You may have read our spooky story about the nation's scariest art. Just in time for Halloween, creepy art returns with a vengeance and is scarier than ever, in our horrifying sequel...

Art UK's editorial team have spent weeks processing thousands of new artwork records from the Wellcome Collection – objects owned by the important biomedical research charity. The additions of drawings, watercolours and prints will make the collection one of the largest on Art UK. It's an unusual group of works, connecting medicine, science, art and life.

Its founder, Sir Henry Solomon Wellcome, had an eye for the unusual, and an insatiable curiosity about the world around him. Through the images and objects he collected, we can learn about the past – what people feared, what they desired, and what they understood about the human body and the world around them.

The world probably felt even more mysterious and unpredictable than it does now. If you made it to adulthood, commonplace diseases and accidents could kill off even the healthiest of citizens.

So let us take you on a harrowing trip through the Wellcome Collection. It will spook you into being grateful that you were born within the last hundred years. Although intriguing and sometimes even beautiful, the images found within paint a terrifying picture of the past.

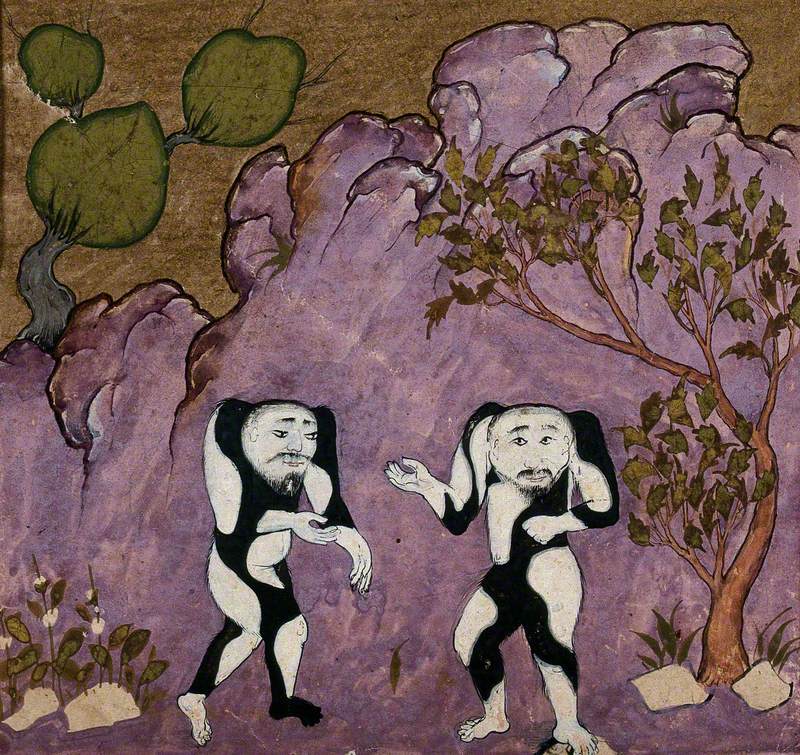

Fear of the unknown

Imagine a time when monsters rampaged with impunity, and corners of the globe were yet unknown to the western world – likely filled with strange beasts, such as this fantastic pair. To western eyes, the world was a large and mainly unexplored place. Humans were yet to map out the planet, and also yet to gain knowledge of many things we take for granted, in the realms of chemistry, physics and biology and medicine.

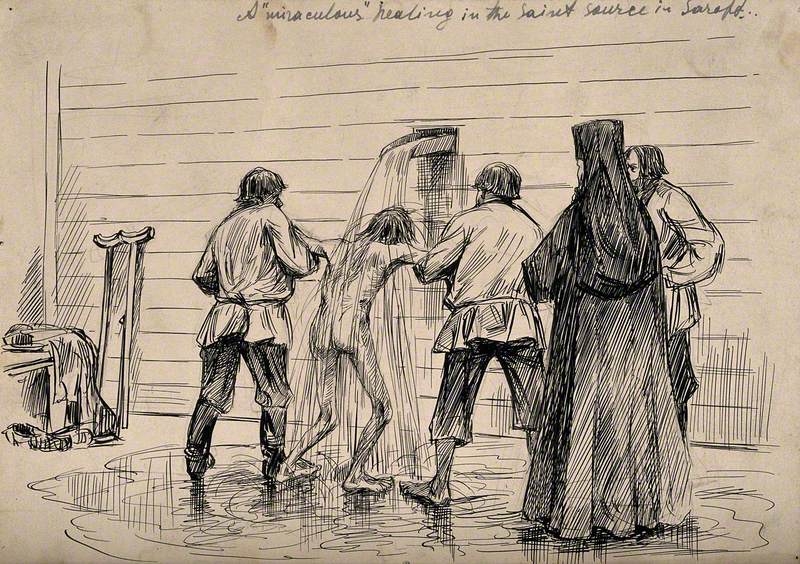

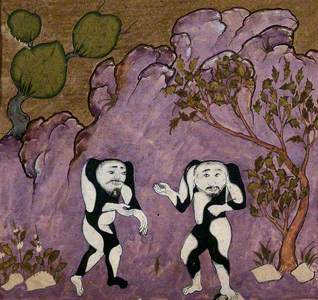

'Insanity' could be 'cured' by expelling devils, and being guided naked into a cold spring could be on the cards for any Russians experiencing a crippling disease.

