When sugar first arrived in Britain in the twelfth century it was consumed as a spice, preservative, and most importantly, a medicine. In fact, so useful was sugar in the medicinal practices of Europe that until the 1900s the expression 'like an apothecary without sugar' came to mean a state of utter desperation or helplessness.

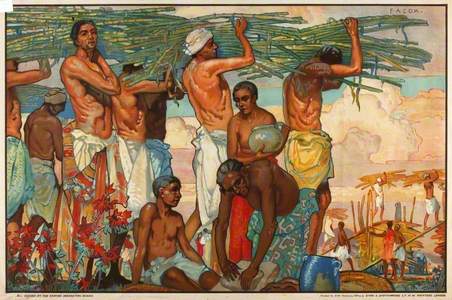

Reaping Sugar Canes in the West Indies

Frank Newbould, Waterlow and Sons Ltd, Her Majesty's Stationery Office (HMSO)

Sugar as a sweetener seems glaringly obvious to us, but the shift from medicine and spice to ingredient and after-course was historically important because sugar consumption in Britain grew exponentially when this became economically possible.

Sugar Cane (Saccharum officinarum)

unknown artist

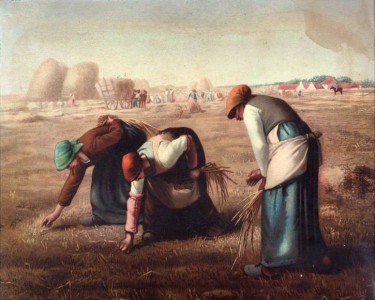

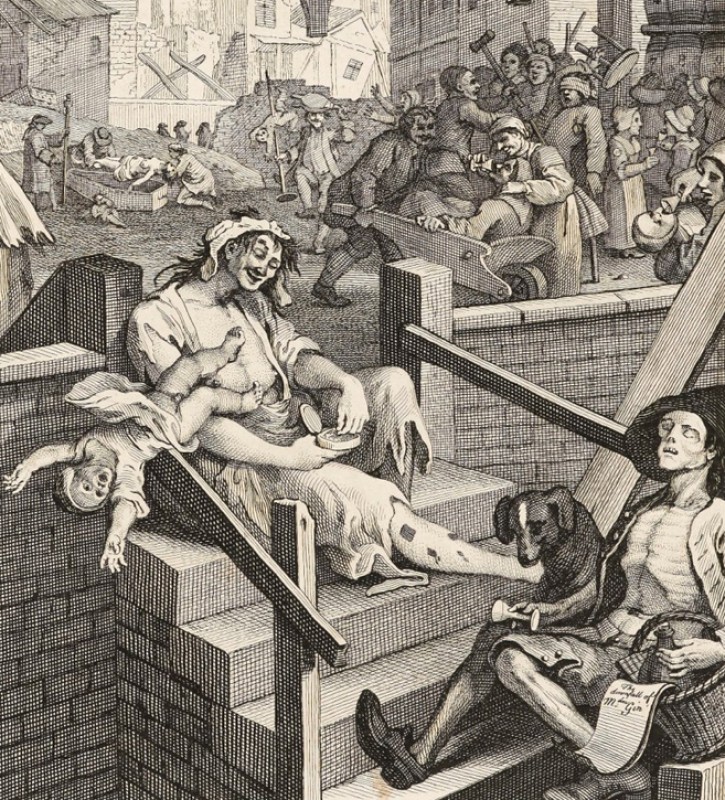

Sucrose from sugar cane is the primary source of sugar in the world. Early refining methods involved grinding or pounding the sugar cane in order to extract the juice, and then boiling down the liquid or dehydrating it in the sun to yield sugary solids that looked like gravel. This process was later replaced by the sugarloaf method – a technology for refining sugar, which was developed and dominated by European powers.

This engraving from the British Museum's collection is part of a series of prints from c.1600 that showed new technologies – in this case, the method for refining sugar. However it's a fabricated image, as in reality the sugar cane fields you see in the background were likely miles away from the refineries. These two parts of sugar production were kept separate, as it was the refining of sugar that transformed it from exotic crop to powerful commodity.

Sugar's role as a status symbol was the driving force behind its commodification. More than an ingredient, throughout the early modern era, sugar was an artistic medium of tremendous influence and impact. The splendour of the dessert course was intensified by the costly nature of sugar, both in the specialised labour required for its intricate execution and the expense of the raw material itself. A sugarloaf – like the one pictured in the painting above – would have cost an average person's monthly salary and that was before the confectioner had even begun their work.

