William Morris (1834–1896) is likely the first artist to come to mind when thinking about the Arts and Crafts movement in Britain. Morris was a textile designer, artist, printmaker, writer and socialist reformer born in the nineteenth century. His designs have continued to stay popular up to the present day – there are several museums related to William Morris in the UK alone.

But at the height of his popularity, in around 1870, there was actually another Arts and Crafts artist working in a wide array of mediums, who – just like Morris – was involved with members of the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood and influenced by John Ruskin.

Phoebe Anna Traquair – who, by 1920, would be elected an honorary member of the Royal Scottish Academy – was an embroiderer, bookbinder, enamellist, jewellery designer, mural painter and manuscript-illuminator. Despite her wide-ranging talents, Traquair is the great Arts and Crafts artist you've most likely never heard of.

The artist was born Phoebe Anna Moss in Ireland in 1852. While still a student at the School of Design of the Royal Dublin Society, she took up work illustrating fossil fish specimens for Ramsay Heatley Traquair, a young palaeontologist. The pair married in 1873. A year later, Ramsay was appointed Keeper of Natural History at the Museum of Science in Scotland and the couple moved from Dublin to Edinburgh.

Initially, Traquair's artistic work was delayed by her domestic duties – she had three children with Ramsay and it wasn't until the 1880s that she began in earnest to work as an artist.

Hilda Traquair, Age Five Years

(portrait miniature) 1884

Phoebe Anna Traquair

This 1884 watercolour is a portrait of Traquair's daughter Hilda. During this period, Traquair mainly focused on the design of practical embroideries and casual landscape paintings made on family holidays. A sensitive image of childhood, it demonstrates Traquair's early artistic abilities.

In the same year, Traquair received her first professional commission.

The Royal Hospital for Sick Children in Edinburgh elected to add a mortuary chapel to their site – turning a disused coal house into a room to hold respectfully hold bodies for the parents before burials. It was decided that the small chapel should feature murals that offered comfort to grieving parents and the young artist and mother Phoebe Anna Traquair was approached to paint them.

The design Traquair planned focused on themes of motherhood and the journey of the spirit through life and beyond. Her ambitious scheme combined features of the Celtic revival with medieval imagery similar to manuscript illumination: the practice of decorating a text document with illustrations, patterns and design.

The mortuary chapel of the Royal Hospital for Sick Children in Sciennes, Edinburgh

1884, mural paintings by Phoebe Anna Traquair (1852–1936)

The influence of manuscript illumination on the project was no coincidence – while working on the murals at the Royal Hospital, Traquair was also developing her other art forms, including manuscript illumination.

Typically seen in medieval manuscripts, Traquair took up the art form after being inspired by her friend John Miller Gray, the first curator of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. Gray enjoyed the poetry of Pre-Raphaelite artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti and encouraged Traquair to produce modern manuscripts of his work.

In 1886, Traquair wrote to John Ruskin – the writer and great supporter of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood – for advice on the art of illumination. Throughout 1887 Ruskin sent Traquair a number of medieval manuscripts from France and Italy to help her work in exchange for a look at her own illuminations.

Illumination, Featuring a Hare

late 19th C–early 20th C

Phoebe Anna Traquair

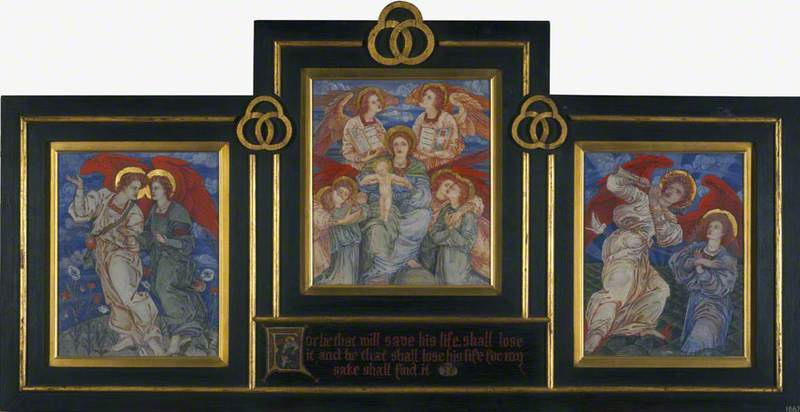

Often religious in nature, manuscript illumination suited Traquair not only through her intense curiosity in terms of craft, but also because of her Christian faith, which underscored much of her work. As she wrote to her nephew in 1908: 'There is only one real thing in this world and that is religion.'

Her focus on religion could be found across all the art forms she worked in. Alongside murals, illuminations and paintings, Traquair was also a skilled embroiderer. Unlike Morris, whose embroidery designs were stitched by others (often his wife and daughter), Traquair designed and sewed each of her works herself.

Far from 'twee' embroideries, Traquair's needlework was as ambitious in design and scale as her vast murals.

