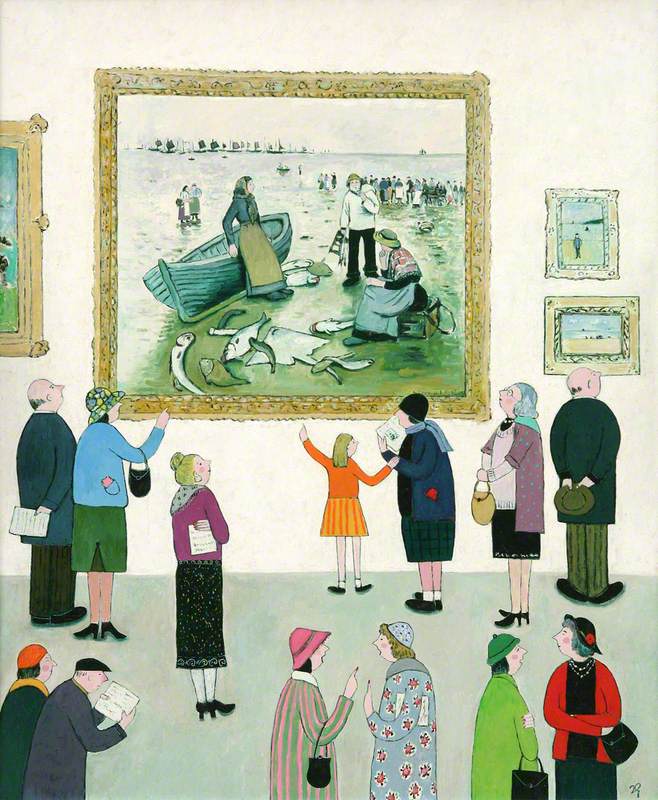

In a 2018 BBC Four programme, Sonia Boyce asked the question Whoever Heard of a Black Artist? – showing the lack of diversity in the traditional canon of visual arts.

The same criticism could be levelled at the canon of composers of classical music. While in recent years there has been some attempt to redress the balance and increase diversity in concerts and recordings, the fact remains that only a handful of composers of colour are cemented into the collective consciousness.

