Sometimes in portraiture, we see the same faces again and again... and again. Whether they are the sitter, muse, or the artist exploring self-portraiture, the repetitive image of a face holds a curious effect in art history.

Not unlike the artificially intimate (or parasocial) relationships we find in today's media, these faces become embedded not just in our minds, but more broadly in culture itself. While a one-off image may stand out, the repetitive use of one identity in art takes on a mythology of its own. Why is this? What is the motivation for repetition? Do we feel the psychology at play in art collections when we encounter a familiar face on repeat?

At a political level, repetition of the self in art has power advantages. Take the great Elizabethan rivalry between Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester and William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley. These two titans of the court of Elizabeth I jostled, plotted, and counterplotted against each other for decades locked in a power struggle.

In the complicated emotional web of the queen's reign, each held a different sphere of influence. The elder statesman Cecil was a stalwart councillor of the queen and affectionately nicknamed her 'spirit'. He is depicted in sober sixteenth-century Protestant black by this unknown artist of the Anglo/Netherlandish school in the National Portrait Gallery.

Dudley, tellingly referred to as the queen's 'eyes', was her dashing romantic interest and courtier. In this portrait by an unknown artist, he is pictured vividly handsome in gold and red – his machismo body language conveys a tantalising swagger.

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley 1560s (?)

Anglo/Netherlandish School

National Portrait Gallery, LondonAs each vied for political and personal influence in court, the battle played out visually in art. Both Cecil and Dudley are arguably second only to the queen herself as the most represented faces in Elizabethan portraiture. Multiple and diverse portraits of both existed across their political lifetimes and rivalry. One upmanship? Propaganda and overt display of power? Vanity and male privilege perhaps? Consider here that each man possibly used art to compete with the other.

The repetitive self in art history can be weaponised politically and goes beyond just self-expression. The legacy of this rivalry is a visual familiarity for us today – two people we have never met stare back at us from gallery walls, books and websites, occupying a recognisable place in British history, permeating our lives with their faces hundreds of years later.

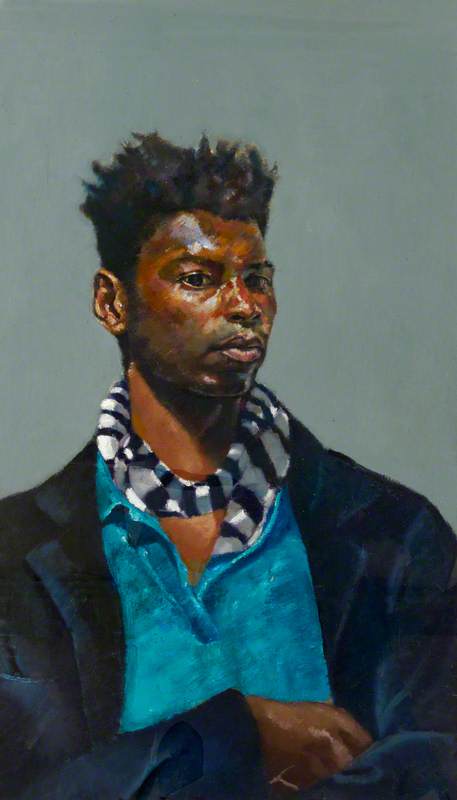

Repetition can also be personal. To record our likeness is a powerful motivator for self-expression and understanding. As the adage goes, 'our favourite subject is always ourselves'. Few artists demonstrate this with such tenderness and searing intimacy as Rembrandt in self-portraiture across a lifetime.

From the youthful Self-Portrait Aged 22 to Self-Portrait with Two Circles, the artist takes us on a journey that's intense and intimate.

Image credit: Simon Gillespie Studio

Self Portrait at the Age of 22 c.1623–c.1629

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669) (studio of)

National Trust, Knightshayes CourtAs a young man, we meet Rembrandt with an open expression, raised eyebrows, deep searching eyes and luxurious brown hair catching a dappled light. Strength and uncertainty vie in this face, eyes deliberately seeking us out and holding our gaze. Does this go beyond just an expression of technical virtuosity? Rembrandt wants to be seen and hold space. Is he looking to us, or back at himself?

Move forward in time across the many iterations of his self-portrait and we watch a life in stop motion.

Self-Portrait with Two Circles retains the earlier background palette yet expands on this almost into abstraction. Gone is the earlier open expression, softened and weathered by time into a more complex series of shapes and textures. The face, however, still seeks us out.