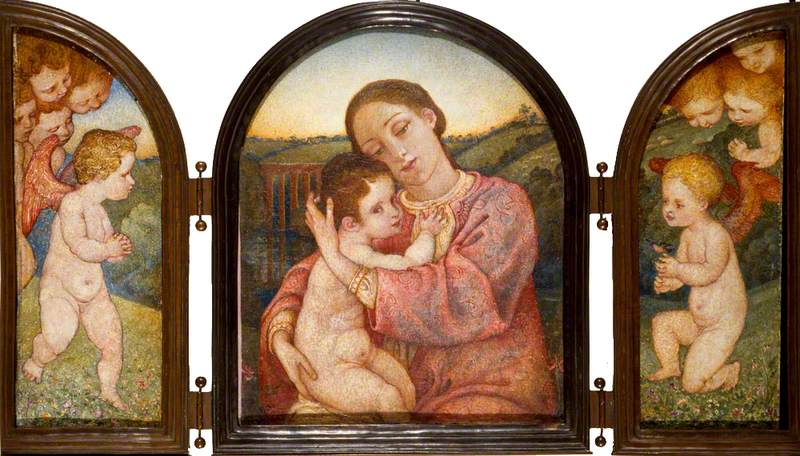

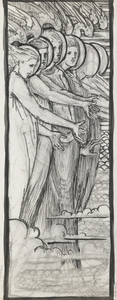

Study for the Souls of the Blest

c.1890

Phoebe Anna Traquair

This rare surviving design is for an embroidered panel in a draught screen. It shows a collection of six angels receiving the souls of the just from the Angel of Redemption. The panel was one of three, and together they show the journey of the soul – a theme often found throughout Traquair's work.

The final piece was called The Salvation of Mankind and combined different kinds of complex embroidery stitches including couching, running stitch and goldwork.

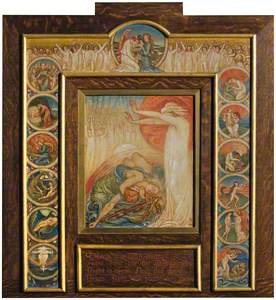

The Salvation of Mankind

(detail), 1886–1893, embroidery by Phoebe Anna Traquair (1852–1936)

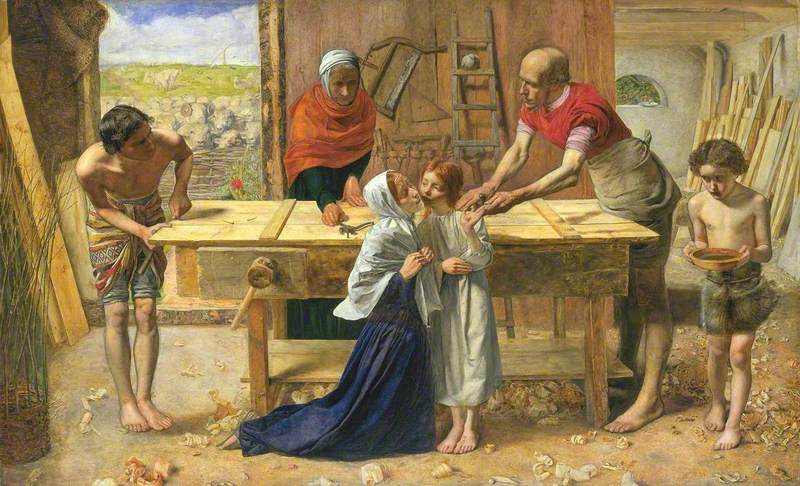

Moving into the late 1880s and early 1890s, Traquair's style changed from a more figurative Pre-Raphaelite approach to a Renaissance naturalism, inspired in part by her trips to Italy where she saw the work of Sandro Botticelli, among others.

You can recognise Botticelli's influence in the 1807 painting Cupid's Darts. The female figures here have similar physicalities and structured curls to many of Botticelli's most famous works – including those shown in Primavera, which Traquair also used as the basis for a painted panel at Kellie Castle in Fife.

Primavera

1482, tempera on wood by Sandro Botticelli (1444/1445–1510)

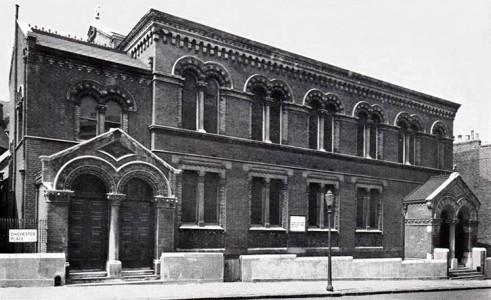

This time period also saw her take on her most ambitious project to date at the Catholic Apostolic Church.