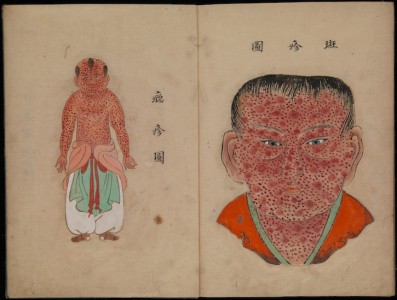

Disease and pestilence

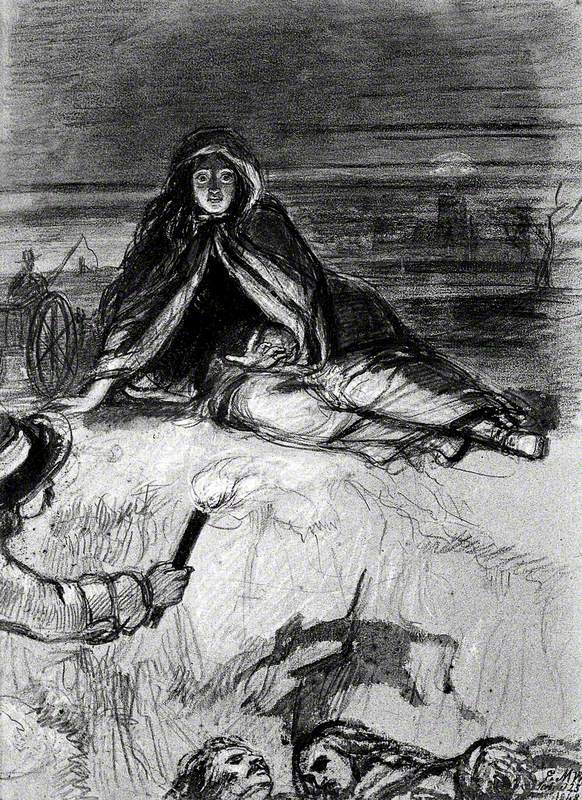

Among the many challenges of modern life, thankfully widespread bubonic plague – the Black Death – isn't one of them.

A Woman Seated on the Ground, Torchbearer to Left, below Heads of Plague Victims

Edward Matthew Ward (1816–1879)

The pandemic devastated human populations in the fourteenth century and had a staggering social impact – as illustrated by Victorian narrative artist Edward Matthew Ward.

A Terrified Man Realising He Has Just Contracted the Plague, Surrounded by a Group of People

Edward Matthew Ward (1816–1879)

The rather comical expression of A Terrified Man... doesn't quite have the same impact as A Woman Seated on the Ground... but the prognosis of someone with the plague – enlarged, infected lymph nodes, decomposition of the skin, and a painful death – is no laughing matter.

Working a little later than Ward, the relatively obscure artist Richard Tennant Cooper has a great many works in the Wellcome Collection illustrating various diseases and their effects in a nightmarish style.

In the early twentieth century diseases were still feared and misunderstood – and with two World Wars raging in the background, their effects unpredictable and scarier still.

A Ghostly Skeleton Trying to Strangle a Sick Child; Representing Diphtheria

Richard Tennant Cooper (1885–1957)

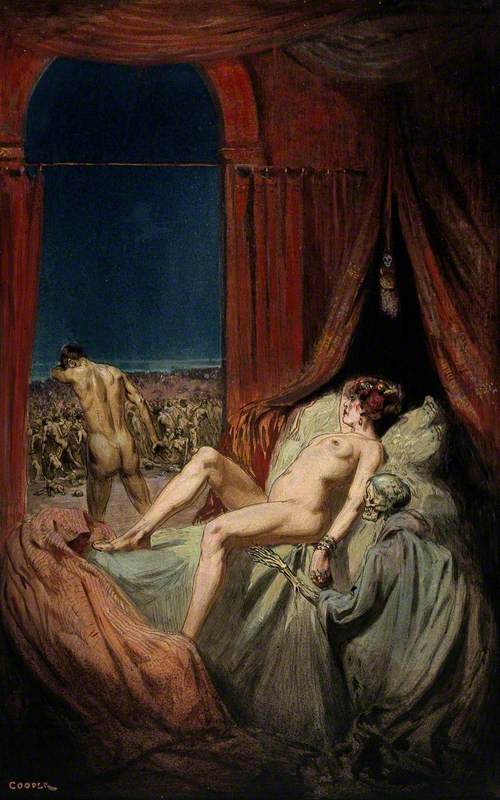

Tennant Cooper's works present diseases as nightmares that can attack anyone, from the young innocent to the 'provocative' young women depicted in his portraits of syphilis – horrifying not only because of the hideous disease they depict, but also due to the starkly unfair attitudes toward women. The venereal disease is represented as lurking behind seductive young women; the men shown as hapless victims in their wake.