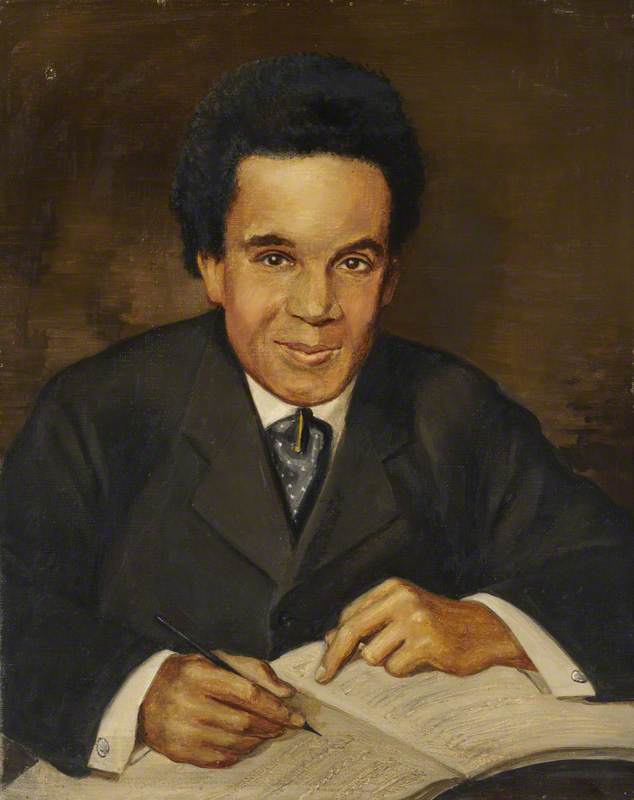

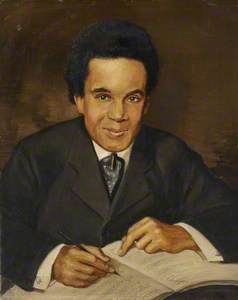

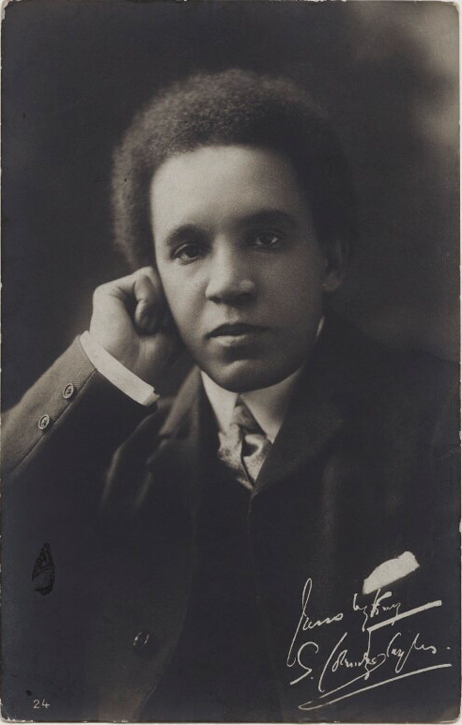

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

c.1905, vintage bromide print, published by Breitkopf & Hartel

The story of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, however, is intriguing and his early death at the age of just 37 is one of the great 'what if' moments of British classical music in the twentieth century.

Taylor was born in 1875 to an English mother and an African father. His mother, Alice Hare Martin (also known as Holmans – her parentage is unclear) was born in Dover in Kent; his father, Dr Daniel Peter Hughes Taylor, was from Sierra Leone. Samuel never knew his father as he returned to Africa when Alice was expecting – it is likely he was unaware of the pregnancy.

The family called the young boy Coleridge – he is recorded by this name in the 1881 census. He was named after (and is not to be confused with) the Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

Coleridge was born in Holborn but raised in Croydon, in what was then Surrey, after his family moved out from central London. There were several musicians in his family, and his musical education began early – he learnt to play the violin from age five, and was tutored free of charge by the local musician Joseph Beckwith.

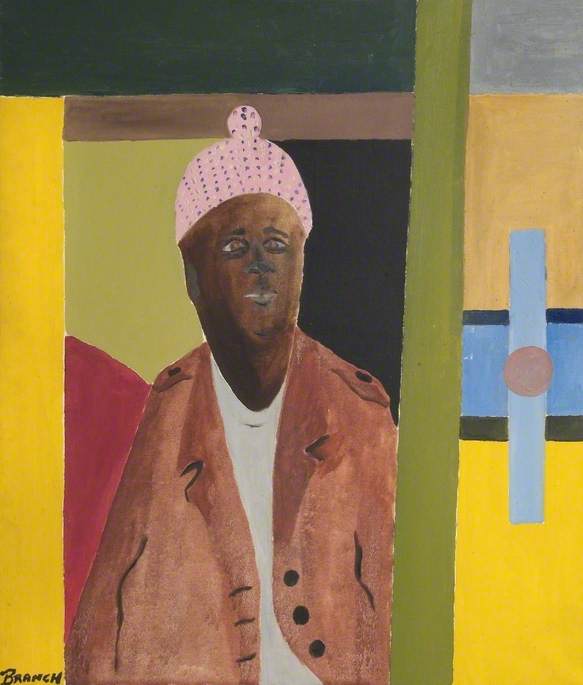

When he was about seven, he posed for painters at Croydon Art Club. One of the paintings produced was by Walter Wallis, who was Principal of Croydon Art School in the 1880s and 1890s.

The young Coleridge is wearing a cap and tunic – possibly artistic licence as his sister said: 'They put a basin on his head and a shawl round his shoulders so he looks a bit African'. This was painted at a time when Black subjects were routinely portrayed by painters as 'exotic' or 'other' – despite Coleridge being born and brought up in England.

This portrait was purchased by the National Portrait Gallery from the composer's family and is a rare example of a child's portrait in their collection. It is a fascinating document of the great composer's childhood.

Around the same time as the portrait was made, Coleridge joined the choir of St George's Presbyterian Church in Croydon, where Colonel H. A. Walters oversaw his musical development and later helped organise his admission to the Royal College of Music in 1890.

