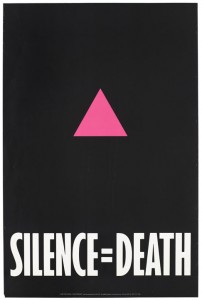

In the last two years, images of doctors and health workers have been extremely prevalent in our daily lives, appearing on TV screens and in newspapers.

Across many cities and towns in Britain, murals to healthcare workers have been created, portraying the NHS and its employees as superheroes in scrubs or soldiers in the battle against coronavirus. How doctors are portrayed in visual culture can tell us a great deal about how medical institutions, practitioners and the public perceive the art of medicine and the role they want it to play in our society.

From the eighteenth to the nineteenth century, Britain witnessed a significant shift in both medicine and in visual culture which translated into how doctors were depicted. The image of the doctor developed from learned scholar or grasping sawbones to public servant, an idea which we still hold true today. An analysis of this shift can throw light on how we have understood medical professionals in the country in the past and how we continue to view them in the present.

Many of the conventions seen in portraits of doctors in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries have their roots in the seventeenth century, when these images began to be produced in greater volume as a professional middle class began to develop in Britain and members sought to cement their status in paint.

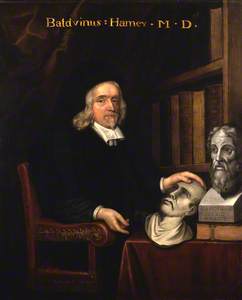

Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century portraits of physicians show male sitters in scholarly settings dressed soberly in black. To the modern eye, many of these sitters could be confused with clergymen. This is hardly surprising as many doctors, like physician Baldwin Hamey, were also trained clerics during this period. His portrait references his profession through the inclusion of a bust of Hippocrates, whose teachings formed the basis of all Western medical knowledge until the late seventeenth century.

Baldwin Hamey, Junior (1600–1676)

1674

Matthew Snelling (1621–1678)

Whilst portraits of doctors from the sixteenth well into the nineteenth century may show medical books, statuary and occasionally medical tools or implements, the sitters are rarely shown dispensing medicine or interacting with their patients. Such depictions provide a valuable insight into the purpose and perceptions of physicians at this time. John Hunter's profession is apparent from the bones, jars, and medical illustrations around him, but his pose emphasises his intellect over the empathy or practical skill we also value in doctors today.

John Hunter (1728–1793)

1786, 1787 & 1789

Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792)

Until the mid-nineteenth century, a rich medical marketplace existed in Britain made up of numerous practitioners, loosely organised into a hierarchy of physicians, surgeons, and apothecaries. Physicians were considered to hold the highest position on this ladder as their profession required university training and scholarly learning.

Physicians prescribed according to received wisdom dating back to classical times and generally refrained from physical examinations of patients. The depiction of physicians therefore as men (women would not be allowed to practice as doctors until 1865), cloistered in their studies, surrounded by books rather than people was fully in keeping with the idea that being a physician was a mental rather than practical pursuit.

Physicians did not want their role to be confused with the manual labour of surgeons, barbers and dentists or the shopkeeping of apothecaries which were considered more lowly professions. Furthermore, they wanted to distinguish themselves from the quack doctors who peddled their wares theatrically in town and village marketplaces.

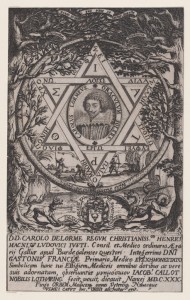

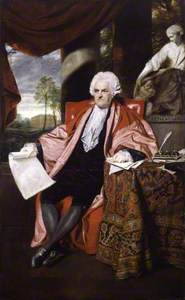

Physicians were often painted alongside other indicators of their wealth, status, and patronage. As the eighteenth century dawned, physicians needed to prove they were not just well versed in medical theory, but were, more generally, enlightened thinkers with knowledge of the arts and other scientific pursuits.

Dr Richard Mead was perhaps one of the most renowned physicians in Britain in the eighteenth century, known as much for his extensive and significant art collection as for his medical practice. Mead was the subject of numerous portraits and busts which often showed him surrounded by objects from his collection.