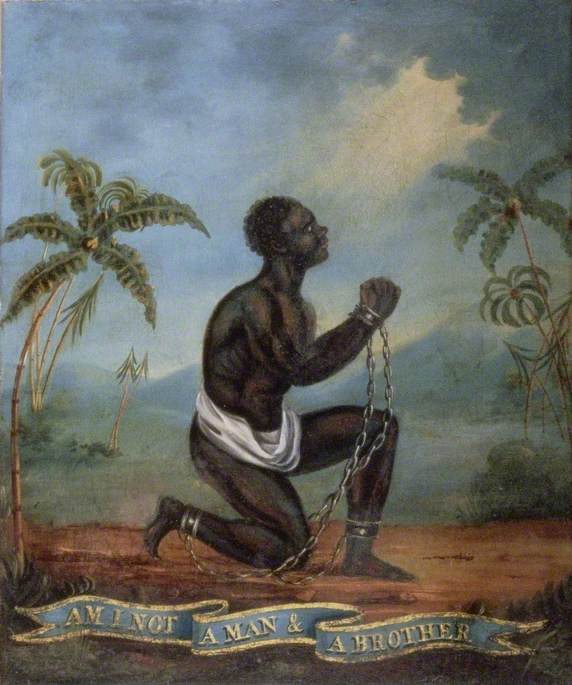

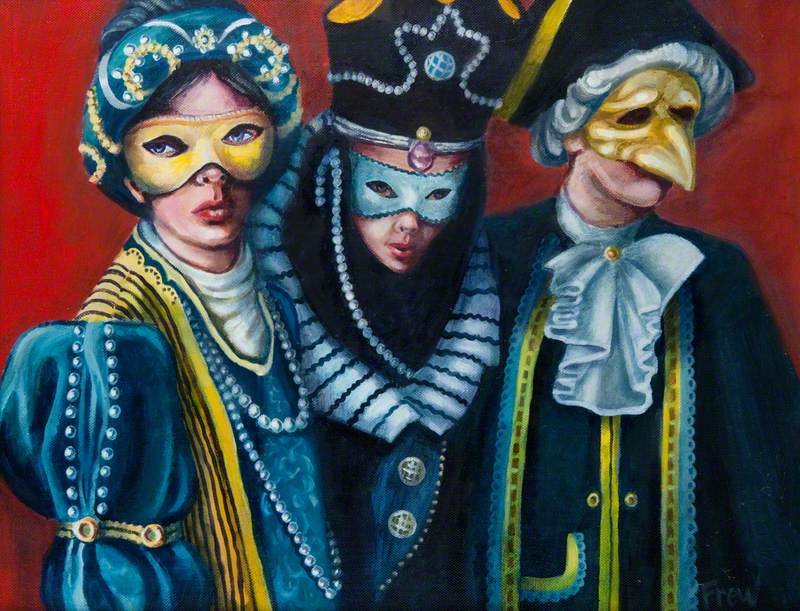

From the fifteenth to the eighteenth centuries, confectioners were treated as artists, with a higher social status than many of their chef counterparts. The fantastical banquets that graced the tables of Europe were the beautiful face of a hideous practice that saw their raw materials prized above people. As tables groaned with the weight of sugarcoated luxuries, in the cane fields of the Caribbean and in the bows of ships there was a very different narrative unfolding.

The essential image of early modern sugar is not one of luxury, but of the horrors of slavery – the transatlantic triangle that saw enslaved people treated as objects, and goods appreciated over individuals, was the direct outcome of the desire for affordable sugar. In their work, Captured Africans, Kevin Dalton-Johnson and Ann McArdle comment on this history.

The public sculpture, which resides in Lancaster, is a reflection of the unjust hierarchy of the past: on the top level, a layer of coins representing the triumph of trade, while at the bottom a cross-section of a slave ship sails across a mosaic Atlantic ocean. This history of sugar should never be forgotten but addressed and engaged with. These choices are part of British history, part of the fabric of our cities and still have contemporary resonance in our food choices and the human cost of consumption in the west.

For a more in-depth look at the extent of Britain's involvement in the transatlantic slave trade, I would recommend UCL's Legacies of British Slave-ownership project, which has catalogued over 61,000 owners of enslaved people. As a country, our participation in the slave trade was widespread, a fact that must not be neglected just because the enslaved people owned by these British proprietors were thousands of miles away on plantations in the Caribbean.

The tumultuous histories of sugar are something that many contemporary artists have engaged with. However, there's one work in particular, which exposes the multifaceted stories of sugar to supreme effect: Kara Walker's work A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby. This monumental, sugarcoated work reflects on the colonial history of this material and the oppression of enslaved people.

The central figure is in the style of the 'mammy' caricature, used so often in history to belittle black women. Meanwhile, the sphinxlike form is an icon of civilisation, but also of ruin. It reminds us of ancient worlds and new beginnings. The iconography is powerful, but more so because it's a subversion of a figure of suppression into one of strength.

The installation is also special because of its location, a decommissioned sugar refinery. The walls are imbued with charged histories and dripping in molasses. The sweetness that is in the air as you enter the space is inviting at first but soon begins to turn your stomach as the gravitas of the narrative sets in. Delight turns to disgust and awe into disquiet, such is the power of the duality of sugar.

From medieval luxury and artistic medium to its role in the slave trade and the current anti-sugar rhetoric, our relationship with sugar has been complicated, to say the least. But it's because of this turbulent history that sugar is such a powerful medium. On a human level, we will forever be drawn to the sweet stuff – sugar is a key ingredient in childhood memories, a taste of nostalgia and delight. The intensely private rituals of confectionery mixed with the social and political history of sugar give us new avenues to explore.

Sugar is a storyteller, it can decay but also preserve – its stories may be hard to swallow but they are there waiting to be articulated, divulged and digested.

Tasha Marks, food historian, artist, and founder of AVM Curiosities