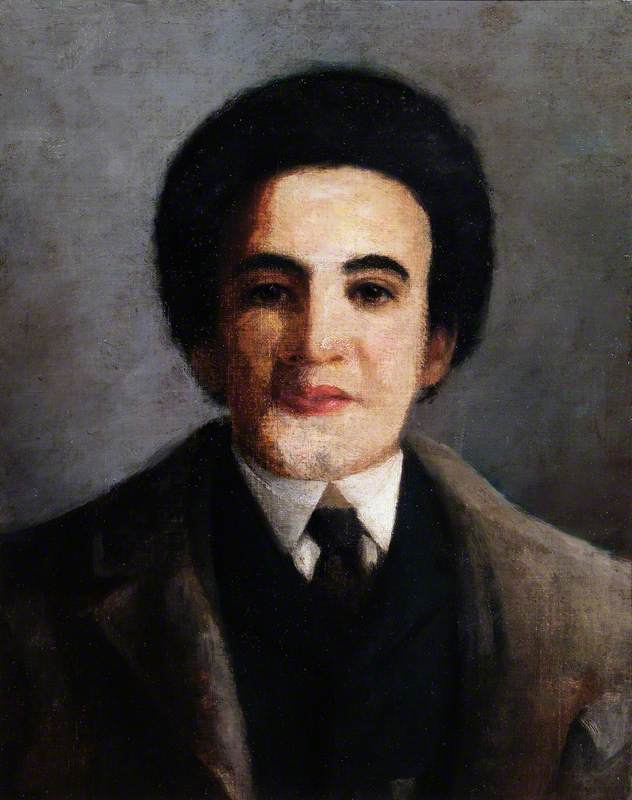

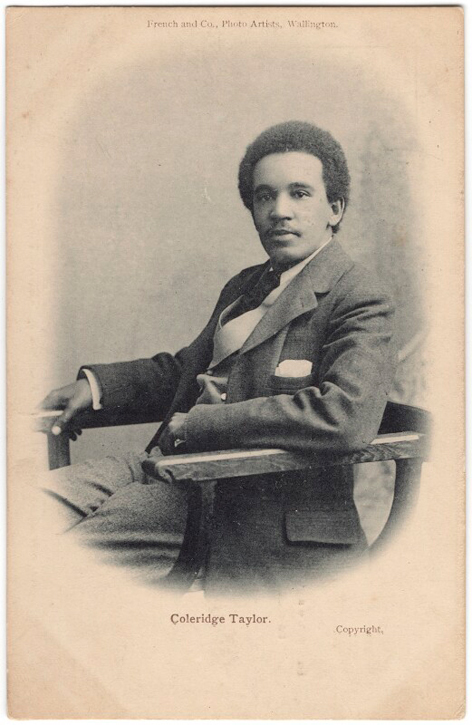

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

1901, photogravure postcard by Harry John Kempsell, for French and Co.

At the College, he was taught by Charles Villiers Stanford, who also taught the likes of Gustav Holst and Vaughan Williams. Stanford was amazed by Coleridge's talent, and after two years concentrating on the violin, encouraged the young man to study composition.

There is also anecdotal evidence that Stanford tried to shield Coleridge from some of the racism directed at him, often by fellow students.

Charles Villiers Stanford (1852–1924), Trinity College Organist and Composer

1920

William Orpen (1878–1931)

Composed in 1895, Coleridge's Clarinet Quintet in F sharp (Op.10) was his first success, delighting his teacher. He went on to further heights with his Ballade in A minor for orchestra (Op.33), which was performed in 1898 at the Three Choirs Festival. The more established composer Edward Elgar had recommended Coleridge as 'far and away the cleverest fellow going amongst the younger men.'

You can listen to the Chineke! Orchestra play the Ballade here:

Later that year Coleridge would write the piece most closely associated with him today. The composer had been inspired by The Song of Hiawatha – a poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow which concerns the titular Native American and his love, Minnehaha.

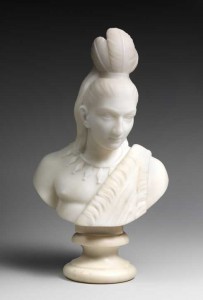

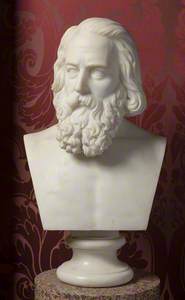

(Interestingly, Longfellow had been immortalised in sculpture by Edmonia Lewis, a Black American sculptor. Lewis also created a bust of Hiawatha, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.)

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807–1882)

1872

Edmonia Lewis

Coleridge began setting part of the epic to music, resulting in the 1898 piece Hiawatha's Wedding Feast. It was premiered in November of that year at the Royal College of Music, conducted by his teacher, Stanford.

After attending the premiere, Sir Arthur Sullivan (of Gilbert and Sullivan fame) wrote in his diary: 'Much impressed by the lad's genius. He is a composer, not a music-maker. The music is fresh and original – he has melody and harmony in abundance, and his scoring is brilliant and full of colour – at times luscious, rich and sensual. The work was very well done.'

