In 1968 the Arts Council of Northern Ireland (ACNI) presented 'Ulster Painting '68' at their gallery on Bedford Street in the centre of Belfast. The Director of ACNI, Michael Whewell, described it as an 'anthology of current Northern Irish painting', and while it followed a number of smaller survey exhibitions in the late 1950s and 1960s, this was clearly intended to mark the sense of a new beginning in contemporary art and to 'indicate the direction for a promising future'.

Seven years after the first open submission painting exhibition held by the Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts (CEMA, shortly to become the Arts Council of Northern Ireland), which attracted around 300 entries, 44 artists were invited to exhibit at 'Ulster Painting '68', with the requirement, based on the available space, that one large work and one smaller work could be included – a stipulation to which some appear to have paid more attention than others.

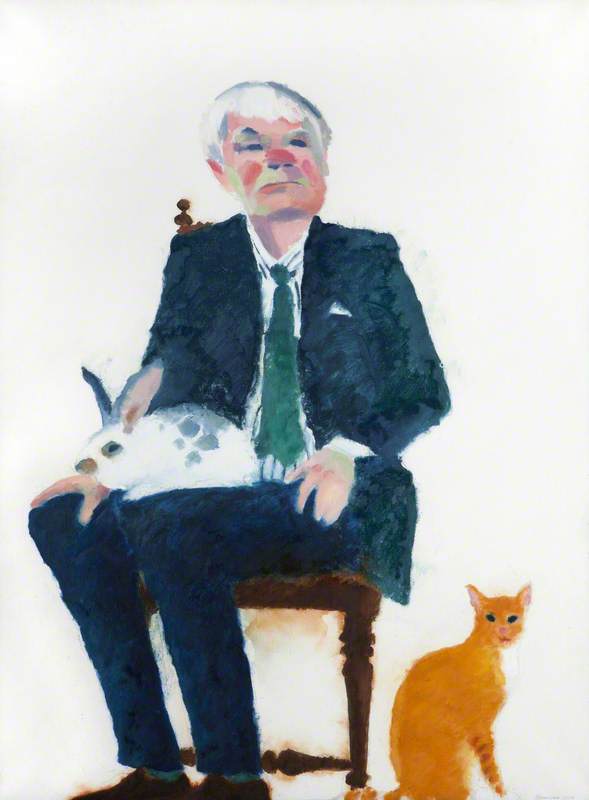

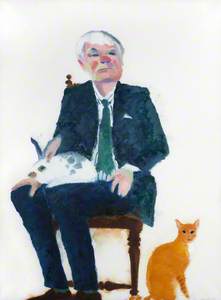

The exhibition might be seen as the meeting point of three generations. The first 'modernist' generation in Northern Ireland, including artists such as Colin Middleton, Gerard Dillon and George Campbell who had mostly made their reputation and career both in Dublin and Belfast, showed here alongside those who came to prominence in the mid-1950s, notably Basil Blackshaw, Deborah Brown, T. P. Flanagan and Cherith McKinstry. A notable proportion of the invited painters belonged to a younger group born during the war or in its aftermath, including Neil Shawcross, David Crone, Brian Ferran, Brian Ballard and J. B. Vallely.

It is a testament to the selectors that virtually all those who would now be regarded as the central figures in post-war painting in Northern Ireland are present. One notable absentee, Daniel O'Neill, was living in London at the time. While there is an undeniable bias towards male artists, with only six women artists invited to exhibit, that arguably reflected a broader issue in art beyond these shores, and it is important to note that some of the most progressive work in the exhibition was made by artists such as Deborah Brown, Kathleen Bell, Alice Berger Hammerschlag and Anna Ritchie.