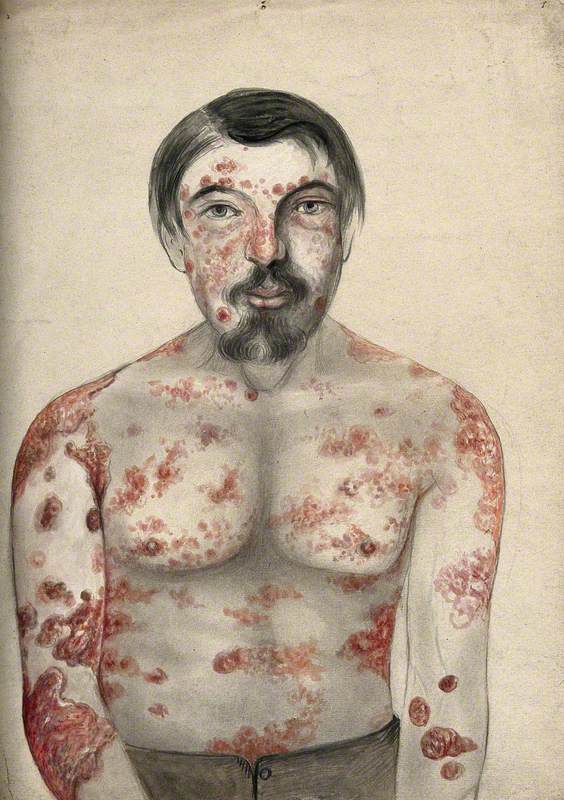

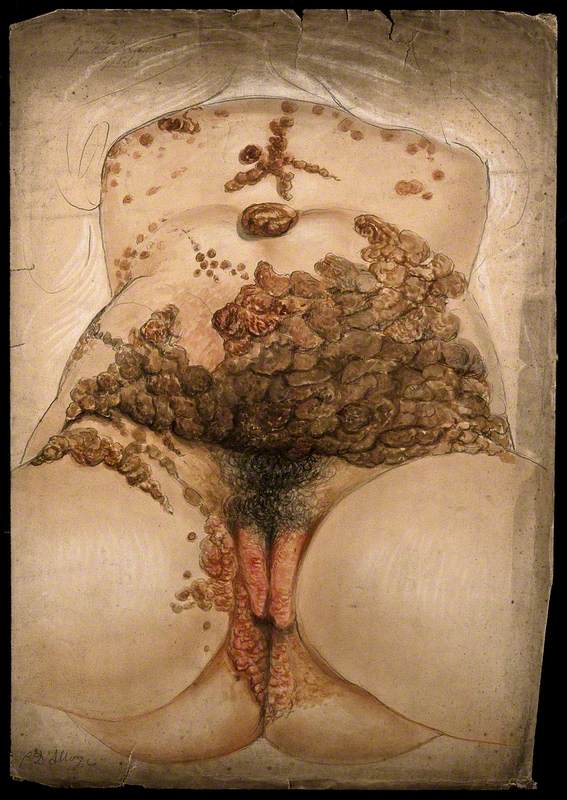

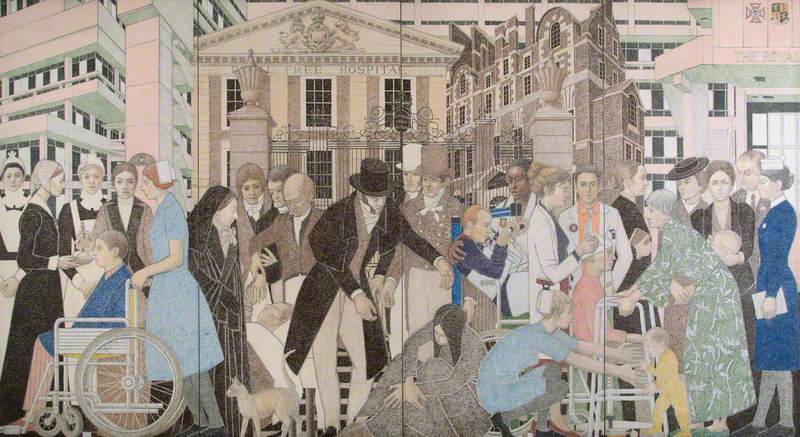

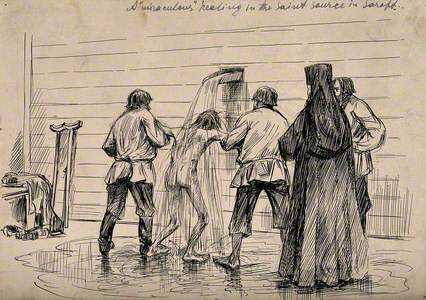

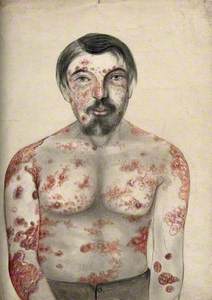

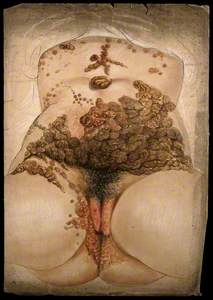

The effects of syphilis are rampant in the work of Christopher d'Alton, the Wellcome's unofficial king of disease pictures. His flat, uniform sketches are perhaps the most disturbing anatomical images to confront viewers of this collection, due to their objectivity and bleak realism. D'Alton was a hospital artist, depicting patients in the 1850s and 1860s at the Royal Free in London.

