In an interview with Artforum in 1965, Helen Frankenthaler (1928–2011) advised: 'looking at my paintings as if they were painted by a woman is superficial, a side issue... like looking at Kline's and saying they are bohemian. The making of serious paintings is difficult and complicated for all serious painters. One must be oneself, whatever'.

Somewhat ironically, Frankenthaler – who didn't embrace the feminist label – found unprecedented freedom and success as a woman artist. Yet, in spite of her reluctance to discuss the role of women artists, the question of gender has nevertheless come to frame her career.

For six decades, Frankenthaler was a leading exponent of American Abstract Expressionist painting and she is often regarded as a bridge between the first and second generations of the movement, the latter of which was known as the 'Colour Field' group, a term coined by art critic Clement Greenberg.

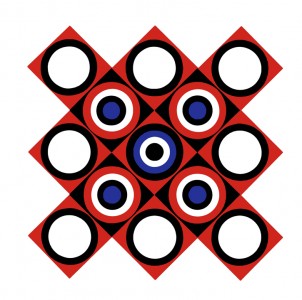

Although not all artists embraced the label, the Colour Field group included Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Clyfford Still, Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, Ellsworth Kelly, Frank Stella and Frankenthaler.

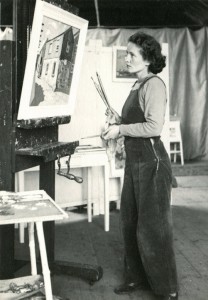

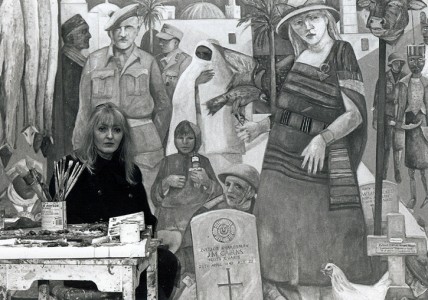

American abstract expressionist painter Helen Frankenthaler in her New York City studio, 1964 #womensart pic.twitter.com/aNzkMrxrJ2

— #WOMENSART (@womensart1) May 14, 2016

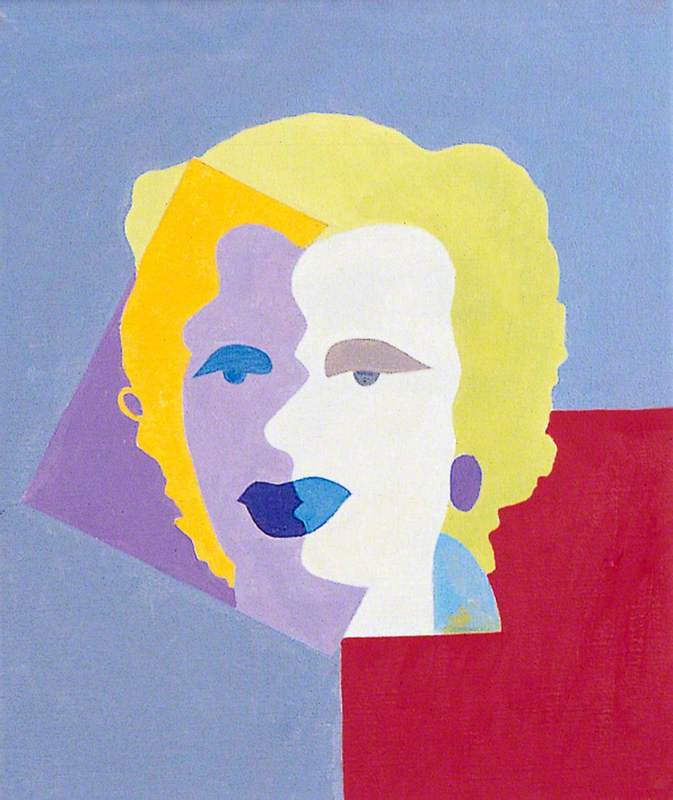

Frankenthaler's abstractions varied from stained, pastel washes (she is credited with inventing the 'soak-stain' technique), to bold, gestural pieces adopting intense and contrasting hues of sharp, primary colours.