Sir Hubert Parry (who later set William Blake's Jerusalem to music) described the event as 'one of the most remarkable events in modern English musical history.'

The composition was so successful that Coleridge wrote two sequels, based on other parts of Longfellow's work. The Death of Minnehaha premiered in October 1899 and Hiawatha's Departure in 1900. Together, all three are known today as The Song of Hiawatha.

You can listen to a recording of it here, conducted by Kenneth Alwyn, featuring the Welsh National Opera and Bryn Terfel:

The work continued to be popular well after Coleridge's death. Sir Malcolm Sargent (among others) conducted annual Hiawatha seasons at the Royal Albert Hall, which continued until 1939. These spectacular stagings involved hundreds of choristers, and scenery covering the organ. They must be seen in the context of the time, as the kind of cultural appropriation of Native American dress and customs that formed part of those performances would today be unacceptable.

It was around the time of Hiawatha's success that Coleridge-Taylor began to use the hyphenated version of his name, supposedly due to a publication error. His personal life was also busy around this time – he had married fellow student at the RCM, Jessie Walmisley, and they had two children: Hiawatha (yes, really!) and Gwendolen Avril (who would later compose under the name Avril Coleridge-Taylor).

In the first decade of the twentieth century, Coleridge-Taylor undertook three conducting tours of the USA, where he was feted as 'the Black Mahler'. Although today, labelling his works in relation to his ethnicity in such a way is problematic, it was no doubt understood as an accolade at the time.

During this time, he was celebrated in Washington and Baltimore with three-day festivals of his music. Unusually for a man of African descent, he was also received by President Theodore Roosevelt at the White House during his first visit in 1904.

But there was always the question of race and racism in America, and Coleridge-Taylor publicly demanded Black liberation, which would not have endeared him to large parts of the public. Despite this, his music was well received and – perhaps bizarrely – public schools were named after him in Louisville (in Kentucky) and Baltimore.

Back in 1897 he had befriended the poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, the son of an enslaved man, and this was to have an effect on his outlook. Dunbar suggested Coleridge-Taylor use African and African American songs and tunes in future compositions, and the composer also set some of his poems to music (African Romances, Op.17 in 1897).

Examples of Coleridge-Taylor's works being inspired by Africa included his African Suite, Op.35 of 1899 and his Symphonic Variations on an African Air, Op. 63 of 1906. In 1901 he also wrote a suite, Toussaint L'Ouverture, Op.46, which celebrated the leader of Haitian independence.

Another indicator of Coleridge-Taylor's increasing interest in his African heritage was that in 1900 he had been the youngest delegate at the First Pan-African Conference held in London – it was through this that he met African American scholar and activist W. E. B. Du Bois.

Coleridge-Taylor wrote opera, orchestral, church and chamber music, as well as incidental music for plays. He also worked as a conductor, beginning in the 1890s, when he conducted the Croydon Conservatoire orchestra – in 1904 he was appointed conductor of the Handel Society. That year saw him become Professor of Composition at Trinity College of Music.