Looking through the rest of his art (NSFW – unless you work at Art UK) is a strange experience, not for the overly squeamish. Once you get over the uncomfortable feeling of staring directly into the lower orifices of a sickly man or woman, in brutal close-up, it's interesting to think about the detail D'Alton put into these works, and imagine how uncomfortable it might have been for him to make these extraordinarily detailed images – not to mention how uncomfortable life must have been for many of the afflicted, trying to go about their daily lives with these repellent symptoms.

In the nineteenth century, were sores, pustules and deformities simply a common sight? The fact that these portraits were made indicates that afflictions were unusual, or perhaps at least the more severe examples of common issues.

A Young Man, J. Kay, Afflicted with a Rodent Disease which Has Eaten Away Part of His Face

c.1820

unknown artist

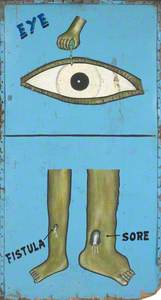

The matter-of-factness and clarity of these portraits indicate that the works were perhaps used as a learning aid, in order to advance medical knowledge. The series including A Young Man, J. Kay... shows further afflicted residents of Leeds, yet luckily for Mrs Bennett, the successful story of her recovery was also recorded.

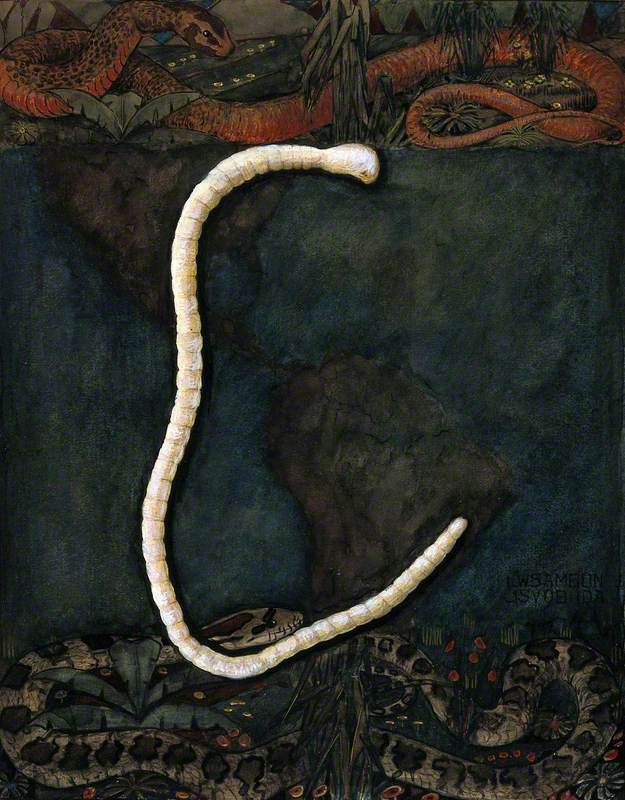

Also worth a mention are the darkly beautiful yet haunting images of various parasites by J. Svoboda – eyeless pale worms lurking in soil, unseen by the unsuspecting animal 'hosts' painted in the surrounding image.

Parasites: A Parasitical Worm, Shown Much Enlarged, with Its Hosts

(after Louis Westerna Sambon)

J. Svoboda

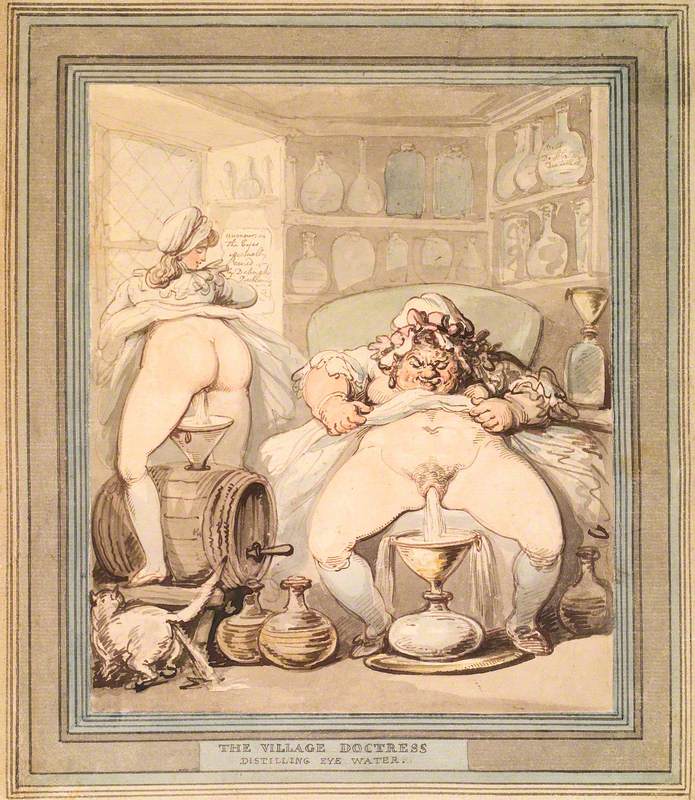

The cure is worse than the disease!