A lifetime later we meet a man altered. The hair is still luxurious, finding the light this time in hues of silver. But the face wears an updated life story. In Rembrandt's case, a life of civic status, early wealth leading to declining fortune and uncertainty, deep grief and loss within his own family, and a society shifting and shaped by war. We can track Rembrandts biography quite literally across his face thanks to the repetitive self. The need to see, be seen, and document ourselves is a powerful urge well known in social media today.

Perhaps repetition can be seen as practical? Artemisia Gentileschi, who stands out as the most celebrated female artist of the seventeenth century, deliberately preserved her own image as a functional expression of purpose within art history.

Here we meet Artemisia in the guise of Saint Catherine of Alexandria, resting on the wheel which caused her so much torture and suffering.

Image credit: The National Gallery, London

Self Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria c.1615–1617

Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1654 or after)

The National Gallery, LondonClose to her breast and heart is held the palm leaf of martyrdom, her clothing a complicated collection of fabrics and textures, positioning her both within seventeenth-century fashion and simultaneously as timeless.

Gripping the vehicle of so much pain, Saint Catherine via Artemisia is a masterpiece study of resilience. Flesh and hue tones display a deep humanity, her knowledge of self gifting us a breathtakingly beautiful study of the body.

Add the layers of emotion onto this – Catherine/Artemisia stares back uncompromisingly (stoically perhaps?), her strength matched with a simmering emotion in the eyes. Where does the story of Saint Catherine start and the artist end, in this depiction?

Practicality is one way in which the genre of the repetitive self helps us understand its power. Put simply, it made sense to use her own image. Her selection of self-portraits has arguably left us a rich example of necessity. As a woman, Artemisia had less legal, financial, and social freedoms than a man in the seventeenth century, possibly making artistic autonomy and life studies more challenging. It's relatable to rely on what you have – yourself.

On a deeper level, the repetitive self is an act of brand control. To use your own face is to get the message out about yourself. The repetitive self in art is one of the greatest examples of artists marketing themselves, finding and holding space, and for their own image to infiltrate elite spaces often denied them.

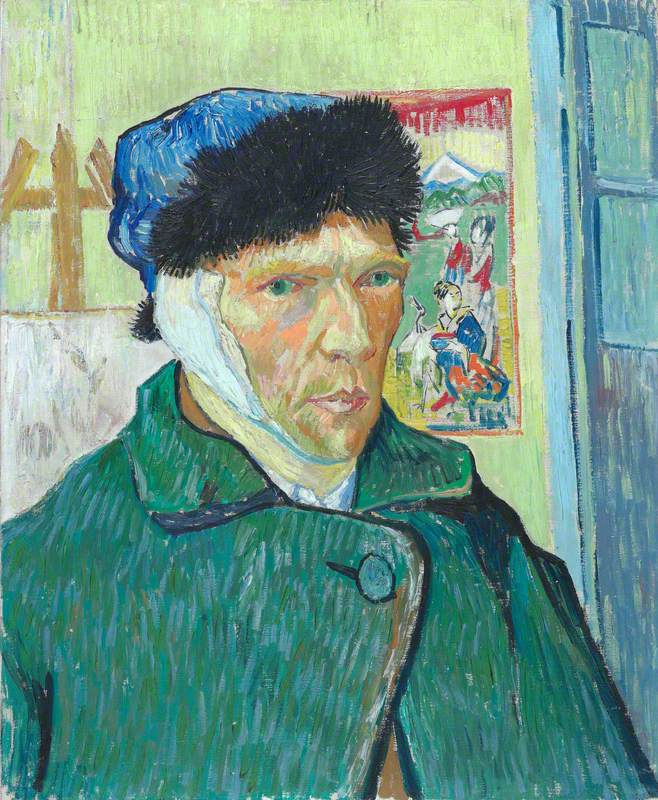

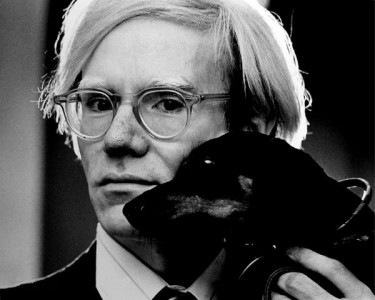

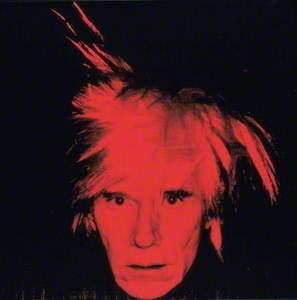

Move forward in time and twentieth-century artists such as Andy Warhol explored the commercialised repetitive self. Repetition is financially highly valuable. Whilst the appearance of some artists is a mystery to us, arguably Warhol leaps out to us as familiar face, and therefore as commercial asset.