Building one's reputation as a gentleman as well as a scholar was vital in drumming up business and wealthy clients, something Mead excelled at; he obtained a large personal fortune from his practice. It was at this time that doctors began to adopt fashionable dress in their portraits rather than the sombre black outfits of their predecessors, shaking off the image of the doctor as a cloistered, academic individual.

In his portrait at the Royal College of Physicians, Mead shows himself to be in the company of the great medical men who came before him. William Harvey (who discovered the circulatory system) appears on a shield carried by Athena, the Greek goddess of Wisdom, and Mead points at his own treaty on poisoning now sitting alongside works by Galen, Hippocrates and Celsus. Doctors did not get far, particularly in the eighteenth century, by hiding their light under a bushel.

It perhaps seems surprising to the modern eye that images of medical pioneers, like Edward Jenner, who discovered the smallpox vaccine, are not shown in the throes of scientific discovery but as formal gentlemen.

John Raphael Smith's depiction of Jenner references his discovery through the inclusions of cows in the background of the image (Jenner discovered inoculation by connecting exposure to cowpox with immunity to the more deadly smallpox) but otherwise he is shown as a country squire.

Some portraits like those of the humorist and physician Messenger Monsey portray physicians without any references to their profession at all. Here, Monsey appears in a highly relaxed pose wearing a fashionable silk suit.

Messenger Monsey (1693–1788)

1764

Mary Black (c.1737–1814) and Thomas Black (1715–1777)

When examining the changing image of the doctor over time, there is only so far portraiture can take us. Portraits are never neutral snapshots of individuals in history; their meaning is always entangled with who commissioned them and where they were intended to be displayed. Many portraits of physicians were commissioned from artists for medical institutions such as the Royal College of Physicians or for the hospital or charitable foundations they established. Richard Mead, for example, was an early patron of the Foundling Hospital. As such, medical portraits rarely give us a balanced view of an individual or portray them in a negative light.

The boom of print culture in eighteenth-century Britain, particularly satire, encouraged a greater diversity of voices in visual culture. Prints from this period give us a very different view of the public perception of physicians. What the refined and perfectly posed portraits of physicians do not convey is the wild antics and in-fighting with which many physicians engaged, or the condemnation they received from the public.

The eighteenth century witnessed public fights between physicians and other medical professionals as they jostled for supremacy in the competitive and lucrative medical marketplace. Satire and slander filled the newspapers occasionally leading to duels taking place between some doctors, including Richard Mead.

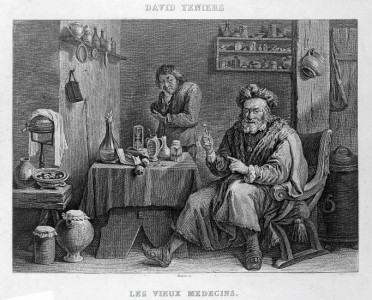

Despite some medical advancements in the seventeenth century, there was little the eighteenth-century physician could do to aid the recovery of seriously ill patients. Physicians' fees were unaffordable for most people and the print culture of this period highlights the widespread reputation doctors had for lining their pockets whilst helping their patients into the grave.

Apothecaries and surgeons were also not immune to these charges. Thomas Rowlandson's scathing satires show apothecaries in league with death itself or cruelly discouraging patients from entering their shops.

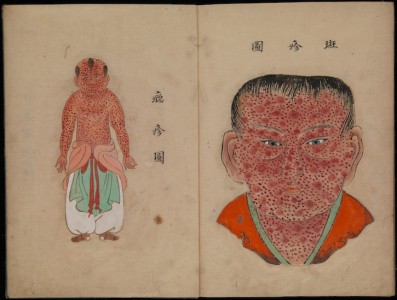

The distrust of doctors was such that even when major medical breakthroughs were made, such as Jenner's discovery of inoculation for smallpox, they were met with ridicule and suspicion.