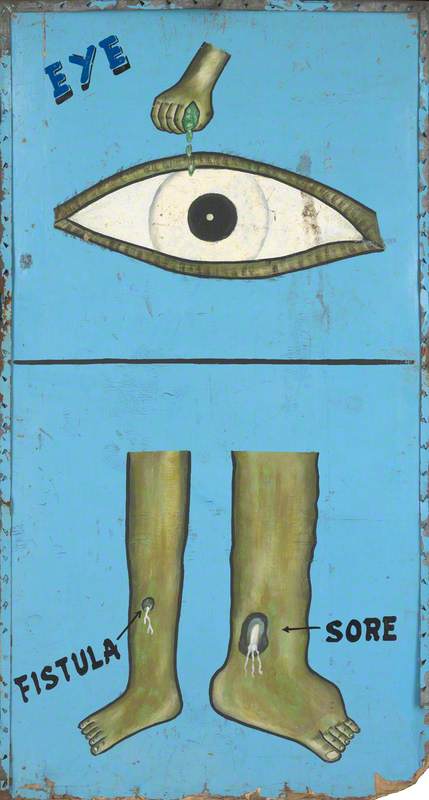

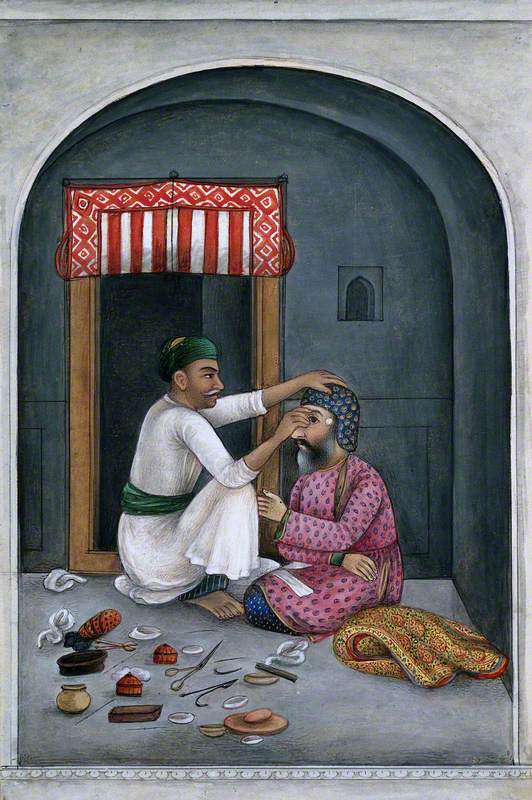

With hindsight, we can see the steady progress of medical knowledge and treatments depicted in works at the Wellcome Collection. It's clear we've come a long way from the days of surgical eye tools left on the floor, and blacksmiths stepping in to perform dentistry.

A Physician Wearing a Seventeenth-Century Plague Preventive Costume

c.1910

unknown artist

This striking painting shows a physician as described by Jean Jacques Manget in Geneva in 1721. We can see how covering the eyes (with glass), nose and mouth, while wearing thick, all-covering leather as a protective measure, makes a good deal of sense, even without today's awareness of the importance of sterilisation.

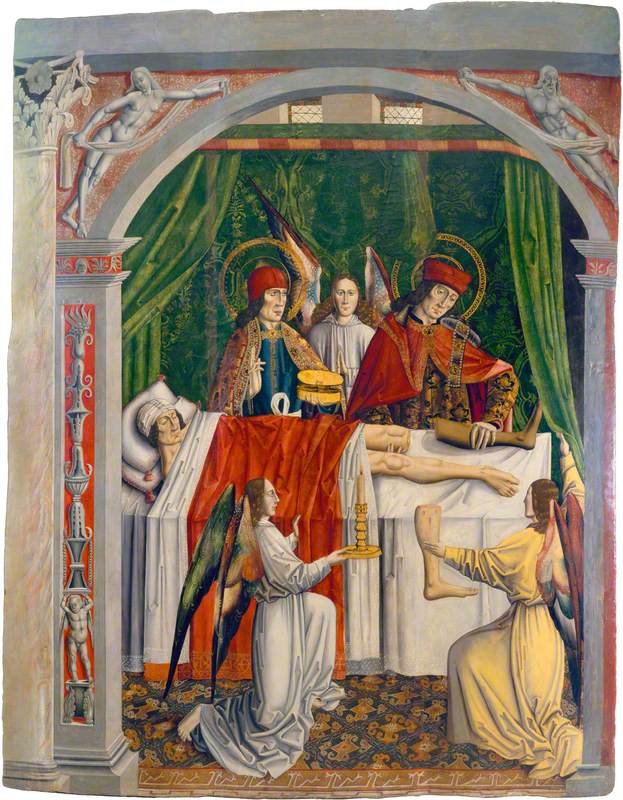

Medical interventions are approached with the spirit of venturing into the unknown – and with it, an awareness that treatment was a privilege and not a right. Quacks and cowboys took advantage of the general mystery of medical matters, and ultimately made their living from death and disease.