The artist consciously played with appearance and self-portraiture. Warhol immerses himself in exploring the cult of celebrity, returning repetitively to himself and others in search of ego, fame and commercialism. Seen here a year before his death, Warhol becomes frozen in one of his last and most enduring self-portraits.

The experimental pop artist of the 1960s has grown to be a celebrity in his own right, startling us in tones of blood red and black. The hairpiece is recognisable to the point of parody, with later homage focusing on this characterisation.

Would you recognise his image without seeing Warhol's name? Can you picture other artists you'd recognise from their face before you remembered a name? Perhaps we have the repetitive self to thank for that.

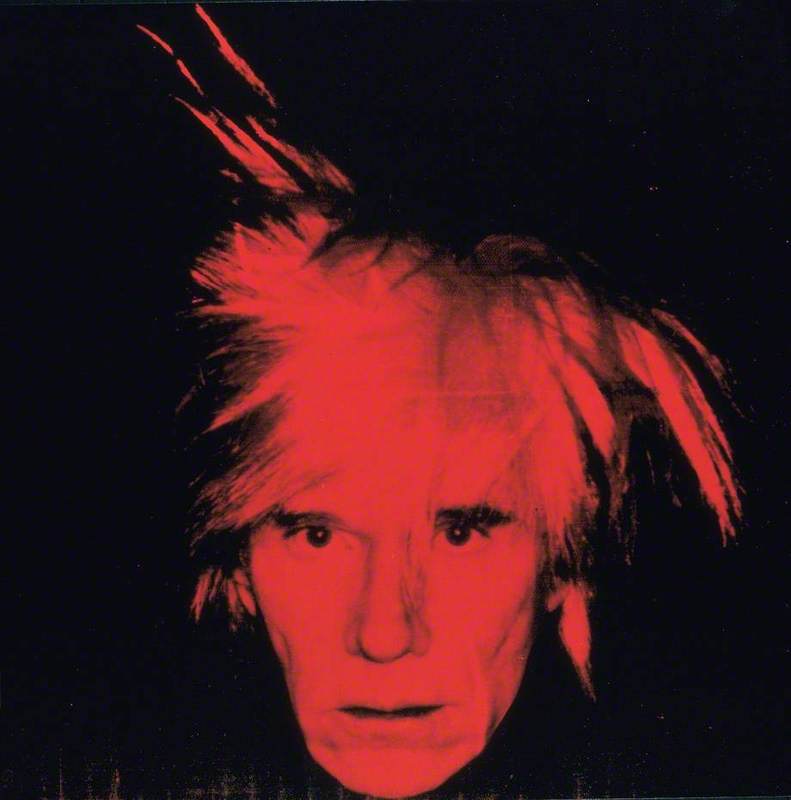

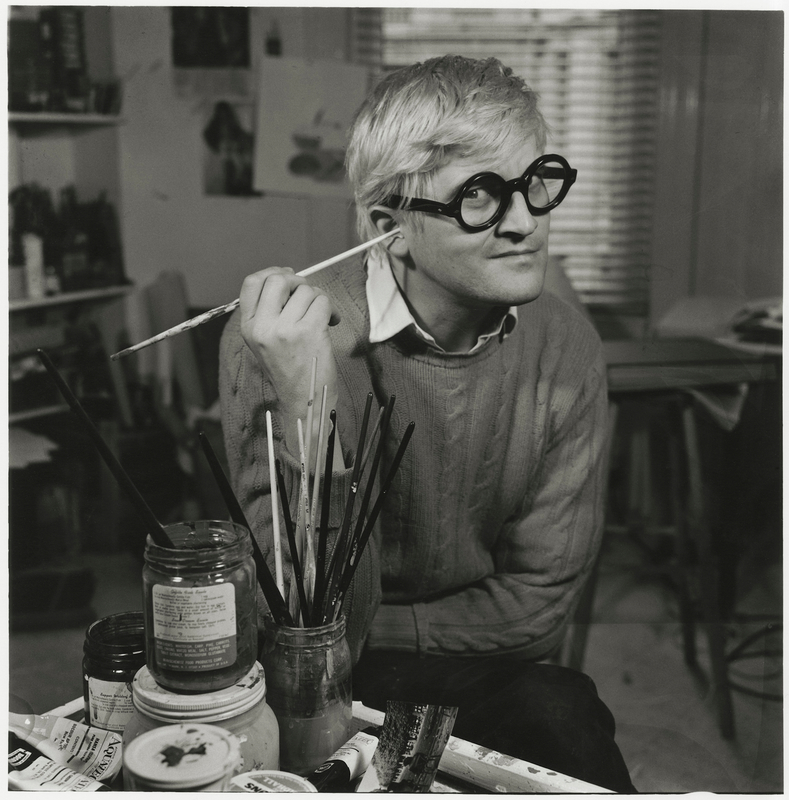

David Hockney, too, has playfully used the self-portrait to shape our perception of himself in the art world. His physicality, relationships, styling and in some cases the act of smoking seen in repetition extends our view of his personality across a career.

An example here is the 2020 National Portrait Gallery exhibition 'David Hockney: Drawing from Life'. It featured new works from the artist where Hockney included self-portraiture, visually updating us on his life.

We age with the artist in a literal sense – his ageing mirroring our own as we grow with him, providing a deep humanity and connection. This is particularly powerful given the artist's queerness, and his work covering the period both before and after the partial UK decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1967. To hold visual space within historical marginalisation is an intensely meaningful act.

