Photographing sculptors for more than 30 years has made me look differently at sculptures and monuments that we see in public spaces. I have developed a habit of searching for the small plates with artists’ names on sculptures and looking up information about them. It reveals much about the stories behind the work.

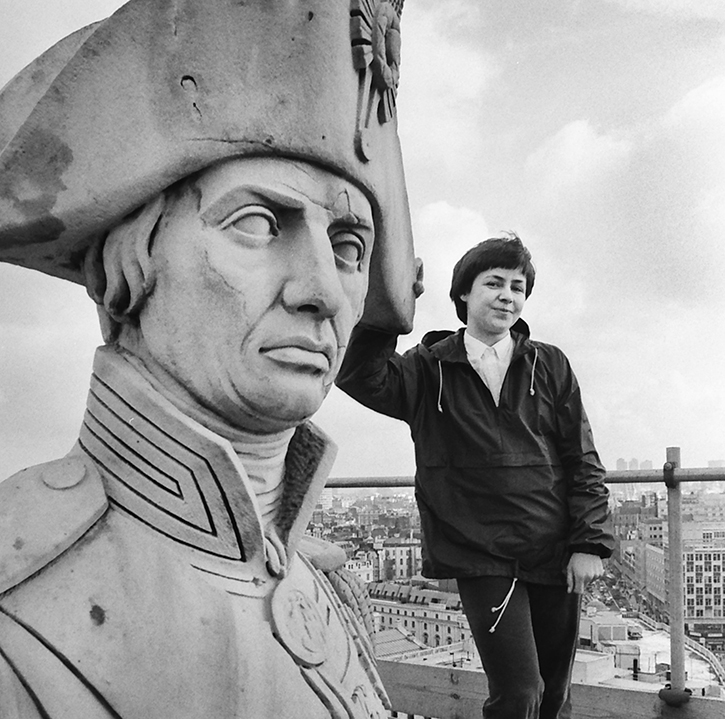

Anne Purkiss at the top of Nelson's Column, 1987

Passers-by who take selfies from the sundial sculpture at London’s St Catherine’s Dock against the backdrop of Tower Bridge would hardly know that the artist who made it works in a studio in an old pump house just a few hundred yards away, or that the same artist has arguably created more public sculptures in London than any other contemporary sculptor, and that this artist is a woman – Wendy Taylor.