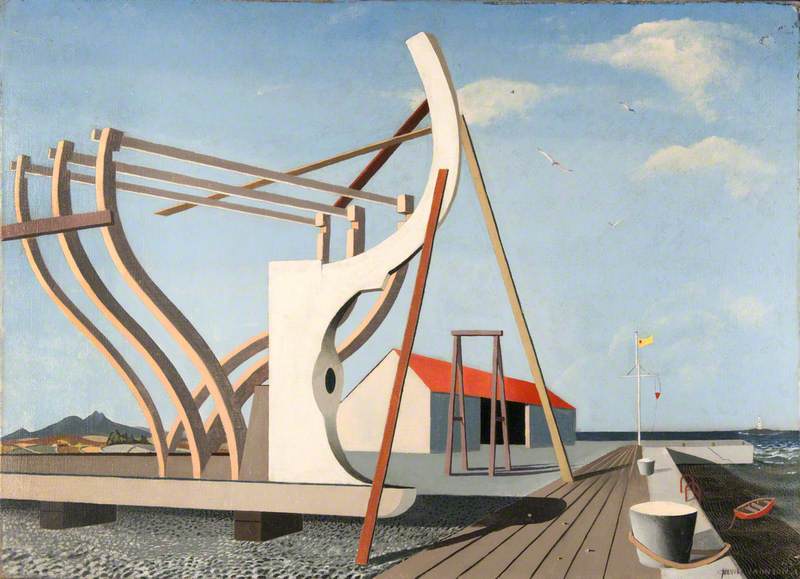

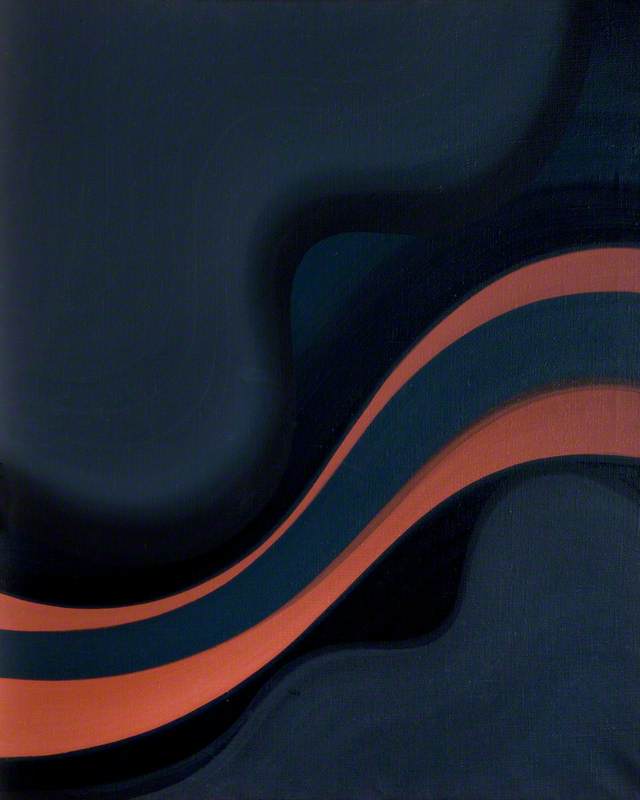

Michael Whewell's introduction to the catalogue noted that this exhibition would demonstrate 'a departure by many from an earlier common preference for landscape forms'. The suggestion of a dramatic shift from this traditional local subject matter is perhaps not quite correct, but there was certainly a radical reinvention of the Ulster landscape as a subject: both in its formal pictorial analysis and the broader conceptual approach to it. This took place between the 1940s – before which the local landscape tradition had remained very conservative, with its most notable exponents James Humbert Craig, Hans Iten and Maurice Wilks – and this exhibition in 1968, a reinvention to which younger artists such as Basil Blackshaw, Malcolm Bennett, David Crone, Richard Croft and T. P. Flanagan all contributed.

Beyond this relationship with local art history, the exhibition reveals a level of interest in contemporary international painting which might be associated with the remarkable collection of post-war art acquired by the Ulster Museum in the decade preceding this exhibition, including paintings by Morris Louis, Helen Frankenthaler, Joan Mitchell, Kenneth Noland, Antoni Tàpies, Sam Francis, Karel Appel and Jean Dubuffet. It is also notable that a number of the artists involved in 'Ulster Painting '68' had come to Northern Ireland to teach, in some cases at the College of Art, or to take up other work. Austrian-born Alice Berger Hammerschlag had actually arrived as an emigré from Europe during the war, so there was an increasingly international scope to the Belfast art scene.

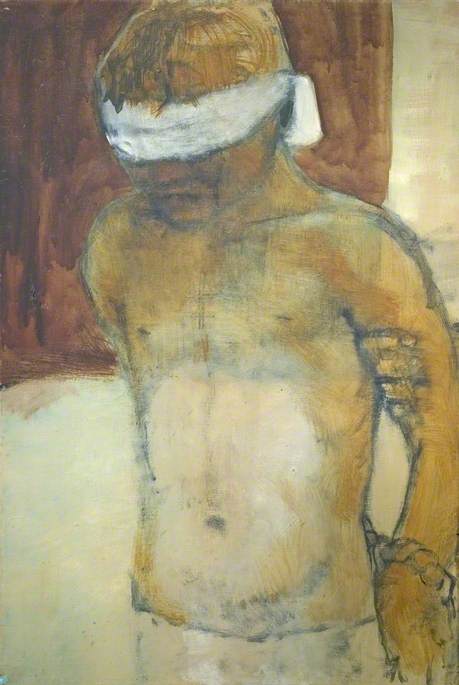

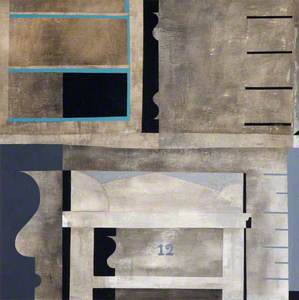

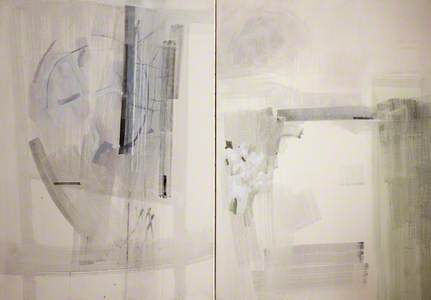

Opposing Rhythms Subsiding

1967

Alice Berger-Hammerschlag (1917–1969)