Perhaps though, one of the most telling manifestations of the repetitive self in art is what you don't show. Dorothy Mead was a dynamic artist active during the mid- to late twentieth century. Mead developed a haunting, fluid, and deliberately vacant sense of self-repetition in portraiture.

© Val Long. Image credit: A David Bomberg Legacy – The Sarah Rose Collection at London South Bank University, Borough Road

Dorothy Mead (1928–1975)

A David Bomberg Legacy – The Sarah Rose Collection at London South Bank University, Borough RoadThe sheer effort of pinning her appearance down is telling – broad and layered strokes blur our vision. The artist plays with us – offering a deeper detail in some parts of the composition, yet when we reach the face both gender and identity is often evasive.

An artist known for a distinctive self-style in her appearance consciously denies us this in her own artwork. Mead is recognisable by her absence – an absence on her terms that becomes a hallmark. In art history, the repetitive self is such a powerful force that our expectation of the self-portraiture can redefined by it.

The self on repeat is never accidental. It's a necessity in some cases, crafted and politicised with detailed intent. In our contemporary age, we are somewhat desensitised to the privilege of seeing ourselves again and again. Often multiple versions of ourselves are captured in a single day without us even knowing (or consenting).

Yet in art history, the image of self was sometimes radical, thrilling, and unusual. Having just one likeness of yourself was a huge luxury – imagine the distinction of seeing a face in repetition.

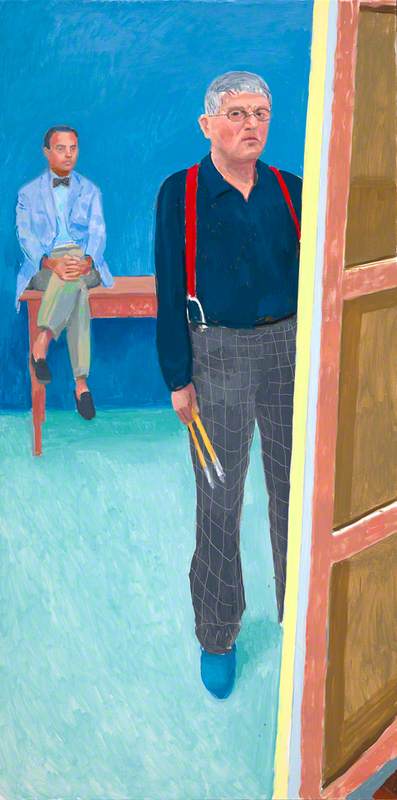

The repetitive self in art continues today – for example, as seen in the beautiful work of artist Desmond Haughton – where and how will it develop next?

Jon Sleigh, freelance arts educator and writer

Enjoyed this story? Get all the latest Art UK stories sent directly to your inbox when you sign up for our newsletter.