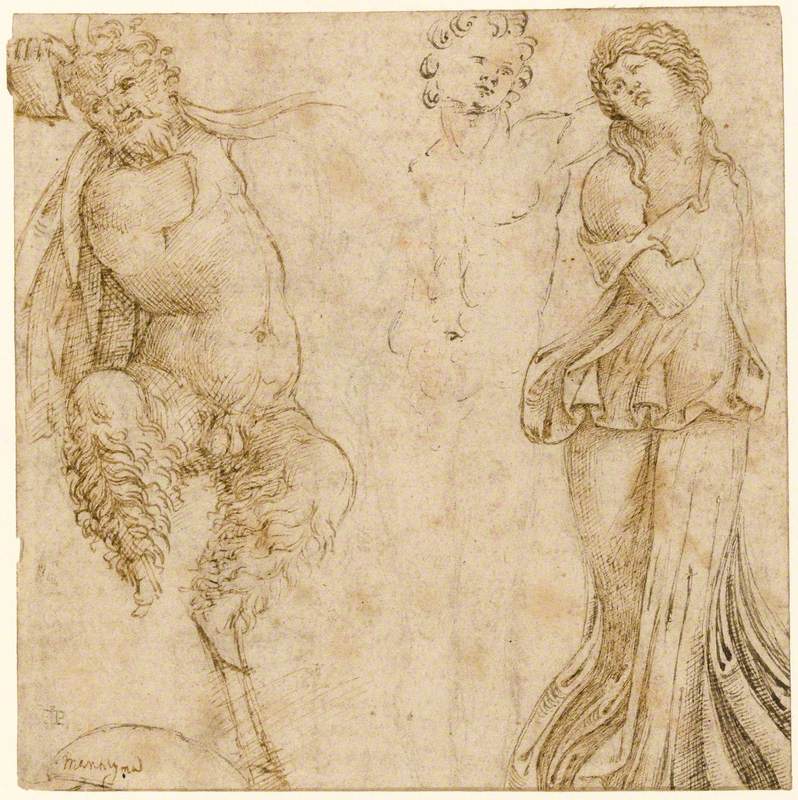

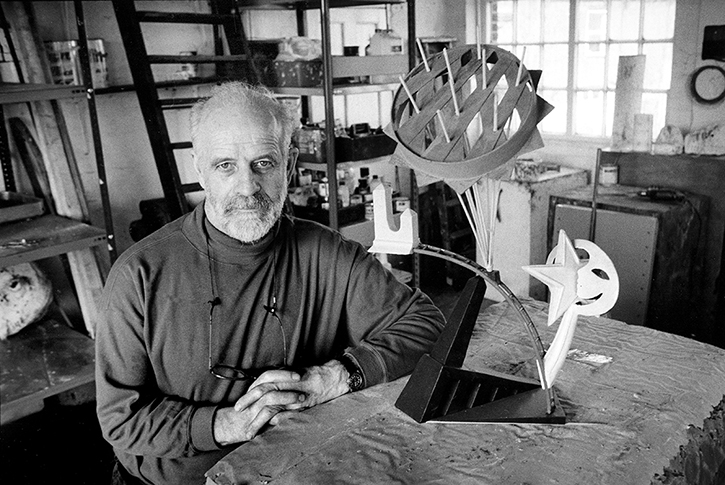

The work of Geoffrey Clarke is always associated with the rebuilding of Coventry Cathedral, with his ‘Cross of Nails’ and some of the glass windows. I visited him years later at his home in Suffolk and met an entire family of artists. Jonathan Clarke, his son, is also an award-winning sculptor. Geoffrey's wife Ethelwynne was, like many women of her generation, too modest to seek publicity for herself and her work, but the photograph I took of father and son in 1994 remains the only picture of both sculptors together in their studio.

Cornelia Parker, London, 2013

Several of the earlier sculptors’ portraits were commissioned by the COI Overseas Press Service. The task was not always as easy as it may appear. Sir Anthony Caro had agreed to photographs of him in his studio. When I got there, it turned out that he was unexpectedly busy, telling me: ‘You can take any pictures you like, but I haven’t got time to pose for photos’. Barry Flanagan, known for his sculptures of leaping hares, suggested that we I should take a photograph of him at the East London foundry that cast his work. When we got there, he suddenly changed his mind and said that he didn’t want to do this after all. The picture tells nothing of a very tense moment.

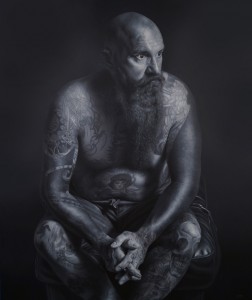

Damien Hirst, Chalford, 2006

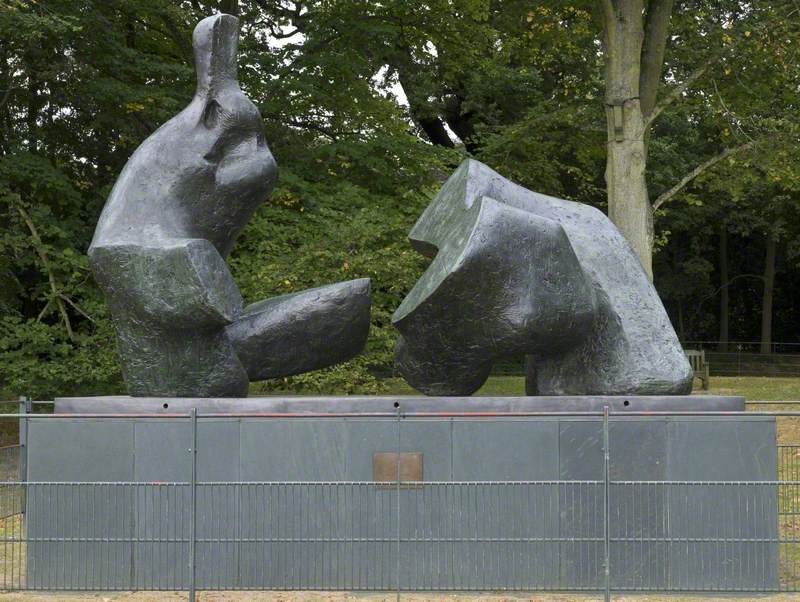

When I visited Kenneth Armitage in his studio in London Olympia in 1993, he made it clear at the beginning that he had very little time, telling me: ’You are still too young, you don’t know what it means not to have enough time’. He was working on what was to become his last large exhibition, a retrospective at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park. My mentioning a meeting with the YSP’s founder changed the situation completely: ‘I’d do anything for Peter Murray’ and I was offered a tour of the studio and a whisky. In hindsight, I wished that I had taken pictures of his studio at the same time. I was too focused on portraits then.