The story is that Traquair walked into the church during service one day and simply declared that she would like to paint the walls. The result was a set of stunning murals, often referred to as Edinburgh's Sistine Chapel. Her design featured individual portraits of every single member of the church's congregation and depictions of religious parables combined with Traquair's own philosophies.

Traquair's scheme is uplifting: the murals are a vast celebration influenced by the bright, incense-filled aesthetic of the church itself.

Catholic Apostolic Church, Edinburgh

1890s, murals by Phoebe Anna Traquair (1852–1936)

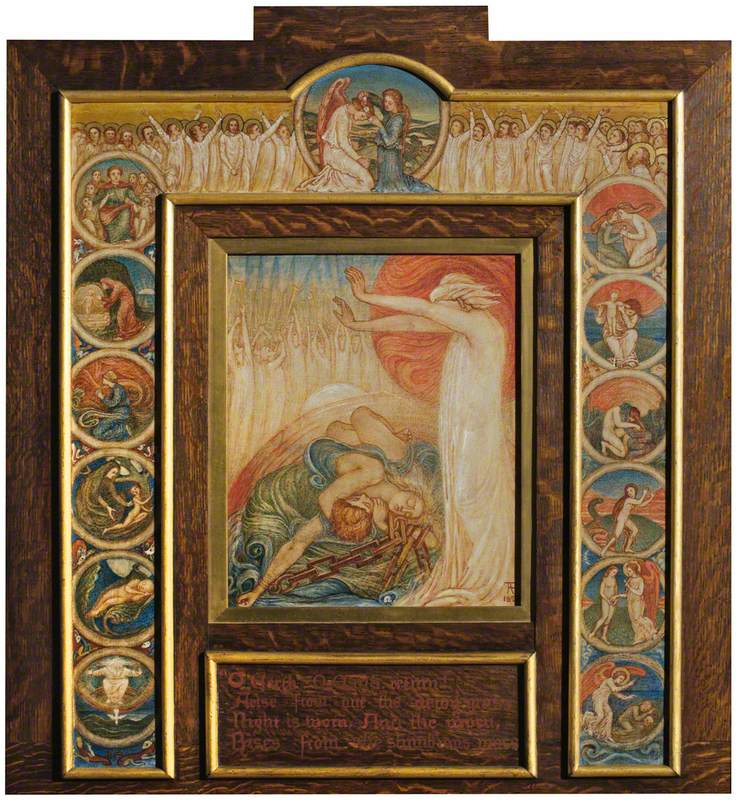

While Traquair was painting this project, she was also working on another ambitious embroidery: four panels called The Progress of a Soul – a scheme that combines Walter Pater's story of Denys l'Auxerrois (a version of the Greek myth of Dionysus) with the Christian journey of trials, redemption and resurrection.

The Progress of a Soul: The Entrance

1895, silk & gold thread embroidered on linen by Phoebe Anna Traquair (1852–1936)

As reported in The International Studio in 1905, Traquair worked on the embroideries in 'a given spare hour of each day' while completing the work at the Catholic Apostolic Church – hand stitching each of the six-foot panels.

Traquair finished the embroideries in 1905 at the age of 53. In her later years, she took up even more art forms, becoming interested in enamelling and jewellery design. While Traquair's application for professional membership of the Royal Scottish Academy was initially rejected, in 1920 she was elected an honorary member. However, she began to lose her sight and stopped producing work beyond 1925.

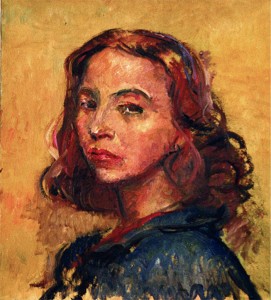

Her last self-portrait, painted in 1911, shows the artist at 59 years old, staring confidently out from the canvas. From her early beginnings, illustrating scientific specimens for her husband, Traquair had grown into an accomplished artist and is now considered, by National Museums Scotland, to be 'the first important professional woman artist of modern Scotland.'

Phoebe Anna Traquair (1852–1936), Artist, Self Portrait

1911

Phoebe Anna Traquair (1852–1936)

The painting was bequeathed to the National Galleries of Scotland by Traquair's son who called it 'the best portrait of her ever done.'

After her death in 1936, Traquair's work fell rapidly out of favour and her legacy remained mostly neglected right up until the early 1990s.

Today you can find her self-portrait at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery and, if you time your visit to coincide with the last Sunday of the month, you can also take a tour of the Catholic Apostolic Church (now the Mansfield Traquair Centre) and marvel at the incredible work of one of the greatest Arts and Crafts artists of all time.

Molly Skinner, writer, producer and art historian

Further reading

Elizabeth S. Cumming, 'Phoebe Anna Traquair HRSA (1852–1936) and her Contribution to Arts and Crafts in Edinburgh', University of Edinburgh, 1986

Great Scottish Art, 'Catholic Apostolic Church – Phoebe Anna Traquair', 2015