An interesting 1950s piece by Dorothy Mary Barber documents a change in attitudes, toward a more holistic approach. Commissioned by a consultant physician, it was created to illustrate to medical students the importance of the social background of a patient.

Apparently, Barber painted the scene from the window, put off from entering due to the smell emanating from the room, with its peeling wallpaper and bucket by the side of the bed. The man, living in Harlesden, suffered from bronchitis and arthritis.

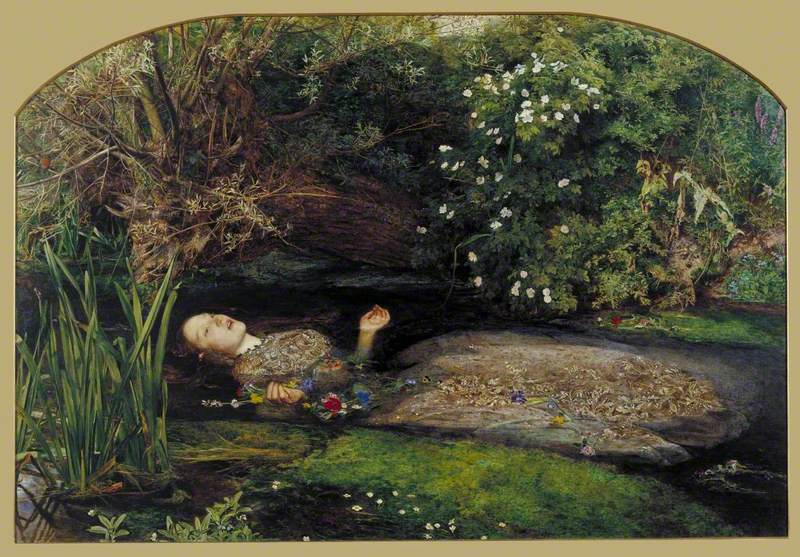

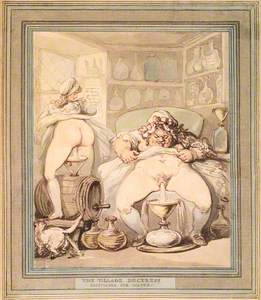

Sometimes it's hard to be a woman...

Being a woman is tough, and was especially in the days before widespread birth control, and advances in gynaecology and obstetrics.

Presumably, the tiny baby visible in the urine of this pregnant woman was a visual metaphor (one would hope?), but the distress of an unwanted pregnancy is a relatable topic today – as is the diminished responsibility of the presumed father, peeking from behind the door.

It can be an infuriating experience to look at historical depictions of women's medicine. In the two examples above, made approximately a century apart, the mothers are shown to have little privacy; vulnerable and exhausted in a whirlwind of activity.

Strangely, the acquisition of the older of the two works is described as a hasty tradeoff between men in the street, before it eventually made its way into the hands of Sir Henry Wellcome. Were the male traders of the unusual painting interested in the work for its medical value, or its full-frontal nudity?

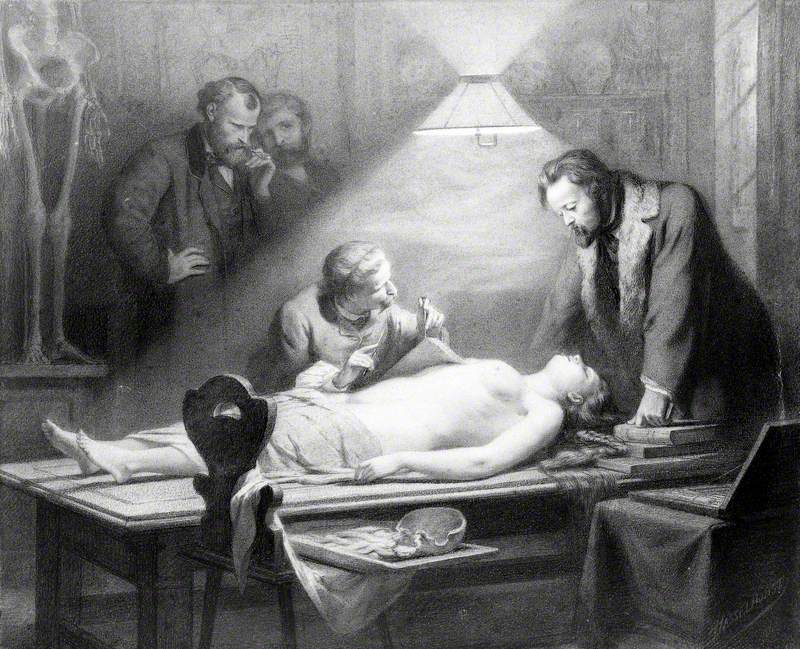

This study documents the real-life autopsy of the cadaver of a teenager who died from suicide. The body was 'selected for its attractive proportions, in order to determine the ideal measurements of the female body'.

