the 'Kill Your Darlings' exhibition. This exhibition, I believe, touches on these important ideas of value, publicness, and dissensus. I have also commissioned a series of conversations to explore this in more discursive frameworks.

The final work consists of an exhibition that features three elements. The first is a pile of representative items from the collection: taxidermy fish sit next to marble statues, rare cameras from the 1800s lean against archaeological finds and bones; Roman coins sit next to sporrans from the seventeenth century; oil paintings and insects brush up against scientific instruments. Some of these can be found on Art UK (for example, Neoclassical Figure of an Unknown Woman).

As the Senior Collection Manager said, despairingly, this display gives the impression of being 'more junk shop than museum'. But isn't a museum a junk shop of a different name? Just a collection of old stuff valued by some, but not by others? This part of the exhibition, therefore, aims to challenge what a collection should be.

The second part of the exhibition features a public vote where people are asked to choose which of 11 objects is the 'most valuable'. That notion of 'value' is undefined, and left for the public to interpret. Importantly, the votes are visible to other participants, so everyone can see how items are being valued by others – this may or may not influence their choices.

At the time of publication, a pair of Inuit snow goggles were considered the most valued, over other objects including local artisan glass, engraved pistols, marble sculptures, taxidermy, precious jewels and world cultures. The item with the least number of votes will be symbolically destroyed at the close of the exhibition.

These fab Inuit snow goggles have currently received the most votes as the 'most valued' object in @anthonyschrag's exhibition, Kill Your Darlings. Made from wood and leather, they have been shaped to fit closely the face with small slits barely big enough to see through. pic.twitter.com/URbGifSbXK

— Culture Perth & Kinross Museums (@CPKMuseums) March 14, 2022

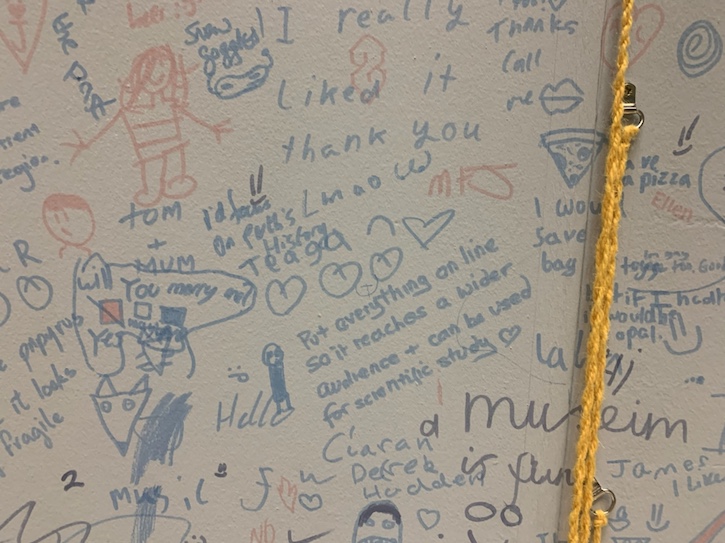

The last element invites the public to write directly onto the walls of the museum, allowing their opinions and considerations to sit in direct conversation with others. Often, these are oppositional perspectives, but they highlight and underpin the diversity of public insight and opinion.

Writing on the museum wall by visitors to the 'Kill Your Darlings' exhibition

This diversity of value brings us back to notions of 'otherness' and public engagement: how might any collection encourage such public conversation? Consider Fergusson's Self-Portrait: The Grey Hat – how can this item speak to multiple publics? Do we have enough of this type of story, and if we removed it from the public domain, would we be lesser? Or would we be making space for other stories? How can we confront ourselves and present new formats of a public museum collection? My suggestion is that the answer lies in a potential denial: let's imagine it gone, finished and destroyed ... and let's work backwards from that to ensure we get it right.

Anthony Schrag, artist, researcher and senior lecturer

'Kill Your Darlings' is open at Perth Museum & Art Gallery until 8th May 2022

This content was supported by Creative Scotland