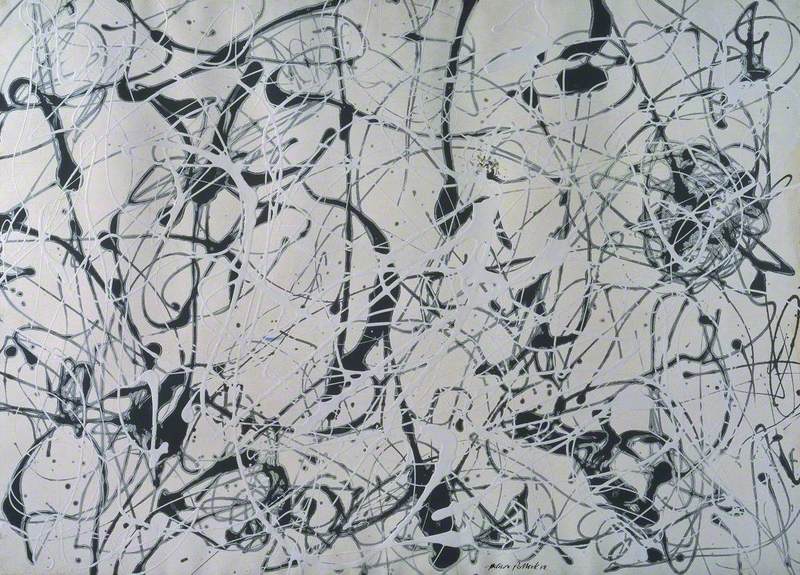

As a young artist, she was inspired by Cubism, Arshile Gorky and Joan Mirò, but was also influenced by those she became acquainted with early in her career – figures such as her teachers, the Mexican artist Rufino Tamayo, Hans Hoffman and of course, Jackson Pollock – whose technique of drip painting and working on a large canvas placed on the floor she adopted.

Unlike her male contemporaries of Abstract Expressionism, Frankenthaler introduced a novel form of whimsical lyricism to her paintings. But 'lyrical' became a loaded word for the artist, especially as critics continued to ascribe her softer style to her femininity, which she felt belittled her work. Particularly in the 1950s and 1960s, critics commented on her 'seductive' and 'delicate' feminine palette, sometimes making sexual analogies to her painting process.

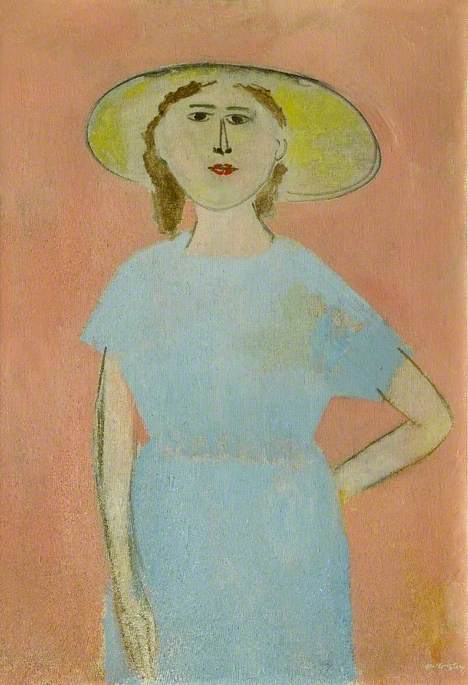

Blue Form in a Scene, 1961 #americanart #frankenthaler pic.twitter.com/VyCAqWSY2v

— Helen Frankenthaler (@h_frankenthaler) December 2, 2020

Perhaps to prevent such gendered readings, Frankenthaler evaded questions about her role as a woman artist and distanced herself from feminism. Her husband and fellow painter Robert Motherwell once simply stated that 'her lyricism as an artist comes from a great personal inner liberation.'

One of Frankenthaler's former gallerists, Andre Emmerich, declared that her work 'began to be appreciated for its lyricism and strength', but despite achieving substantial success 'she continued to be regarded as a woman painter and therefore not quite in the same league as the male heavy hitters of her generation.'