Uncomfortable to look at today, the male artists and anatomists stand smoking cigars and staring at the nude body of the woman. With her long hair and protruding breasts, glowing in the downcast light, her passive body's sexualisation is integral to the composition.

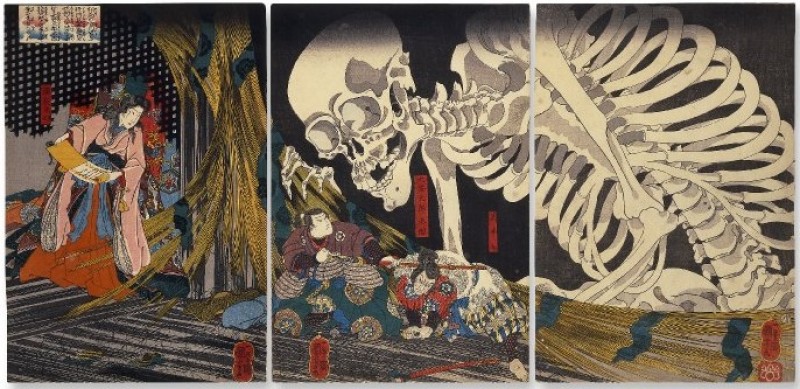

Dancing with death

Death stalks the Wellcome Collection, where you'll find many a dancing skeleton or cloaked figure. In the previous centuries, experiencing a person's death was simply more common – at home or in public.

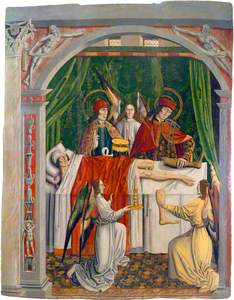

A Man Praying to the Virgin and a Monastic Saint to Save a Child Trapped beneath a Drain-Grid

1727

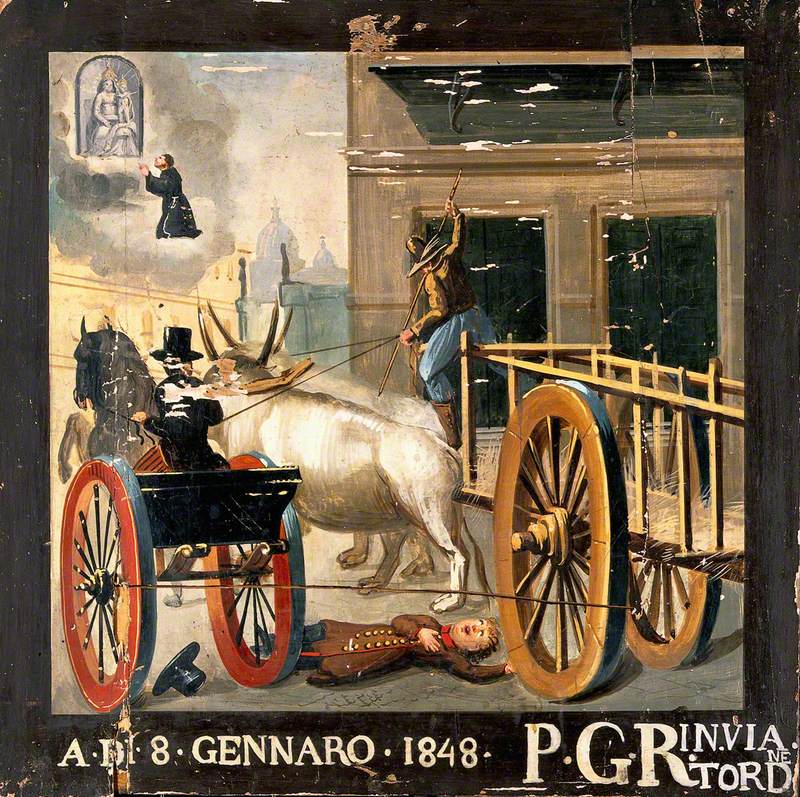

Italian School

The streets were dangerous, not just because of disease but also a lack of safety standards. This seems like something very trivial, but it is easy to take for granted that children can now navigate the streets without falling down a loose drain or being squashed by a passing ox cart. The Wellcome Collection is full of fascinating votive art, made as an offering of thanks – usually for surviving an illness or accident.

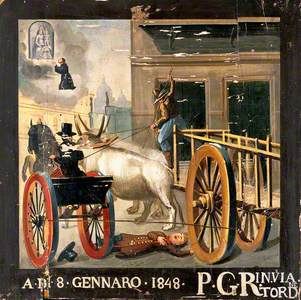

A Man Praying to the Madonna del Parto for a Child Run Over by an Ox Cart

1848

unknown artist

Crime and punishment

In this horrific votive scene, a man attacks a woman with a stiletto dagger while her child looks on. Wellcome's description indicates the painting was made to fulfil a vow to the Madonna del Parto, to whom the woman is appealing in the picture. 'The existence of the painting is evidence that she did recover from the attack, or that her attacker stayed his hand as a result of her appeal to the Virgin.'