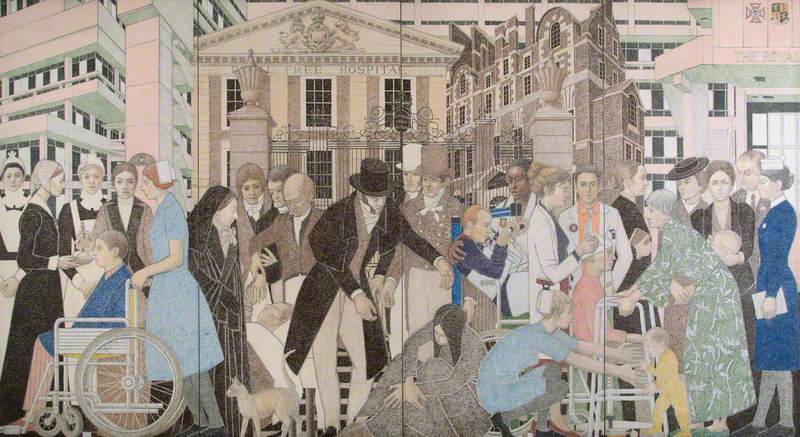

The mid-nineteenth century witnessed a shift in the depiction of doctors in portraits, paintings and prints in keeping with changes in medical practice. From the 1830s, a spirit of reform swept across Britain, something from which the medical world was not immune.

In 1858, the Medical Act was passed, leading to the creation of the medical register, a more institutionalised medical profession and the rise of the general practitioner. The portrait of the scholarly doctor in a rich setting prevailed but the sitter returned to sombre black dress. Perhaps in reaction to the flamboyance of the previous century, doctors portrayed themselves as solid, reliable, and trustworthy. This does not mean that their portraits became any more modest. Swags of red velvet, classical columns and billowing scholarly robes are key components of portraits from this period, continuing to signal the sitter's status and high-profile role in society. In the case of Dr John Ash, a large statue of Benevolence sheltering a child indicates his role in caring for his fellow man by planning the new Birmingham General Hospital.