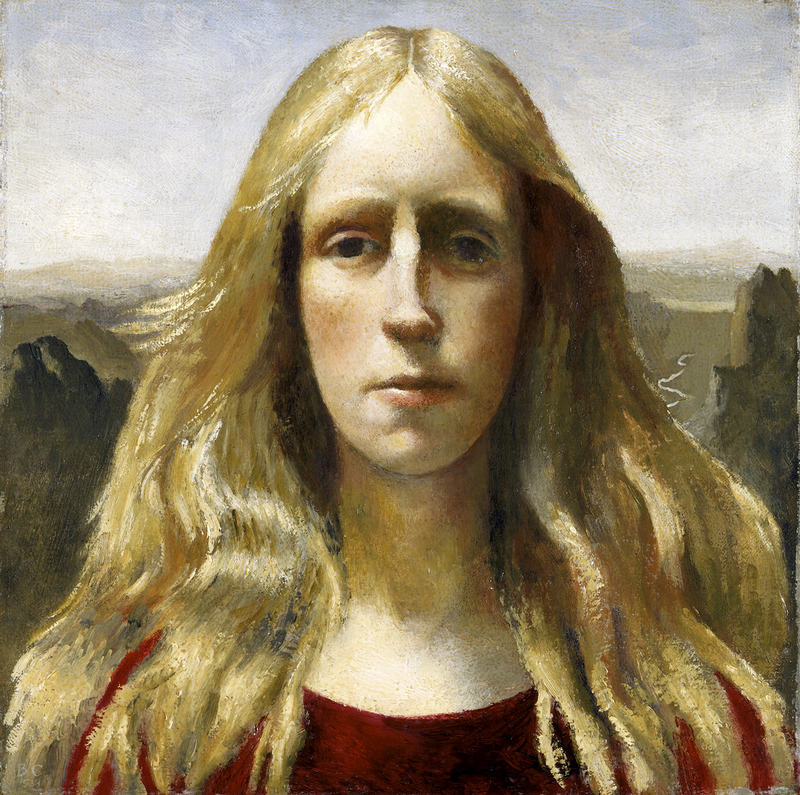

The conflict over what role gender played in her art persists today. It is generally agreed that Abstract Expressionism thrived from a particularly masculine and 'heroic' narrative, embodied in the figure of Pollock more than any other artist. Hans Hofmann infamously paid Lee Krasner (the partner of Pollock) a backhanded compliment in 1937, when he said about her work: 'this is so good, you would not know it was done by a woman.'

The conflation of the female identity and aesthetic taps into Linda Nochlin's observation that women artists were quickly pigeonholed and perceived to be 'more inward-looking, more delicate and nuanced in their treatment of their medium.' In fact, Nochlin had directly challenged the view that Frankenthaler's work – painted on giant canvases – was 'dainty' or 'introverted'.

Though Frankenthaler was directly and deeply influenced by Pollock (she described her first encounter with his work as 'a beautiful trauma'), she was not merely a follower. Her idiosyncratic style of abstraction and pioneering approach to both colour and form rightfully cemented her as a central figure of Abstract Expressionism.

Emerging in New York in the 1940s, the Abstract Expressionist movement shared the belief of the critic Clement Greenberg that modern painting should embrace two-dimensionality and abstraction – without reference to the external world that was increasingly defined by (what Greenberg described as) a 'kitsch' consumer culture. A vehement supporter of Pollock, Greenberg later championed painterly flatness and the 'all-over' gestural composition.

In his essays from 1955, 'American-type painting', Greenberg failed to mention Frankenthaler, while he praised her future husband Motherwell as 'the least understood, if not the least appreciated, of all the abstract expressionists.'

Frankenthaler's omission from his essay is interesting, not only because Greenberg had been in a romantic relationship with the artist for many years, but also because in 1952, Frankenthaler had demonstrated her pouring method (she dubbed the 'soak-stain') personally to Greenberg – a moment that shifted the direction of the movement.