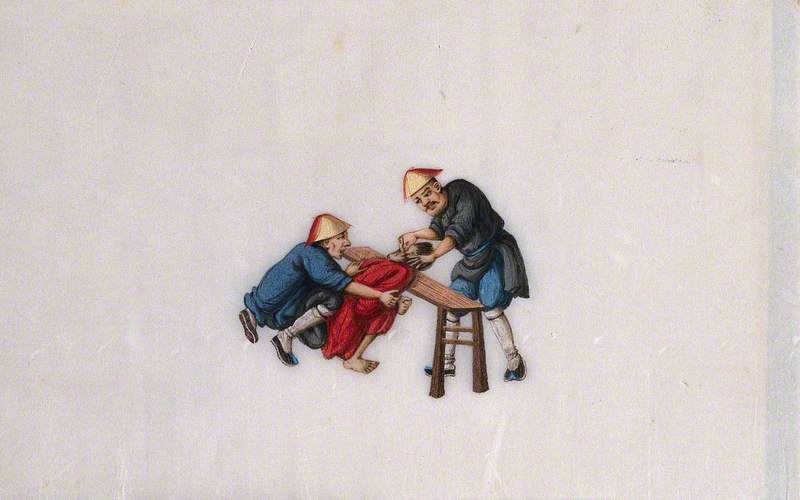

You would hope that the male attacker would face the consequences of his actions, though until recently corporal, or physical, punishments were in place for falling foul of the law – and, in some cultures, are still in place today. Sir Henry Wellcome's collection includes some sketches of Chinese prisoners undergoing variously hideous forms of torture in the mid-nineteenth century.

A Chinese Torturer Pushes a Sharp Instrument into the Eardrum of a Prisoner

c.1850

unknown artist

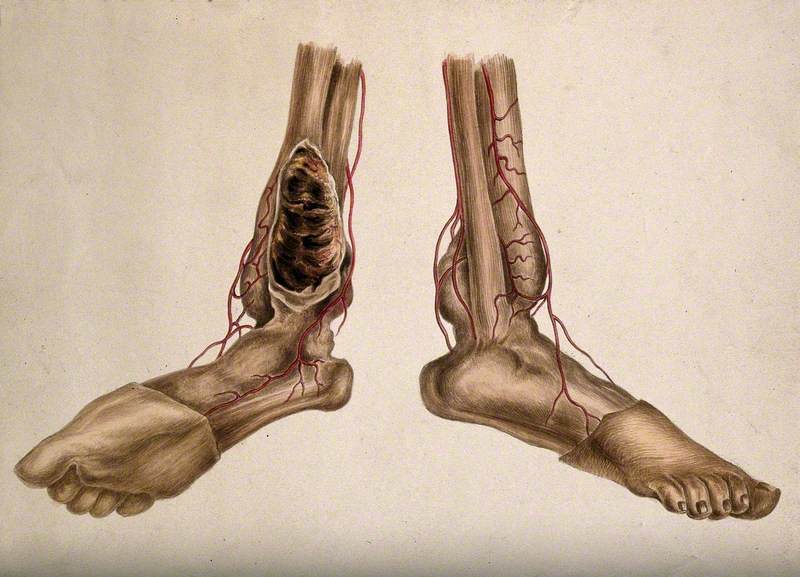

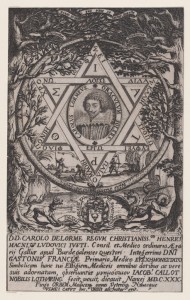

Art and anatomy

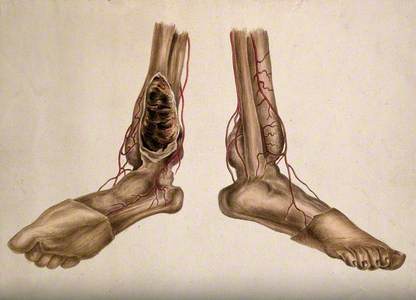

Ironically, without the rampant death and destruction of the past, we wouldn't have the knowledge that has enabled society to lower the mortality rate in present times. Examining dead bodies through anatomical study paved the way for modern medicine.

During the Scientific Revolution of the nineteenth century, scientists were hungry for fresh cadavers, sparking accusations of anatomy murder and body snatching – William Hunter, along with William Smellie, was accused in a (non-peer reviewed) article in 2010 of using the bodies of murdered pregnant women to advance their studies. Medical historians have argued this has no founding in truth. Yet the Burke and Hare murders in 1828 proved that the citizens of Edinburgh of that time were not safe from being murdered and sold to an anatomist.

These gruesome incidents, however, do not negate the worth of anatomy studies, and Wellcome Collection has some incredibly beautiful examples of the genre. Looking through the collection has taught me that it is worth facing your fears and braving its chilling contents – there's plenty to dissect.

Jade King, Head of Editorial at Art UK