Despite the innovative ambitions of the exhibition, some of the best-known artists included – such as Colin Middleton, Gerard Dillon, George Campbell and Tom Carr – were more closely connected with pre-war European and British modernism, rather than post-war transatlantic or European developments. In the exhibition, Dillon's melancholy Pierrot, Campbell's post-cubist Tribesmen and Middleton's highly abstracted, textured and incised synthesis of figure and landscape, Cybele – which demonstrates his interest in Ben Nicholson and Victor Pasmore, as well as the cool minimalism of Carr's watercolours – are all revealing of the 'individuality and independence' that Whewell describes.

Middleton and Campbell, as well as Blackshaw, Flanagan, Hammerschlag, McKinstry and Deborah Brown, were the artists picked out from the exhibition by the critic of the Irish News and Belfast Morning News, noting that otherwise, in his opinion, 'few appeal as outstanding works of art'. Similarly, it was the more established artists who were praised by the Irish Times reviewer when the exhibition transferred to Cork in 1969: Campbell, Blackshaw, McKinstry again, and also Arthur Armstrong, Dillon and Carr, as well as Anna Ritchie, at that time married to Blackshaw. The article did, however, describe the 'all-embracing collection' as 'thought-provoking and exciting' and, acknowledging the stated ambitions of the exhibition, agreed that 'in no case can the trend be ignored'.

It is notable that a number of these older artists remain even today among the best-known of all those in the exhibition, particularly the generation of Middleton, Dillon and Campbell, which still largely seems to dominate the canon of modern painting in Northern Ireland.

It might be argued that this is the case in part because this exhibition, and its broader intentions, were overtaken by history. The artistic future towards which 'Ulster Painting '68' had been planned as a marker was dramatically transformed by the events in 1968 that are often considered the beginning of the modern Troubles.

It is difficult to identify and quantify precisely the impact of the Troubles on art in Northern Ireland and the opportunities for artists during that time. In 1967 George McClelland opened his gallery, which exhibited contemporary artists such as Colin Middleton, Daniel O'Neill and F. E. McWilliam alongside older pictures, antiques and objets d'art, while the Tom Caldwell Gallery opened around 1970, to join the existing Bell Gallery, and was soon exhibiting a number of the artists included in the 'Ulster Painting '68' exhibition, notably Colin Middleton, George Campbell, Basil Blackshaw and Neil Shawcross.

With the constant threat of bombs and violence, it was clearly not easy to maintain a business in Belfast that was dependent on collectors visiting. The McClelland Galleries closed in 1974, while the Bell Gallery moved out of the centre of the city in the mid-1970s. An exhibition by the sculptor David Winters at the Arts Council Gallery on Bedford Street, where 'Ulster Paintings '68' was held, was largely destroyed in a bomb blast in the 1990s.

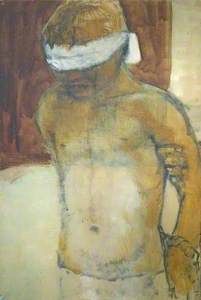

The impact on the art being made in the city was varied and complex. Deborah Brown began to use barbed wire in her fibreglass sculptures, carrying with it an implicit sense of violence, and David Crone's fractured reflections in shop windows and dissolving picture planes perhaps reflect the visual and psychological experience of a city suffering so much at that time from bombing. Jack Pakenham, who exhibited a painting of a nude and a drawing of Ibiza in 'Ulster Painting '68', went on to become arguably best-known for his dark and theatrical paintings that seemed to identify a mood of the period. T. P. Flanagan's Victim (recently acquired by Fermanagh County Museum) was inspired by the shooting of his friend Martin McBirney, while paintings such as An Ulster Elegy maintain his metaphorical approach to the broader events of the time.

Perhaps 'Ulster Painting '68' belongs alongside some of the other intriguing but perhaps frustrating one-off exhibitions that each tried to re-invent the landscape for visual art within Northern Ireland: Hugh Lane's exhibition of modern European art held in Belfast in 1906, the 1934 Ulster Unit exhibition, even perhaps the 1958 exhibition of the Lewinter-Frankl Collection, which brought together major twentieth-century British and Irish artists with recent graduates from Belfast College of Art.

Unlike those, however, it also marked the immediate beginning of a very different time, when one might argue that, for some artists, the perception of their role changed, as well as their relationship to their environment and the manner in which they might maintain a career.

Dickon Hall, Commissioning Editor: Northern Ireland

This article was supported by the Esme Mitchell Trust