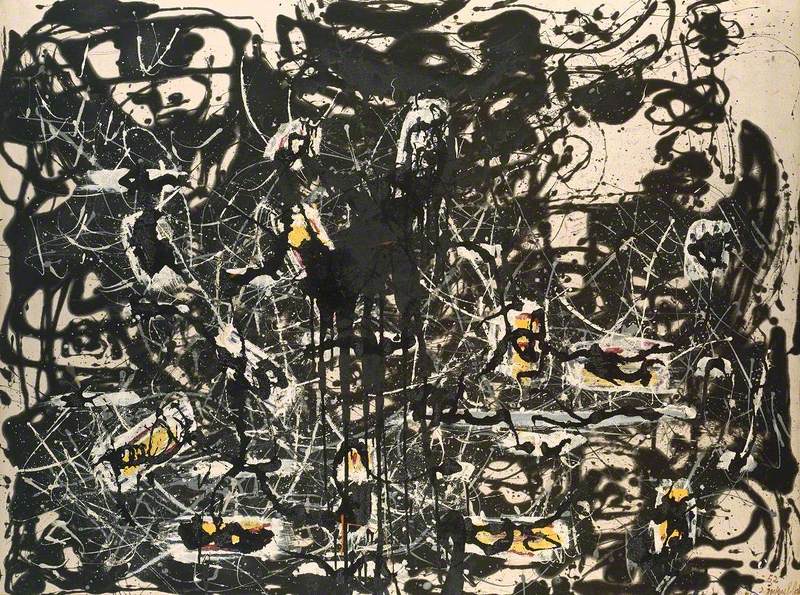

With the encouragement of Greenberg, the painters Kenneth Noland and Morris Louis visited Frankenthaler's studio in 1953. Both artists were immediately impressed by one of her most famous 'soak stain' paintings inspired by the landscape of Nova Scotia, Mountains and Sea.

US abstract expressionist Helen Frankenthaler, Mountains and Sea, 1952 #womensart pic.twitter.com/XeAqM1y3LB

— #WOMENSART (@womensart1) May 17, 2017

Following the visit, they began to adopt her staining techniques. Louis, in particular, experimented by pouring paint onto an unprimed canvas, allowing the liquid to flow, soak and stain according to chance, as seen in his work Alpha-Phi housed in Tate's collection.

In 1956, Frankenthaler was photographed by Gordon Parks for the cover of LIFE magazine. Seven years earlier LIFE had placed Pollock on the cover with the question: 'Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?'

The publicity was testament to her impact, but Frankenthaler had not reached the same level of commercial success as her male peers. Her gallerist Emmerich confessed that: 'For many years I struggled in vain to interest European dealers, curators and critics in Frankenthaler's work. The tide did not really begin to change until the 1990s.'

Because of her marriage to Motherwell between 1958 and 1971, she was often framed as his wife, or as an art society hostess and heiress, diminishing her role as a painter.

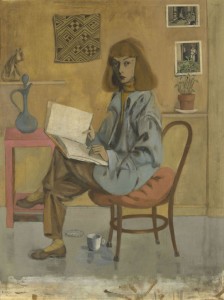

US Abstract Expressionist painter Helen Frankenthaler in the studio, 1956. Photo by G. Parks #womensart pic.twitter.com/gbuuXpkIbM

— #WOMENSART (@womensart1) December 11, 2019

Frankenthaler also continued to receive disparaging reviews that contrasted her style to Pollock's. In 1961, E. C. Goossen wrote: 'Frankenthaler's painting is manifestly that of a woman... without Pollock's painting hers is unthinkable. What she took from him was masculine; the almost hard-edged, linear splashes of duco enamel. What she made with it was distinctly feminine, the broad, bleeding-edges stain on raw linen.'

The reductive evocations of feminine 'bleeding' and declarations of Frankenthaler's indebtedness to Pollock must have been frustrating for the artist, especially as her work had very little resemblance to his.

Between the late 1950s and 1960s, Frankenthaler – perhaps aware of the gendered readings of her work – shifted her palette to incorporate yellows, greens and blues. However, her signature colours were ostensibly warmer tones – bold splashes and swathes of tangerine orange, deep crimsons and bright pinks. In 1962, she had begun painting in acrylic, so as to achieve more richly saturated colours that diverged from her earlier, diluted tones.