Phillip King, London, 1993

This was not the only experience that got me to pay more attention to artists’ working spaces. Many of the seemingly random objects, the half-finished or abandoned pieces of work can become significant in years to come. I remember a little maquette of a male figure, arms stretched out at a right angle, on a windowsill in Antony Gormley’s studio in 1994. I asked about it and was told ‘that’s the next project’. It was to become the Angel of the North. I wished that I had photographed it in its infant form.

Rachel Whiteread, London, 2001

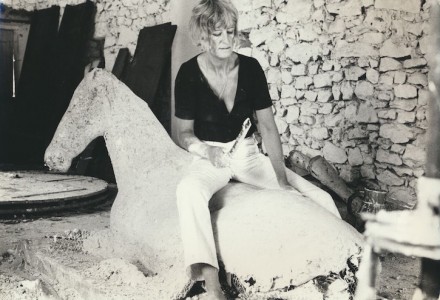

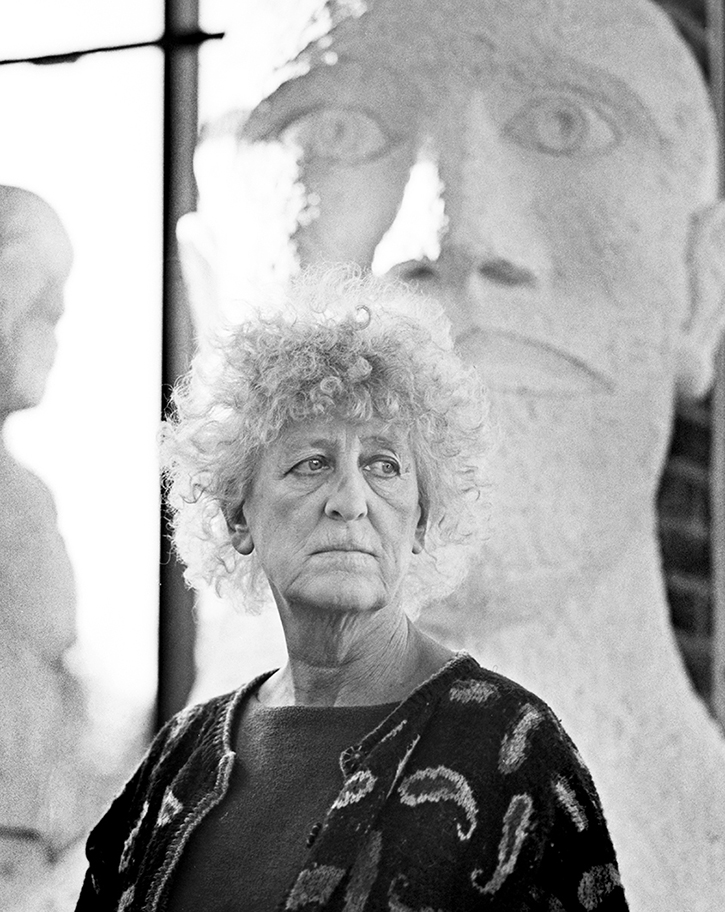

What has changed in recent years is not only my approach to photographing sculptors and their studios. Taking pictures of Dame Elisabeth Frink on 120 black and white and colour negative film in 1993, I could not have imagined that I would one day photograph young artists preparing site-specific installations in her former London studio. Nor could anyone have foreseen that photographers would use a digital SLR as a matter of course and that the term ‘sculpture’ would include works in new media such as David Ogle’s installations with ultraviolet light.

Dame Elisabeth Frink, Woolland, Dorset, 1990

The experience of photographing people who pursue one profession over several decades has brought another dimension to my work as a photographer too, that of time and an interest in documenting artists and their studios beyond a single visit and over many years. It has also led me to a different way of seeing sculptures. I will always think of the person, the ‘human being’ behind it. There is never just an anonymous ‘artist’, but someone who expresses their feelings, their thoughts, hopes and concerns in a form that is best suited for them. It is rewarding to take the time to look at sculptures from that perspective and to look several times for the stories that are hidden in their form.

Anne-Katrin Purkiss, photographer