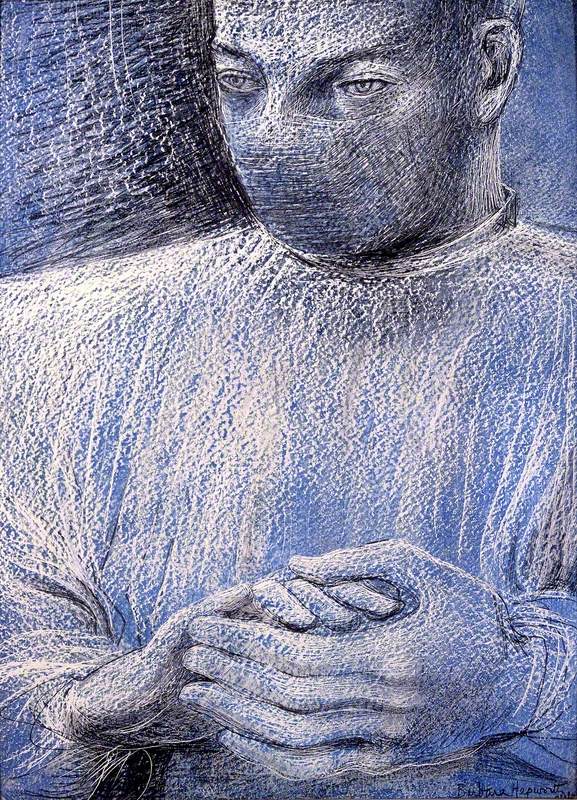

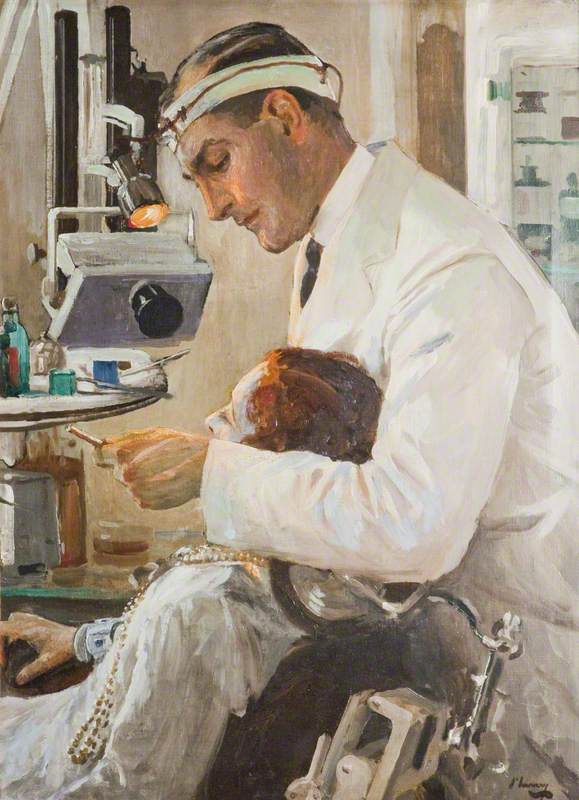

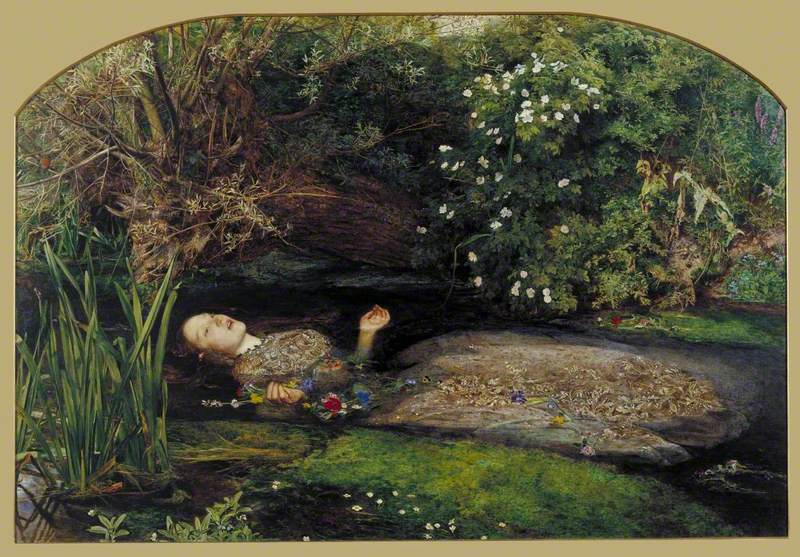

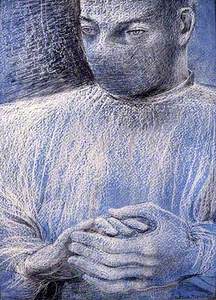

Developments in scientific medicine and professional practice, combined with the Victorian passion for heroism and romance in art and culture redefined the doctor as the dependable hero. Victorian genre paintings of this period show doctors interacting with their patients, often as a comforting presence at the bedside, a new phenomenon. Luke Fildes' The Doctor recalls the professional devotion shown by the doctor present at the death of the artist's son.

The doctor's face is rendered in the greatest detail, his sympathetic concern the focal point of the work. It is in this form of visual culture that we can perhaps see the beginnings of the image of the doctor we might recognise today. As printing and photography allowed for wider dispersal of these images, they could be used to shape and change public opinion but also reflected changing attitudes not just to doctors but to the practice of medicine in general.

The changing image of the doctor throughout history highlights how visual culture works as a vital tool to ascertain how opinions have changed over time. But it also reminds us that behind the image, the reality is often quite different. The portraits in this article might lead you to believe that women played no role in the medical field until the mid-nineteenth century when they begin to be depicted more frequently as nurses and doctors. This simply is not true. Women have played vital roles as midwives throughout history and practitioners of domestic medicine, but such roles were not considered to warrant commemoration in paint.

How doctors are portrayed in visual culture over time gives an insight into how our society's perception of healthcare has changed. When looking at depictions of doctors and nurses in our daily lives, it is interesting to look beyond the immediate image to examine what they say about society's wider response to health. The depictions may look drastically different from those of the past, but they are linked by the same fundamental concerns: when we are at our most vulnerable, to whom should we trust our wellbeing?

Jane Simpkiss, Art Curator at Leamington Spa Art Gallery & Museum, and curator of the exhibition 'A Picture of Health: Art, Medicine & the Body'