Pallant House Gallery in Chichester houses one of the finest collections of modern art in Britain. A few years ago the gallery held a small show of my own work, and so I was lucky enough to return to the gallery recurrently over a short space of time. During the course of these visits I explored its extensive collection, and found myself repeatedly drawn to a painting by Michael Andrews.

Thames Painting: The Estuary (Mouth of the Thames)

1994–1995

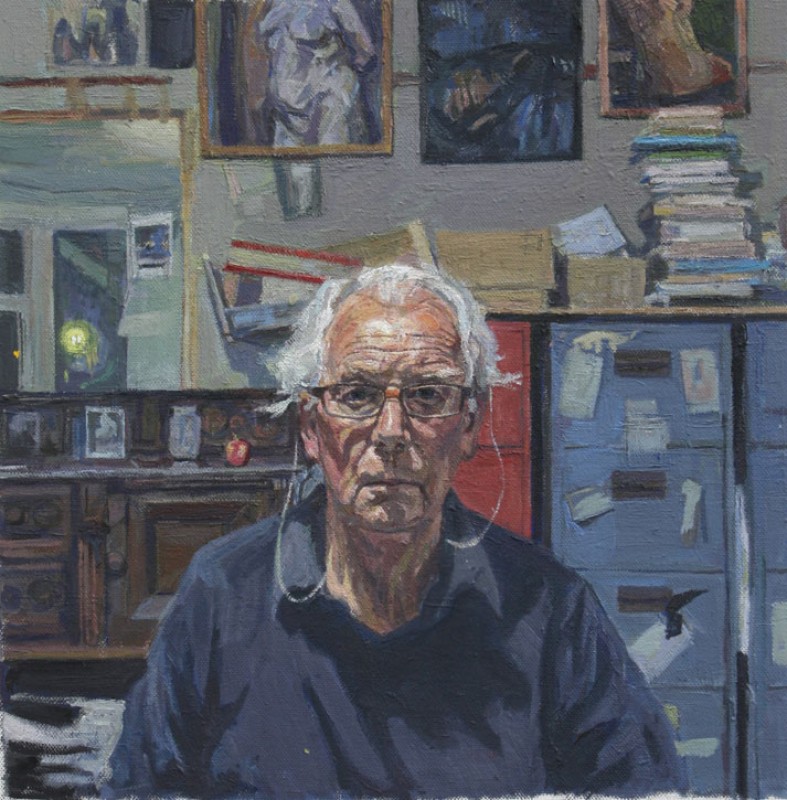

Michael Andrews (1928–1995)

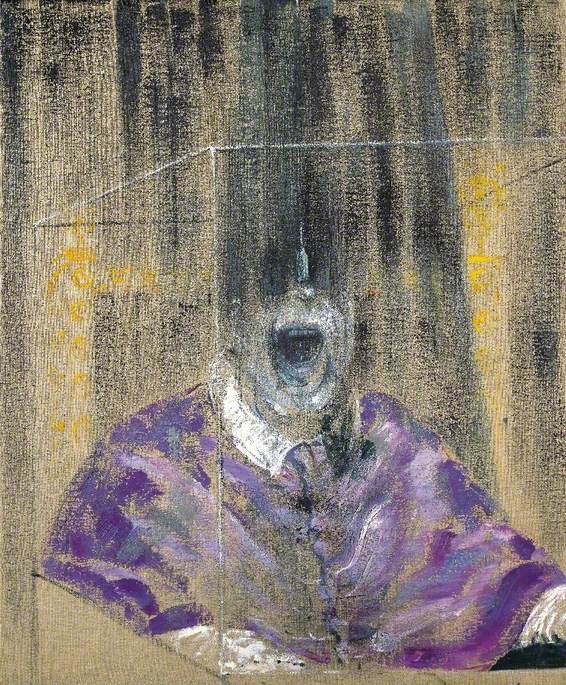

His enigmatic Thames Painting: The Estuary (Mouth of the Thames) (1994–1995) normally hangs opposite a work by his ‘London School’ contemporary Francis Bacon. This positioning highlights its quiet strength. It lacks the ability of a Bacon to instantly tap into your nervous system; no screams pouring out of anuses or spine blades slicing open squirming cadavers. In place of Bacon’s white noise and theatre of horror is something silent and unassuming. But given time and contemplation Michael Andrews’ Thames work is one of the most seductive and powerful paintings I have ever encountered.

Andrews’ subject matter is somewhat unremarkable: a sloping view down upon the Thames Estuary, complete with jetty, onlookers and a few fishermen. The effect of the angle of viewing is to flatten the picture plane. Only the presence of a few diagonals and the scaling of the figures give us any sense of perspective. It is a picture that teeters on a brink, shifting between an awareness of flatness and the suggestion of depth.

Its power resides in the manipulation of materials in Andrews’ process. He must have laid his canvas flat to his studio floor, before pouring, pooling and spreading a range of oil-based materials across its surface in a series of layers. Puddles of thinned oil paint have shifted across the plain. The wash of them has in turn been broken up by the corrosive nature of turpentine, leaving traces of their history like deposits at the bottom of a river. These are organic materials that present us with memories of their journeys. Clumping splashes of varnish appear to float on top and across the surface; as if in a state of constant flux. Andrews acts as a conductor of sorts – his orchestra of effects speaks eloquently, and without contradiction, about their own painterly identity and the nature of their subject.

The painting depicts distant figures on the border between land and water. This seemingly humble subject matter hints at something far more profound, as revealed by the mechanics of the picture’s material make-up. This is a painting that explores liminality. Everything about it situates us on the threshold between opposing states. It transcends the literal limits of its subject matter to offer up a metaphysical experience akin to Turner at his best. It holds the Romantic notion of the sublime at its quiet core, offers up an existential view of humanity’s insignificance in the face of nature. Yet it is not explored through the bombast of a storm, but instead through visual rhythms akin to the slow ebb of an estuary.

That it should be one of the last paintings Andrews made before his death from cancer seems poetic and poignant. Such biographical projections are normally pointless, but when stood in front of a work that so eloquently expresses the fragility and transience of life, it is hard not to be moved to make such connections. It is a mournful, poetic lament in the mould of T. S Elliot’s masterpiece, The love song of J. Alfred Prufrock – as William Feaver said, ‘An elegy to dissolution’.

Tom de Freston, Contemporary History Painter