Frankenthaler encountered further difficulty when she rejected 'serial painting', which encouraged artists to repeat their signature style. She refused to paint on smaller canvases which were known to be easier to sell, insisting that her work reached its full potential when created on a large scale. This courageous move indicates that she was not prepared to shrink herself or her art.

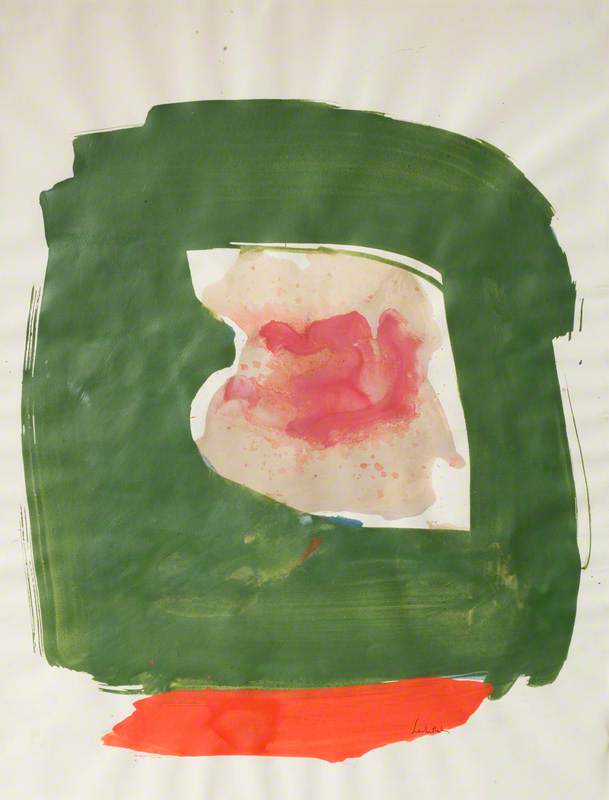

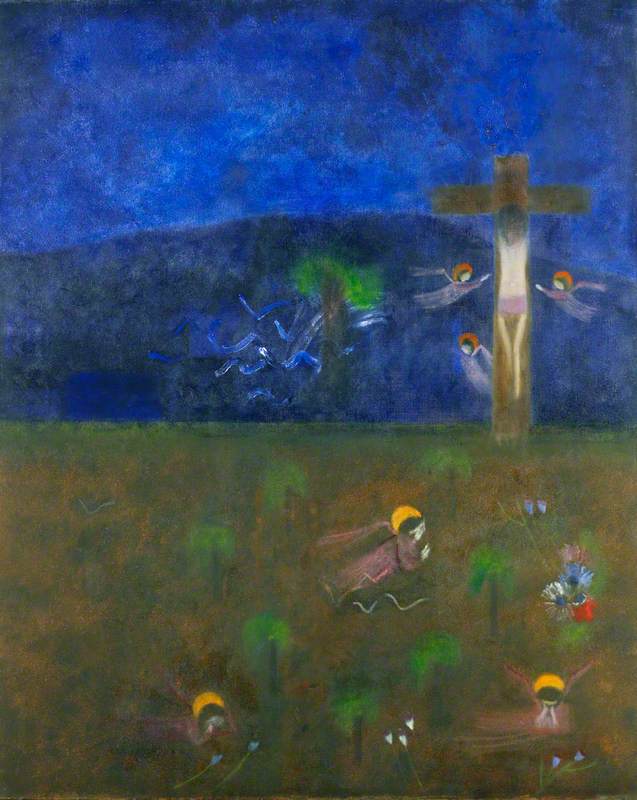

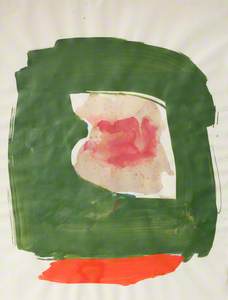

In 1961, Frankenthaler created the work Vessel, one of her signature soak-stain paintings on raw canvas, which is currently on display in Tate Modern. Vessel reflects Frankenthaler's desire to leave 'negative' space on the canvas, which allows the flecks and smudges of colourful pigment to puncture and pulsate on the surface more intensely.

© Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. . Image credit: Jordan Tinker, courtesy Tate

Vessel

1961, by Helen Frankenthaler (1928–2011)

The artist once explained that: '[The] "negative" space has just as active a role as the "positive" painted space. The negative spaces maintain shapes of their own and are not empty'.

Image credit: Tate Modern, London

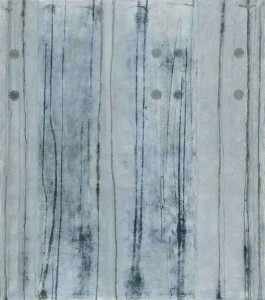

Installation shot of the Helen Frankenthaler display at Tate Modern

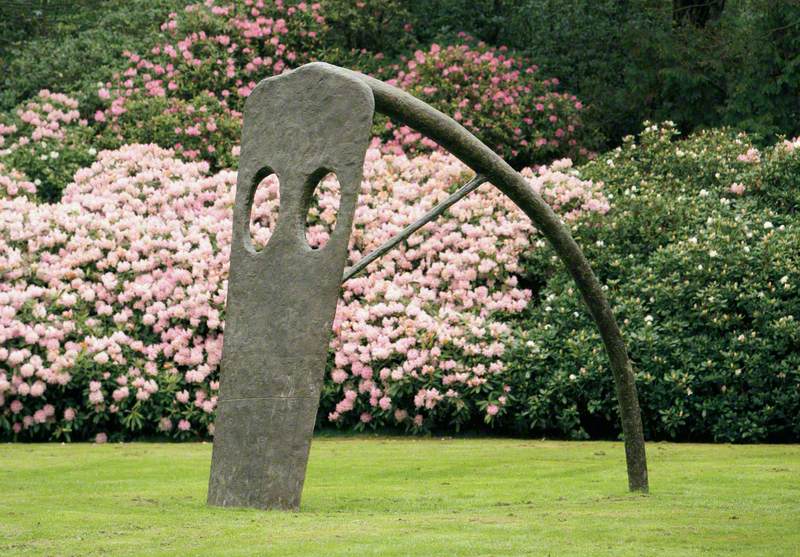

Later in her career, Frankenthaler experimented with new media: lithographs, screenprints, aquatints and woodcuts. In 1972, she created her first sculpture. The following decade, she left her New York studio to work as a set and costume designer for the Royal Ballet, designing for a production called 'Number Three' which was choreographed to Prokofiev's Third Piano Concerto. The work below, housed in Kettle's Yard, Cambridge, was a final maquette used on a set at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden.

© estate of Helen Frankenthaler/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2017. Image credit: Kettle's Yard, University of Cambridge

Helen Frankenthaler (1928–2011)

Kettle's Yard, University of CambridgeFrankenthaler was perhaps not a radical rule-breaker, but she did defiantly and strategically bend and remould the rules, so as to define her own distinct vision. Although she deflected questions about being a woman artist – 'I don't resent being a female painter. I don't exploit it. I paint' – she paved the way for other women artists to be taken more seriously by the art establishment.

The Helen Frankenthaler display at Tate Modern is currently on show alongside four other paintings on loan from the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation.

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK

Further reading

Andre Emmerich, 'Recollections: Greenberg & Frankenthaler', The New Criterion, Vol. 39, No.4, 2004

Mary Gabriel, Ninth Street Women: Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler: Five Painters and the Movement That Changed Modern Art, 2018

Sybil E. Gohari, 'Gendered Reception: There and Back Again: An Analysis of the Critical Reception of Helen Frankenthaler', Woman's Art Journal, Vol. 35, No.1, pp.33–39, 2014

Linda Nochlin, 'Why have there been no great women artists?', in Woman in Sexist Society: Studies in Power and Powerlessness, 1971

Barbara Rose, Frankenthaler, 1972