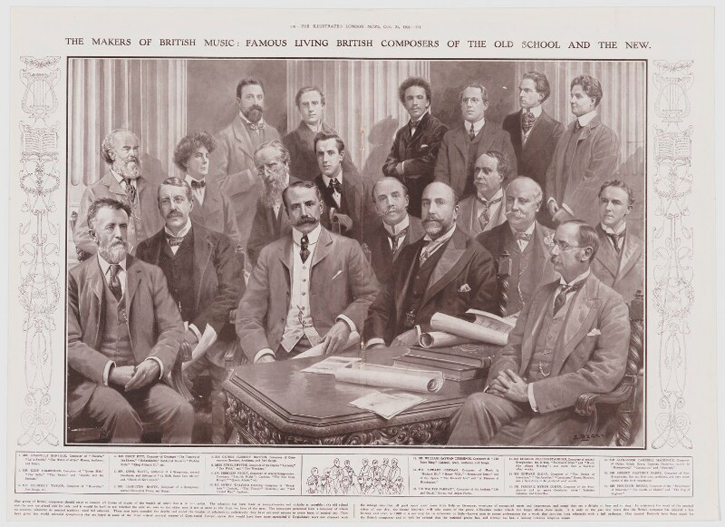

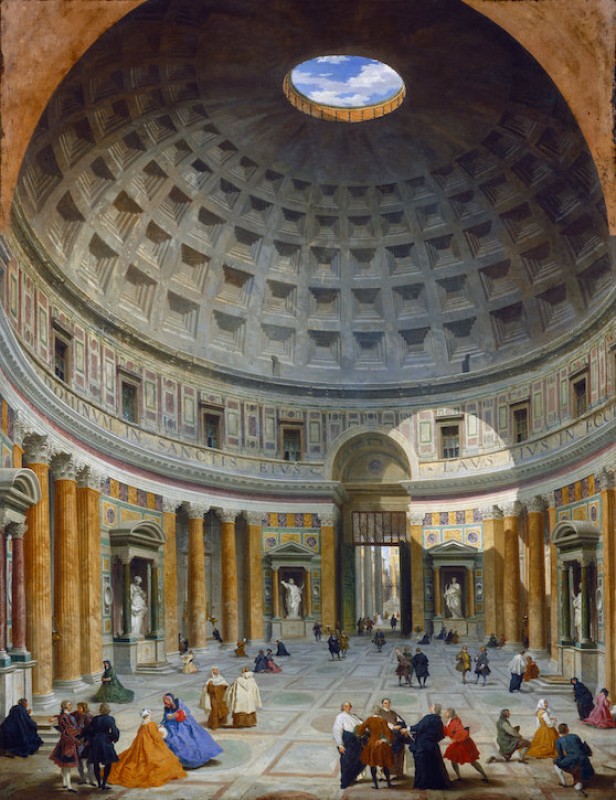

He was largely accepted by the musical establishment of his day – his undeniable talent shone through any clouds of racism directed towards his music. This fascinating image from 1908 shows British composers old and new – it includes many 'big names' such as Elgar, Parry, Bantock and Stanford. There's also Ethel Smyth on the left (the only woman in the image).

Coleridge-Taylor cuts a dashing figure in the middle, seemingly ready to take on the world. However, his untimely death just a few short years later, at the age of 37, robbed the world of what might have been.

In August 1912 he collapsed at West Croydon station while waiting for a train, but managed to make it home. He was to die a few days later from pneumonia, on 1st September.

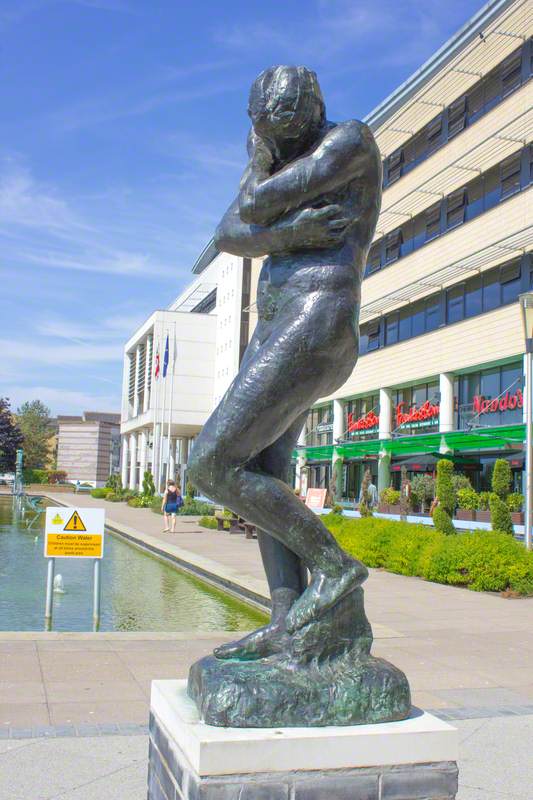

Hundreds of people turned out for his funeral. He is still remembered in his home town of Croydon fondly – in 2013, when the public voted for famous residents to be immortalised in sculpture, he won the vote alongside comedian Ronnie Corbett and actress Dame Peggy Ashcroft.

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor's music will no doubt live on as it contains an irresistible mix of melody, harmony and a broad outlook on the world – one that stands in contrast to the nationalism that dominated classical music at the turn of the twentieth century.

There has been a resurgence of interest in his works in recent years, with new discoveries of manuscripts and unpublished works. Hopefully more recordings and performances will find their way to new ears and the world will once again recognise the genius of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor.

Andrew Shore, Head of Content at Art UK

Further reading

Jeffrey Green, Coleridge-Taylor: A Centenary Celebration, History and Social Action Publications, 2012

Jeffrey Green, 'Samuel Coleridge-Taylor: Composer'

Jeffrey Green, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, a Musical Life, Pickering and Chatto, 2011

Percy M. Young, 'Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, 1875–1912' in The Musical Times, Vol. 116, No. 1590, August 1975, p.703–705